» Transforming Hampstead Village by Mateo Mérida

As Charleston has become one of the fastest growing cities in the US, few areas have seen as much change as that of Hampstead Village. While many people chose to call Hampstead Village home today, that was not a luxury that was afforded to its residents over a century ago. In the time since, Hampstead Village, commonly known as the Eastside, has become one of the most important districts of the city. For generations, the Eastside has been emblematic of a proud, but self-sufficient, community of Black Charlestonians despite its larger position in an environment of white supremacy.

Named after a suburban district near London, Hampstead Village was initially founded to be a suburb of Charleston during the colonial era. It was effectively removed from the map during the War of Independence, and was then restored to become a bustling, multi-ethnic working-class neighborhood through the Antebellum period. By the turn of the twentieth century Hampstead Village had become the home of affluent white Charlestonians and a major neighborhood in the city of Charleston. Within about 50 years, Hampstead Village would come to be known generally as the “Eastside.” As the result of suburbanization, redlining, and Jim Crow, white Charlestonians began to relocate from urban areas like Hampstead Village to growing suburban districts, such as West Ashley and Mount Pleasant. As wealthy whites left Hampstead, poor black families were relegated to the Eastside.1

The name Eastside has become so synonymous with Hampstead Village, that the name “Hampstead” has been totally alienated from the neighborhood it referred to. In an interview with longtime Eastside resident Martha Sass, the interviewer asks about the commonality of the name “Hampstead.” Sass emphatically describes “I’ve never heard of Hampstead. We’ve always referred to it as the East Side, and everybody – I grew up on the East Side, that’s what I tell everybody. I’m from downtown Charleston on the East Side, and everybody that grew up in the area, especially the East Side, the West Side, they know what you were talking about.”2This interaction illuminates that while Hampstead was initially organized to shelter privileged white Charlestonians, its eventual abandonment by those occupants led to the reinvention of Hampstead into the Eastside; a community for underserved Black Charlestonians.

Black artisans on the Eastside helped create a community they could be proud of. On Blake Street is Phillip Simmons’ home and workshop. For the better part of a century, Simmons was one of the most celebrated blacksmiths in the world, making iron rails, gates, and fences for countless homes and businesses across the Charleston area. Simmons was a beloved member of the Eastside community, opening his home to school groups, gifting money to young high school graduates, and avidly participating in his church.3

While excellent artisans helped to define the Eastside community, so did other forms of labor, which have been taken for granted historically by Charleston. Just north of Simmons’ workshop stands the Cigar Factory, one of the most prominent landmarks of the city of Charleston, which employed as many as 2000 Black and white men and women after World War II. Similarly, many Eastside men would have worked on the many docks near East Bay Street, while many women would have commuted to the opposite side of the peninsula to work at the hospital at MUSC, one mile away.

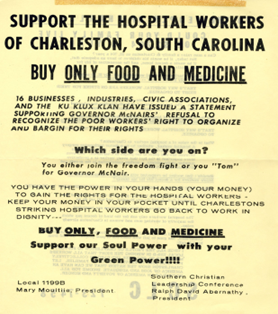

The Eastside was a hotbed of labor activism. The Cigar Factory in 1946 and the hospital at the medical college in 1969 were both the sites of major labor strikes organized by the Black workers. These strikes became high profile events in the city’s history, and that is due in no small part to the role Eastsiders played in supporting their fellow community members. During the hospital strike which started on March 17, 1969, several organizations reached out in support of the hospital, who underpaid Black employees and reinforced unfair discriminatory practices. During the strike, the organizers requested members of the community boycott products from these companies. By June 27th the same year, the hospital agreed to end these discriminatory practices and offer incremental pay increases to the workers. The strike on its own would not have been successful without the work done by Black Charlestonian community members, like those on the Eastside who applied pressure to the hospital, and its supporters. In this way, the Eastside was a community of solidarity, helping to create important advances for its residences.

Even young members of the Eastside community were ready to be a part of the action for the hospital strikers. Timothy Grant was a teenager raised on the Eastside at the time of the strike, and vividly remembers a moment when the protest turned violent. Some of the protesting nurses found themselves in a heated argument with a police officer who pulled out a baton and began to swing at them. Grant and his friends stepped forward, and “went to battle” with the police officers. They were subsequently arrested and Grant recalls that he was more than happy to have spent the night in jail, because he had come to the protest to begin with to protect the striking sisters and mothers of the Eastside community.4For the Eastside, a sense of social responsibility was instilled at a young age.

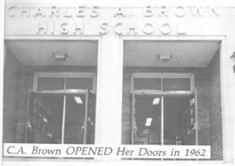

Community was also represented in the institutions that Eastsiders organized themselves. For many years, Burke High School was the only public high school for Black students in Charleston. As it continued to become increasingly overcrowded, Eastside High School was founded in 1962, before changing its name to Charles Arthur Brown High School (named for a trustee of the Charleston County School Board) later that same year.5 C. A. Brown became synonymous with the community it was situated in, which is reflected by the school mascot, the Black Panthers in 1966. As a nod to the radical Black organization founded in Oakland, California, selecting Black Panthers as the school mascot reflected a strive for excellence, a militancy and self-determination among its students, as well as pride in their heritage as African American students and educators.

However, C. A. Brown did not become notable because of its mascot, but rather because of what it gave to the Eastside. Students who were enrolled there enjoyed substantive job training, summer schooling, as well as remediation courses to improve student literacy. They also participated in the arts, organizing musical and theater performances, as well as sidewalk art shows. In this way C. A. Brown provided recreational activity through participation and viewership, as well as a component of aesthetic beauty to Eastside’s public spaces. C. A. Brown’s biggest contribution, however, may have been the way it impacted older members of the Eastside community. Many Eastside parents at one time, due to circumstance, poverty, or family emergencies, were unable to finish school. To combat this, C. A. Brown offered a high school equivalency program, which provided many the ability to complete their education.6

Relationships between the Eastside and their neighbors have always been reliably tight, even for new members. Mary Edwards spent her early childhood in the Ansonborough neighborhood until her parents passed away, and she moved in with her uncle who lived in Eastside in the 1950s. She remembers “The neighborhood was very close. You knew everybody, you know, all the children. I think on our block, there probably was at least twenty-five plus children, and just in a few houses, people had big families.”7 To get to know each of the children was to get to know each of the families.

The Eastside is a space that Black people have made their own and established profound networks of support that many other neighborhoods do not necessarily share in common. These connections extended well beyond simple familiarity, as it also became a mechanism of support. The old saying “it takes a village to raise a child” was especially true for Hampstead, as children who grew up in the neighborhood would be supervised by community members. Edward Jones, born and raised in the Eastside, came up in a single mother household. When he and children in similar household structures were ready to play in the neighborhood, the “village” kept an eye on the children to ensure their safety. When single Eastside mothers could not supervise the activities of their children, they could count on the Eastside as a community to be that support.8

In a lot of ways, the Eastside developed such a deep connection as a community largely because they didn’t have a choice. The Eastside, and communities like it, developed specifically because of the anti-Black racism of Jim Crow apartheid. However, while these policies existed to oppress, that does not mean that is all these community members felt. Herbert Frazier was a teacher at C. A. Brown but was raised in Ansonborough. He explains “…you never really felt as though your life was missing anything as a result of the absence of white people in your classroom or your church or your neighborhood. Because back in those days, and although people think that we were poor, we were rather rich in a number of ways because we had families, we had strong teachers, caring teachers.”9Black Charlestonians—whether in the Eastside or Ansonborough—did not collectively choose to live in the Eastside. Despite this, the Eastside became a vibrant, supportive, and inclusive community by choice.

In recent years, gentrification has posed a major threat to Eastside residents. While it was considered undesirable by privileged people in the past, it is a magnet for people looking to relocate in Charleston in no small part because of its relatively cheap property value. As predatory development corporations zero in on houses that have been owned by Black families for decades and seek to destroy longstanding businesses and replace them with trendier shops, the Eastside community is under threat of destruction. As Charleston continues to grow and evolve, communities like the Eastside need to be protected as the cultural gems that make the city of Charleston so unique. In the same way that Black Hampstead Villagers chose to transform the Eastside and we should all choose to celebrate and protect its legacy as a haven for Black Charlestonians.

Sources

- Nic Butler. “Hampstead Village: The Historic Heart of Charleston’s East Side,” Charleston Time Machine, ep. 131 (Oct. 18, 2019), Accessed May 2, 2023, https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/hampstead-village-historic-heart-charlestons-east-side.

- Katherine Pemberton, “Oral history interview with Martha Sass,” Oral History Project, (Historic Charleston Foundation: Charleston, SC), 2017, pp. 4, accessed May. 2, 2023, https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/246471.

- “Keeper of the Gate: Philip Simmons Ironwork in Charleston, South Carolina,” Lowcountry Digital History Initiative, May, 2014, accessed May 2, 2023, https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/philip_simmons/documentary_tribute.

- Kieran Taylor, “Timothy Grant, Interview by Kieran W. Taylor,” The Charleston Oral History Program (Charleston, SC: The Citadel Archives & Museum) June 24, 2009, pp. 36, accessed May 2, 2023, https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/269242.

- “Our School,” Charles A. Brown High Alumni Association, accessed May 2, 2023, https://cabhaa.wordpress.com/history/.

- Ibid.

- Courtney Akana, “Mary Edwards, Interview by Courntney Akana,” The Charleston Oral History Program (Charleston, SC: The Citadel Archives & Museum), March 9, 2015, pp 2, accessed May 2, 2023 https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/261084

- Emile Charles, “Oral History Interview with Edward Jones,” Oral History Project, (Historic Charleston Foundation: Charleston, SC), 2021, pp. 2, accessed May 2, 2023 https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/251737.

- Courtney Akana, “Herbert Frazier, Interview by Courtney Akana,” The Charleston Oral History Program (Charleston, SC: The Citadel Archives & Museum), Mar. 18, 2015, pp. 3, accessed May 2, 2023 https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/261083.

Image Credit

- “Group of People Standing, Sitting Outdoors.” 1969. Charleston, SC. Courtesy of Avery Research Center. Accessed May 2, 2023, https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:93259.

- A poster to convince viewers to participate in boycotting businesses crossing the hospital strike picket line. 1969. Charleston, SC. Lowcountry Digital History Initiative. Courtesy of Avery Research Center. Accessed May 2, 2023, https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/charleston_hospital_workers_mo/coretta_scott_king_visits_char.

- Image showing the front of Charles A. Brown High School. C. 1960s-1970s. Charleston, SC. Courtesy of the Charles A. Brown High Alumni Association. https://cabhaa.wordpress.com/history/.

- Image of cigar factory and the Eastside from the view of the Cooper River Bridge. David Chamberlain. 1980. Charleston, SC. Courtesy of The Charleston Archives of the Charleston County Public Library. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:6004.