» The Story of an African American Settlement Community: Maryville, SC by Mateo Mérida

John Wright is a Black man born and raised in Mount Pleasant, SC, who served in the navy, and returned home shocked to find how much his hometown had grown, and changed. Some of these changes were somewhat superficial, such as new stores, new restaurants, and getting to the rural parts of town didn’t used to take as long as it does now. But behind all of that came several racially charged and demographic changes. He describes “Mount Pleasant, when I left home, we were about 22% black or about 22% of the population, and when I came home, we’re less than 5%.”1 In all of the rapid growth that Mount Pleasant has seen in recent years, this phenomenon of displacing Black communities is far from a new one.

The Charleston from 100 years ago was very different from the Charleston of today. Several of the places that are considered smaller epicenters removed from downtown Charleston, like James Island, Daniel’s Island, and West Ashley, were once several small towns now called African American Historical Settlement Communities. Legally, these communities have been called ‘unincorporated’ or ‘donut hole’ communities. For John Wright, referring to them as settlement communities better reflects the historical significance that these places have held on Black history. He elaborates that “these people settled after Reconstruction and bought the land–not given the land, but bought the land.”2

In the immediate aftermath following the Civil War, efforts were made to integrate the once enslaved population into mainstream Southern society. One of the responses to this was in the dissolution of plantations and posting them for sale for Black families to purchase. Meanwhile, with apartheid Jim Crow laws slowly taking form throughout the Southeast, Black Americans coming together to create these new communities sought to create safety, security, and structure for their families, in an increasingly hostile anti-Black environment outside of these communities.

In the heart of today’s West Ashley, where a Walgreens sits at the divergence of St. Andrew’s Boulevard and Ashley River Road, the area surrounding was once home to one such of these communities, which happened to be one of the most prominent African American Settlement Communities in the Lowcountry. Prior to the displacement of Cusabo people, the land was delegated by the British Crown to the Lords Proprietors,3 who would pass the land down generation after generation. Ultimately, this land would come to be known as the Hillsborough Plantation.4 With Hillsborough’s dissolution, several Black families bought up some of the land, and founded a small town in 1886, which would be called Maryville, named after Mary Just, who was a teacher, and prominent local figure in the early establishment of the community.

The heart and soul of Maryville was the Emanuel A.M.E. Church, which still stands in West Ashley today (not to be mistaken with the Mother Emanuel AME Church in downtown Charleston). Every Sunday, Maryville’s population would pray, and then spend the day socializing with everyone else in the community. Much of Maryville’s population were small-scale farmers, growing enough food to provide for themselves, and to sell to other residents of Maryville and other nearby communities. Some, such as Mary Just, were teachers, others were shopkeepers, undertakers, or part of local government.

The woman in this image is Miriam DeCosta Seabrook, who was a resident of the Maryville community. Small houses like the one shown here were prevalent throughout the small town, and many of them still stand there to this day as a memory of the Black families who lived and sustained a vibrant community well before it became the West Ashley we know today.

Despite the crucial role that Maryville held for the self-determination of South Carolina’s African American population, it was explicitly seen as a threat by the surrounding white community. One white legislator of the time wrote “In regards to charter of Maryville, SC, this town as you know is an incorporated town and run by Negroes: being an incorporated town the county police have no right in there, therefore the white residents are at the mercy of these Negroes.”5 Ideas like this that presented Maryville as a sort of haven for criminals as well as an existential threat to the surrounding white population led to the revoking of the charter in 1936, and its later annexation by the city of Charleston.

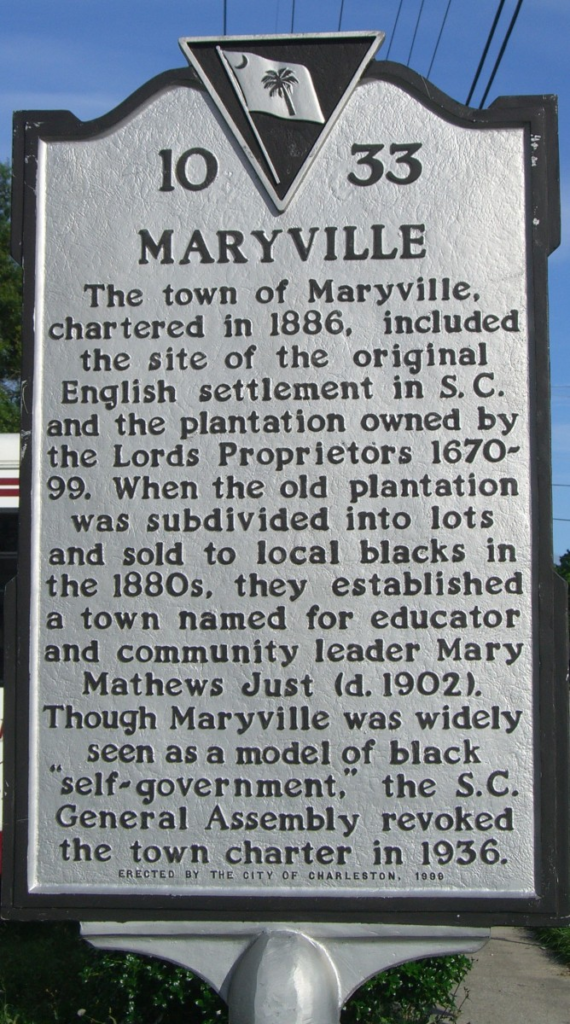

However, its memory has not been lost to the rapid development of the area. In 1999, a historical marker was placed just outside of Emanuel AME, which commemorates Maryville’s history. Similarly, in June 2021, Charleston educator Diane Hamilton published Maryville, The Audacity of a People, which shares much of her own research and findings about what Maryville once was. There are also several Black families who still live in Maryville that have deep roots in the community.

Maryville serves as an example of an African American Settlement Community that has been encroached upon, or otherwise challenged by, gentrification, targeted legislation, and land development. In 2019, Black people made up 22% of Charleston’s population6, which was almost cut in half from 41% of Charleston’s population in 1990.7 Similarly, in 2000, 38% of the population living in Charleston moved there from out-of-state (like myself), and that number climbed to 44% in 2013.8 As Charleston continues to expand beyond the confines of the peninsula, erasure of many communities like Maryville and the once-rural exterior of Mount Pleasant is only a matter of how, not when.

Sources

- Wright, John interviewed by Timothy S. Pierre. “Oral History of John Wright, interviewed by Timothy S. Pierre., 14 April 2021.” The Citadel Archives and Museum: Oral Histories, 2021. Pp 10. https://citadeldigitalarchives.omeka.net/items/show/1684.

- Ibid, 12.

- Jaycocks, Lucia H. “The Lords Proprietors Plantation and Palisaded Dwelling Compound 1670-1675”. Charles Towne Landing. February 23, 1973. Box 3, Folder 4B, Carr Family Papers Collection, Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC.

- “Hillsborough Plantation–West Ashley–Charleston County.” South Carolina Plantations. SCIWAY, 2019. https://south-carolina-plantations.com/charleston/hillsborough.html.

- Mr. Leonard A. Higgins Sr., quoted in Jaycocks, Lucia H. “The Lords Proprietors.”

- “Charleston City, South Carolina,” U.S. Census Bureau Quickfacts (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2019). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/charlestoncitysouthcarolina,charlestoncountysouthcarolina/PST045219.

- Patton, Stacey. Rep. The State of Racial Disparities in Charleston County, South Carolina 2000-2015. Charleston, SC: The College of Charleston, 2017. Pp. 32.

- Ibid.

Image Credits

- Map of Maryville. Box 3, Folder 2, Carr Family Papers Collection, Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC.

- Avery Research Center: Miriam DeCosta Seabrook and Herbert U. Seabrook Papers, 1882-1995. “Miriam DeCosta Seabrook.” 2010. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:5471.

- “West Ashely History Series: Maryville-Ashleyville.” Charleston County Public Library. October 4, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2021. https://www.ccpl.org/events/west-ashley-history-series-maryville-ashleyville.