» History News: The Denmark Vesey Plot by Kangkang Kovacs

Denmark Vesey was born, raised, and enslaved in St. Thomas (Danish West Indies). As a boy, he was purchased and sold several times before ending up in Charleston, South Carolina, the domestic property of a captain named Joseph Vesey. At age thirty-two, he won a lottery and bought his freedom for six-hundred dollars. Afterward, he worked as a carpenter. As a father and husband, he briefly considered emigrating to Sierra Leone with the whole family. But in the end, he decided to “stay, and see what he could do for his fellow creatures,”1 according to a friend. He helped to found the African Methodist Episcopal congregation (later known as the Mother Emanuel A.M.E. Church) in Charleston, the first independent Black denomination.

In 1822, he organized a significant slave revolt to engage in a mass exodus from Charleston to Haiti, where enslaved people led a successful revolution, which led to their independence from France. Two of the enslaved men involved leaked the plans, which resulted in White slaveowners thwarting the plot. Vesey was tried and hanged with thirty-four black men. The Charleston authorities sold forty-two others, including his son outside the United States, and demolished the Mother Emanuel Church he had helped to found in the aftermath.

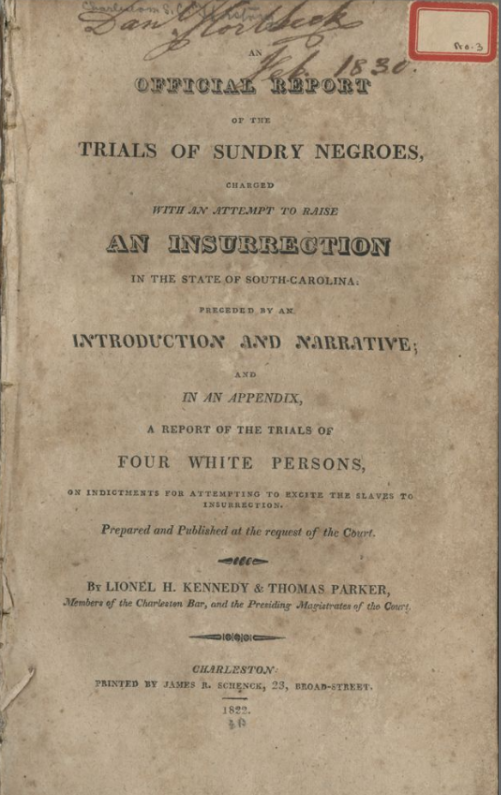

Vesey left behind a thin paper trail. No letters or diaries in his hand exist. In a history written by white men, Denmark Vesey remains voiceless. And nameless too: on the cover of this crucial historical document, the official report of Vesey’s trial in 1822, Vesey’s name is not listed. It reads An Official Report of the Trials of Sundry Negroes Charged with an Attempt to Raise an Insurrection in the State of South Carolina. “Sundry negroes” was all the acknowledgment he could get from those who sentenced him to death.

The memory of Vesey is divisive. His story has inspired many Black Americans and other activists throughout history, but often, the establishment and even local media has seen him as a threat.2 The divisiveness of this memory made it difficult to erect a statue in his honor. The committee working on the figure planned it to be in downtown Charleston in Marion Square but could not get permission from the landowner. The statue was eventually erected in 2014 in Hampton Park, a park far from the city’s historic district.

But the revolt Vesey plotted proved to be pivotal in Southern history. It marked the beginning of collective paranoia. The state legislature tightened its grip on formerly enslaved people after the Vesey plot, restricting their access to education and ability to travel while discouraging plantation owners from freeing the enslaved. South Carolina formed a militia to “establish a competent force to act as a municipal guard for the protection of the City of Charleston and its vicinity.”3 This municipal guard formerly named the South Carolina State Arsenal, later became known as the Citadel.

In 1822, the South Carolina legislature passed the “Negro Seamen Act,”4 requiring all free Black sailors on ships docked in Charleston to be imprisoned in the city jail when their ships were in port. The legislature passed the act out of fear that the free Black sailors from foreign countries would interact and influence Charleston’s enslaved population. This law was ruled unconstitutional shortly after in Federal court, as it violated international treaties between the U.S. and Britain. But the South Carolinians defended it vehemently, viewing it as a state’s right. The disagreement about the law was one of the many confrontations between the Federal and the State government that would eventually lead to the southern secession and the Civil War.

The famous contralto singer and civil rights activist Marian Anderson once said: “No matter how big a nation is, it is no stronger than its weakest people. And as long as you keep a person down, some part of you has to be down there to hold him down. So it means you cannot soar as you might otherwise.” In trying to defend its lineage of white supremacy and keep people like Denmark Vesey down, be it through trivializing or demonizing, a part of Charleston has stayed down there. As the dark, obscure pages of history come to a new light, so does our community rise and soar.

Source

- Douglas R. Egerton, He Shall Go Our Free: The Lives of Denmark Vesey, 2nd ed. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), chaps. 1-4, quotation on 123).

- Hunter Jack, Denmark Vesey Was a Terrorist, Charleston City Paper, Feb 10, 2010, https://charlestoncitypaper.com/denmark-vesey-was-a-terrorist/.

- Guidon. The Citadel. 1951-1952. https://archive.org/stream/guidon1951cita/guidon1951cita_djvu.txt

- Hamer, Philip M. “Great Britain, the United States, and the Negro Seamen Acts, 1822–1848.” Journal of Southern History 1 (February 1935): 3–28.

Image Credit

- An official report of the trials of sundry Negroes, charged with an attempt to raise an insurrection in the state of South-Carolina : preceded by an introduction and narrative : and, in an appendix, a report of the trials of four white persons on indictments for attempting to excite the slaves to insurrection. The College of Charleston Libraries. 1822. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:86359