» Archive Spotlight: Somebody Had to Do It by Mateo Mérida

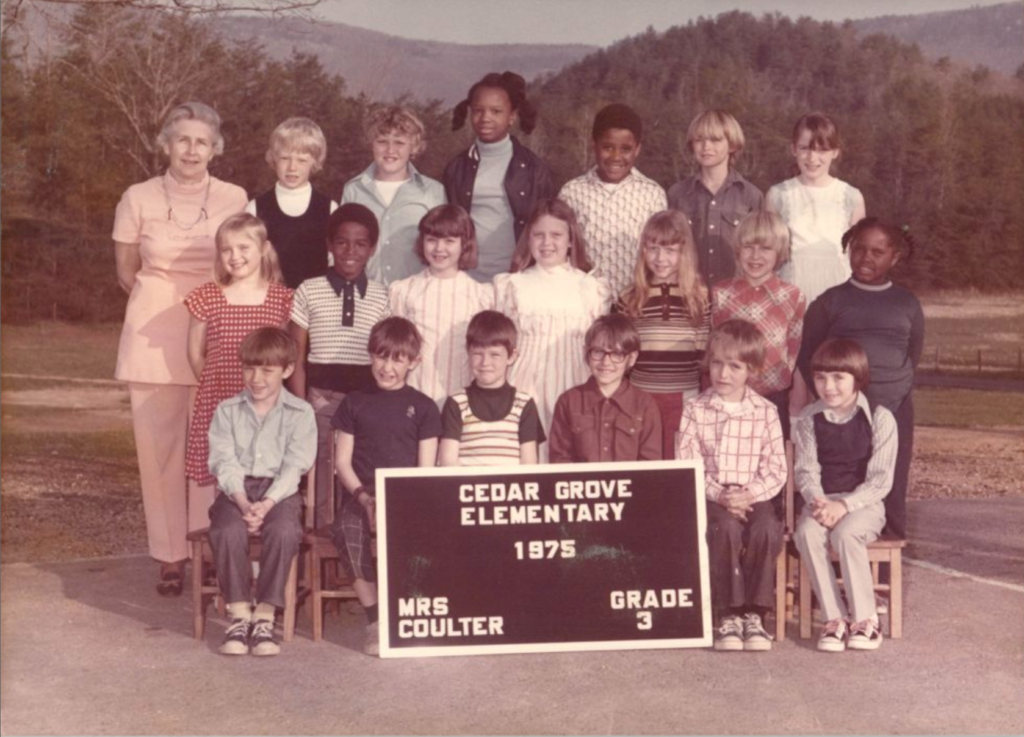

One of the prominent movements of the Civil Rights Era saw African Americans pursuing the highest quality education possible. Under Jim Crow laws, segregated education relegated the best education resources to white students, leaving young Black students with some of the poorest quality education in the country. In the 2009 collection Somebody Had to Do It, individuals who were integral to the integration of Southern schools, seeking to acquire a better education, shed light on some of the confrontations and adversities of the first Black students to attend classes in changing White-only schools.

Before transferring to the new schools, these interviewers recall the quality of education in the White schools was much higher than that of the Black schools which they attended. For Gloria Carter (in 7th grade at the time), the sheer disparity in quality alone was reason enough to enroll. She describes “This is something good, this is something better, it looks prettier, the busses are prettier. So it was just excitement. We were really excited about doing something better.” Many Black families were eager to enroll their children in white schools when given the opportunity, given how much better the quality of their education would be.1

While an improved education was a large benefit for Black students, this did not come without equally large sacrifices. Bullying was a regular occurrence. Theodore Adams remembers on his first day of class at his new white school, “Every time I got up out of my seat when I sat back down I sat on a tack. And towards the second period I had jumped up so many times that I refused to jump up again and I just endured it. I’d sit on it, pull it out, throw it on the floor.” To receive the best education possible, Adams knew enduring physical pain and torment were part of the steps necessary in dismantling a segregated education system. Adams understood that these acts were intended to scare him away from the school, which made it even more important that he did not give up on this change.2

Many Black students also found themselves isolated from their peers. By no means was this isolation a subtle or vague occurrence. Franklin Hull recalls “You’d find yourself in the far back, last row, of the classroom. As far as you can get away, as far they could put you away from the teacher and from the other classmates. You were told more than one way or another that you were not wanted, at all. ‘Why are you here’ was a question I was asked many a times.” The willpower of Hull and all other Black students integrating white schools cannot be understated. Black students did not reverse their enrollment, but instead graduated and paved the way for other students to follow in their footsteps because of their determination in withstanding incredible adversity.3

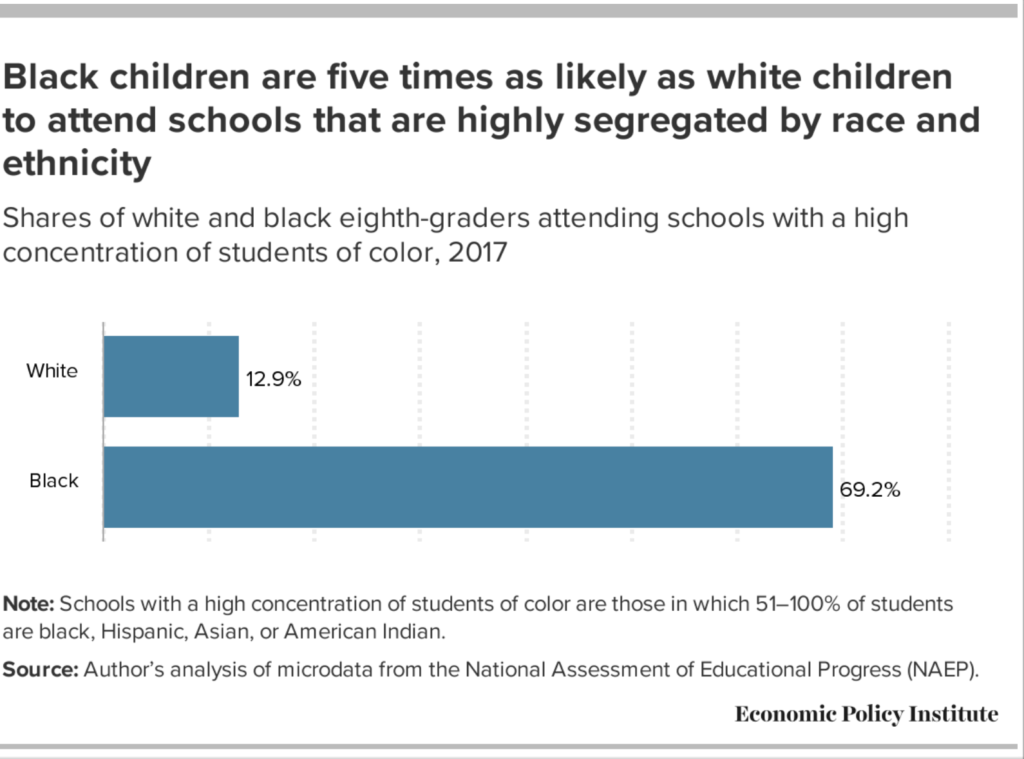

The students of the 1960’s and 70’s interviewed in the Avery’s collection of the Somebody Had to Do It oral histories are heroes because of their desire for quality education even if it meant integrating deeply segregated and oftentimes hostile white schools. They made incredible sacrifices for future generations of Black students to attend better schools. Unfortunately, integration is not only relevant to the 20th Century. While at one time segregation was a matter of law, it is still a matter of fact at present in some ways. According to the National Assessment of Education Progress, more than two-thirds of African American students attend schools with a high concentration of students of color. Similarly, 72.4% of Black 8th grade students attend high-poverty schools.4

Studying the memories of these trailblazing students, it is important to remember that the struggle for quality education in the Black community is still ongoing and there is still much work to be done.

Sources

- Carter, Gloria. “Somebody Had To Do It Collection: Interview with Gloria Carter” Avery Research Center: Somebody Had To Do It Collection. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. July 12, 2008. Accessed Jan. 19, 2022. Pp 4. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:114179.

- Adams, Theodore. “Somebody Had To Do It Collection: Interview with Theodore Adams” Avery Research Center: Somebody Had To Do It Collection. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. April 8, 2009. Accessed Jan. 20, 2022. Pp 6. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:80754.

- Hull, Franklin. “Somebody Had To Do It Collection: Interview with Hull Franklin” Avery Research Center: Somebody Had To Do It Collection. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. Oct. 18, 2009. Accessed Jan. 19, 2022. Pp 5. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:114180.

- García, Emma. “Schools Are Still Segregated, and Black Children Are Paying a Price.” Economic Policy Institute, February 12, 2020. https://www.epi.org/publication/schools-are-still-segregated-and-black-children-are-paying-a-price/.

Image Credit

- YWCA of Greater Charleston, Inc., Records, 1906-2007. “Photograph of a 3rd Grade Class, Cedar Grove Elementary School.” Lowcountry Digital Library Catalog Search, April 2017. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:116362?tify=%7B%22view%22%3A%22info%22%7D.

- García, Emma. “Schools Are Still Segregated, and Black Children Are Paying a Price.” Economic Policy Institute, February 12, 2020. https://www.epi.org/publication/schools-are-still-segregated-and-black-children-are-paying-a-price/.