» Part 3: Old Slave Mart and Charleston’s Historic Memory by Mateo Mérida

The end of the Wragg years saw a lot of mystery surrounding the future of the Old Slave Mart Museum. As the Wragg sisters struggled to create enough revenue to keep the museum open, the odds of the museum permanently closing its doors were exceedingly high. Fortunately, the City of Charleston, particularly then mayor Joe Riley, recognized the importance of the Old Slave Mart Museum, and was reluctant to watch the site close. To prevent as much, Riley and the City of Charleston purchased the site from the Wraggs early in 1989, with the plans to renovate it and reopen it to the public.

What the city could not have anticipated at the time was natural disaster, as Hurricane Hugo made landfall in Charleston that same August,. Because of the hurricane, and a plethora of other city related projects, the renovation of the Old Slave Mart would lay on the backburner for years to come. While much of the hurricane damage had been addressed by the mid-nineties, the City of Charleston was not necessarily interested in managing the site. In fact, it sat empty for so long that the Avery Research Center contemplated acquiring the site to utilize it as an interpretive center. While the City of Charleston contemplated what to do with the new Old Slave Mart Museum, it was often used as an occasional event venue throughout the mid-nineties.1

After nearly twenty years of anticipation, the Old Slave Mart Museum would re-open to the public on the Halloween of 2007. There were key differences distinguishing the newest Old Slave Mart from the preceding versions of itself. For one, the Museum is now in no way focused on Black craftsmanship or artisanship. Instead, the Old Slave Mart of today is unafraid of discussing the traumas of the history of slavery with the public. Instead of exploiting its reputation as a site of deep, racialized violence, the guests visiting the Museum leave with deeper understandings of slavery as a whole, how it was practiced, and why it defined so much of American economy, politics, and history.2

Today, the Old Slave Mart is not the only site in Charleston which discusses Black history, however, it is the only museum in Charleston that focuses exclusively on the history of slavery. It is an element of core component of several historic houses and plantation sites, but the Old Slave Mart carefully discusses the history of the slavery in South Carolina and in the Transatlantic Slave Trade in general. Visitors to the museum typically describe the museum as a somber but enlightening experience. For many, they are surprised to learn about how many countries participated in the slave trade, and how intrinsically economies like that of Charleston once were tied to the forced labor of African descended people.

Certainly, part of what makes the visit so impactful is because the Old Slave Mart Museum reflects its own history as a slave auctioning site, displaying multiple broadsides which advertise the auctions that took place on 6 Chalmers. While other sites in the Charleston area show visitors how they would have worked and lived, the Old Slave Mart forces visitors to reflect on the slave trade itself. Broadsides list prices of enslaved persons in their respective years, a chart presents different prices of individuals by age, and images throughout the museum show what auctions would have looked like across Charleston, and at the site itself. Lesesne, Wilson and the Wraggs did not want to look into the eye of the separation of families on 6 Chalmers, but no visitor in today’s Old Slave Mart leaves without being forced to do so.

The current Old Slave Mart does not commodify the labor of slavery itself, but rather offers reflection of the damages caused slavery. This is a radical change of the museum’s interpretation as it departs from the apologist perspective of slavery in the twentieth century, and also criticizes the opportunist but exploitative perspective of Thomas Ryan.

Like older versions of the museum, it still has room to improve. I would argue that the museum would benefit from discussing at more length how slavery continues to define the historical memory of Charleston today. Similarly, there are no panels which discuss Reconstruction, the Great Migration, or how slavery was the foundation for future practices like Jim Crow, Mass-Incarceration, and hate groups like the KKK.

Yet, many will retort it is not the responsibility of one single (small) site to engage with the consequent elements tied to slavery. To that credit, Charleston as a whole is in a far better position than it was even in 2007, as the Old Slave Mart is no longer the only Black history interpretation site in Charleston. McLeod Plantation discusses Reconstruction and the lives of the enslaved at incredible length. Tour guides like Damon Fordham and Alfonso Brown have tailored tours with the purpose of underscoring the Black history and Gullah Geechee culture in Charleston. This coming January, after decades of discussion and planning, the International African American Museum will open up and underscore all of these issues, and many more that are not within the scope of other tours and sites.

Nonetheless, it is crucial not to fall in the same trap as older versions of the Old Slave Mart, who have proactively chosen to look past the current impact of slavery, instead deciding to relegate it as a lost relic of the past, as if these events do not impact the politics of today. Slavery itself fundamentally political, but the way slavery is presented to the public is political as well. In the wake of events such as the Mother Emmanuel massacre, The War on Drugs, the unlawful executions of Trayvon Martin, Walter Scott and Breonna Taylor, among a plethora of other issues impacting all Americans along the lines of race and class, the discussion of slavery needs to be tied to the way it impacts the world of today.3

Charleston has the 12th largest tourist economy in the United States (in proportion to the size of its workforce). Given the industry’s scale, Charleston has the means to completely change how visitors understand how slavery and race relations as a whole have impacted the United States.4 Charleston has taken great strides to improve how it educates the public in these matters. While these are not developments that have come easily, the development is not over.5

Sources

- Behre, Robert. Charleston mulls new role for Slave Mart Museum. The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC. Feb. 27, 1995.

- “Old Slave Mart Museum will reopen Wednesday.” Post and Courier: Charleston, SC. Oct. 30, 2007.

- Avery Research Center. The State of Racial Disparities in Charleston County, South Carolina. College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. 2017.

- Gandhi, Mitul. “U.S. Cities Most Reliant on Tourism.” Seo Research. SeoClarity: Buffalo Grove, IL. Sep. 29, 2020. https://www.seoclarity.net/blog/us-cities-most-reliant-on-tourism.

- This series of posts has managed to discuss a specific case study of one specific example of the evolution of the memory of slavery in Charleston. For more discussion about how the city as a whole has navigated this conversation, be sure to read Kytle, Ethan J. and Blain Roberts. Denmark Vesey’s Garden: Slavery and Memory in the Cradle of the Confederacy. The New Press: New York City, NY. 2018. I only read this book after having written these posts, but these make an excellent complement to the discussion of slavery in the Holy City.

Image Credit

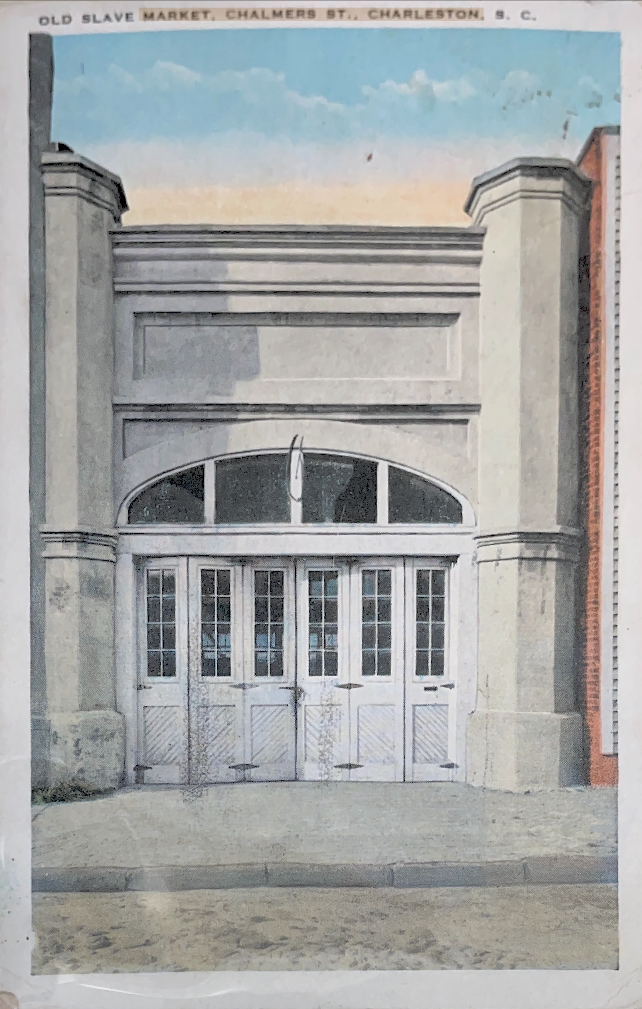

- Postcard, 1929. Box 1, Folder 1. Old Slave Mart Museum collection. Avery Research Center at College of Charleston: Charleston, SC.

- “[ARCHIVED] Old Slave Mart Museum Celebrates Black History Month, Open Sundays in February.” News Flash Home. City of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Jan. 31, 2022. Accessed Dec. 14, 2022. https://www.charleston-sc.gov/CivicAlerts.aspx?AID=793&ARC=1314