» Part 1: Lowcountry Resistance by Mateo Mérida

The 2023 Black History annual theme is Black Resistance and in honor of this for February 2023 we will be posting a weekly post on this topic with a SC Lowcountry focus.

Content Warning: This blog post contains discussion of torture and violence that may not be suitable for some readers.

A common failure of the educators and public historians of US history is to inadvertently depict Black Americans as passive participants of history. Whether discussing chattel slavery, Jim Crow apartheid, or Mass-Incarceration which have deeply impacted the experiences of African American people, it can be easy to discuss what happened, and neglect the discussion of how people responded to these injustices. African American people did not passively accept the injustices of their day, and have instead protested, rebelled, and risen to confront the injustices of American history. In accordance with the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, this Black History Month, I will present four weekly blog posts which will discuss Black resistance in the Lowcountry. Each of these will discuss a unique period of history and emphasize different forms of resistance seen in each case study. As the first post of this series, this write-up will discuss how Black people confronted slavery, in what is a somewhat obscured rebellion in the history of the city.

For chattel slavery to have existed for such an astonishingly long period of time in the Lowcountry, there needed to be a mechanism to coerce enslaved people into compliance. That mechanism was terror. Institutions were founded on the premises of sheer violence, the separation of families, and inhuman conditions, to prevent enslaved people—who were most of the population in antebellum South Carolina—from resisting their subjugation. No institution better defines that history of violence than that of the Charleston Workhouse, dreaded by the enslaved and championed by enslavers. Yet, even as a tool of violence and oppression, it became the site of one of the most obscure but most important insurrections in the history of Charleston. Despite the state sanctioned and privatized violence of the Workhouse, Kelly’s Rebellion of 1849 serves as a prime example that even the terror of violence cannot deter people’s right to fight their own oppression.

The rebellion that transpired at the Workhouse was spontaneous and is centered on one key figure named Nicholas Kelly. Kelly was forced by his enslaver to relocate from his home in New Orleans to Charleston. After arriving in South Carolina, Kelly was put on trial for assaulting two white men, despite acting in his own self-defense. Found guilty, and sentenced to death, he successfully appealed to change his sentence to three years at the Workhouse. There, he would establish a relationship of some unclear kind with an enslaved woman. On July 13th, John Gilchrist came to the Workhouse, with plans to remove her from the Workhouse, separating her from Kelly, perhaps permanently. Kelly, and several others fought off Gilchrist, and as they anticipated retaliation from the Workhouse authorities for their actions, Kelly began to organize. He recruited the incarcerated people of the Workhouse to join him, expressing “‘There [will] be war today’ and that he wanted ‘every man, who called himself a man, to be a man.’” In this statement, Kelly shows that despite him being convicted for his own self-defense and having spent his life under the oppression of slavery, Kelly still recognizes the humanity of himself and the other members of the Workhouse. Neither slavery nor the Workhouse were successful in breaking the spirit of enslaved people, and they were ready and willing to destroy the institutions that oppressed them.1

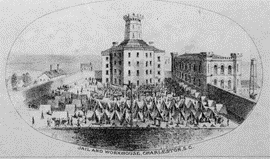

Kelly’s Rebellion was so significant because it threatened to shatter what the Workhouse was as a violent, corrective institution, and therefore slavery as a practice. The structure that would become the Workhouse was built in the 1730s, and was a shelter for the poor, a hospital, and it was also a sugar processing establishment. Because of this, it would come to be euphemistically known as the “Sugar House.” Later, while the neighboring jail incarcerated free people of color and white Charlestonians, the Workhouse was used explicitly for the punishments of enslaved people as early as 1783. Like the jail, enslaved people would be put to trial, and would be sentenced to the Workhouse, where the enslaved would be whipped, paddled, and forced to manual labor.

The historic memory of the Workhouse transcends generations. Marcellus Forest was born and raised in Charleston, like many of his ancestors. Reflecting upon the experiences of his once enslaved father, he describes “…he broke out running and he our ran him and all [laughs], because he said that he knew that then end of that run if he didn’t run fast enough, he’d have to go to the sugar house.”2 This interview was recorded in 1981, 116 years after the abolition of slavery. Despite the generational difference and the passage of time, Forrest’s inherited memory of what the sugar house was still informed his family’s understanding of slavery in Charleston.

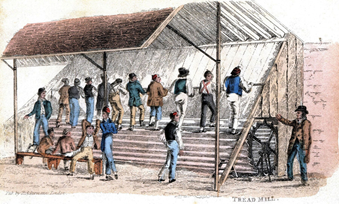

If the Workhouse pushed him to keep running, what was it more precisely about the Workhouse that made him run? Simply put, the Workhouse would not have terrorized enslaved people if it weren’t for the violence which was exacted there. Whipping was certainly one of the most common forms of punishment for the Workhouse’s enslaved prisoners. The institution also enthusiastically employed the psychological violence of solitary confinement. The workhouse was particularly famous for using a treadmill as a device of torture, tasking the enslaved to run for hours straight, which made it abundantly painful and difficult to walk in the coming weeks.3

James Matthews was once one of the numerous people who sought self-emancipation by fleeing from his enslaver but came to be incarcerated in the Workhouse. He recalls that his back “would be full of scabs, and they whipped them off till I bled so that my clothes were all wet. Many a night I have laid up there in the Sugar House and scratched [the scabs] off by the handful.”4 Violence was a tool to coerce enslaved people to accept their subjugated status, with explicit consequences for rejecting it in any capacity that compromises this status. Beyond punishing the enslaved individuals for their perceived discretions, the Workhouse’s reputation was a threat that loomed in the minds of the enslaved all throughout the Lowcountry, attempting to force the enslaved, proudly rebellious, or otherwise, to submit to white supremacy.

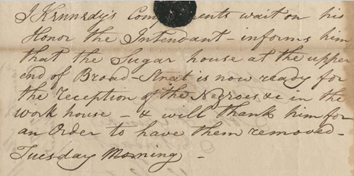

The Workhouse was not solely an institution of law enforcement, as it was also privately available as an extralegal punishment determined by enslavers to send the laborers who they enslaved. One such example of this comes from Judge John Grimké, the father of well noted abolitionists, Sarah, and Angelina Grimké. Grimké received correspondence with the Workhouse, that stated “…the Sugar house at the Upper end of Broad-Street is now ready for the reception of the negroes as in the Workhouse & will thank him for an order to have them removed Tuesday morning.”5 The violence exacted at the Workhouse was so normalized, that the letter reads like that of scheduling of an appointment or a stay at a hotel. For white supremacist chattel slavery to work, enslavers believed that the humanity of enslaved people needed to be totally removed for them in order to perpetuate their insubordination. As a result, for enslavers like that of Grimké, they viewed inhuman violence as an ideal tool for whatever they determined to be insubordination.

Despite the reputation of the Workhouse, in the eyes of enslavers and the enslaved, it did not petrify the enslaved to the point of passivity, as the Workhouse itself would become the site of an insurrection itself. It is not explicitly clear what exactly the goal of the Workhouse Rebellion was, beyond escaping from the Workhouse. Maybe retaliating against the people who had tortured the likes of Kelly for years was the pure objective. It could be that Kelly’s band of prisoners sought to flee Charleston and flee to wherever they could be free. It may be possible that they only intended to be reunited with their families, fully understanding the impending consequences of challenging their oppression. Perhaps Kelly sought to destroy the white supremacist city of Charleston that dehumanized people like those at the Workhouse for the ultimate profits of a small minority of people. Nonetheless, in the coming week, Kelly and several others would be incarcerated, and executed by hanging in the jail yard as a public spectacle.6

Whatever they had intended to do, the consequence is the same. Kelly’s Rebellion shows that terrorism—which was the mode of which the Workhouse operated to coerce the enslaved into compliance—is not powerful enough to prevent the oppressed from seeking to end their oppression. Slavery had shown them violence, so in defense of their own dignity, they responded in violence. Slavery had taken so much from the people of the Workhouse and strove to strip the enslaved of their own humanity. Instead, it only pushed enslaved people to recognize their own humanity in the face of their suffering, and they fought to preserve it, even though they knew it would cost them their lives.

Sources

- Strickland, Jeff. All for Liberty: The Charleston Workhouse Slave Rebellion of 1849. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. 2022. 116-122.

- Forrest, Marcellus. “Oral history interview with Marcellus Forrest.” Oral Histories Collection. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Feb. 21, 1981. Pp. 25. Accessed Jan. 31, 2023. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23390

- Strickland, 41.

- The Liberator, September 13, 1838, September 30, 1838. quoted in Williams, Joseph. “Charleston Work House and ‘Sugar House.'” Discovering Our Past. College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Nov. 16, 2020. Accessed Jan. 31, 2023. https://discovering.cofc.edu/items/show/31

- Kennedy, James. “Message to John F. Grimke from Sheriff James Kennedy, August 7, 1787.” Aug. 7, 1787. Grimké family papers, 1679-1977. College of Charleston Libraries: Charleston, SC. Accessed Jan. 31, 2023. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:80683

- Strickland, 130.

Image Credit

- Williams, Joseph. “Charleston Work House and ‘Sugar House.'” Discovering Our Past. College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Nov. 16, 2020. Accessed Jan. 31, 2023. https://discovering.cofc.edu/items/show/31

- Ibid.

- Kennedy, James. “Message to John F. Grimke from Sheriff James Kennedy, August 7, 1787.” Aug. 7, 1787. Grimké family papers, 1679-1977. College of Charleston Libraries: Charleston, SC. Accessed Jan. 31, 2023. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:80683

- Waters, Leon A. “Jan. 8, 1811: Louisiana’s Heroic Slave Revolt.” Jul. 1, 2013. Zinn Education Project: Washington, DC. Accessed Jan. 31, 2023. Thumbnail image. https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/louisianas-slave-revolt/