» October is American Archives Month: African American Burial Sites in Charleston, South Carolina by Mateo Mérida

This blog post is written by Mateo Mérida, who is a graduate student for the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture during the 2021-2022 academic year. Mérida is a student in the College of Charleston's History Department.

As a city that is more than 350 years old, Charleston is the final resting place of many hundreds of thousands of people who have lived here throughout the course of its history. A sizable portion of these burial places belong to people of African descent who constituted a majority of the population for most of the 350-year history. Despite the important role African American people have played in shaping the Charleston we know today, many of these burial sites are under threat, furthering the difficult history the sites have faced for generations.

In downtown Charleston, many people visit the cemeteries that lie outside of the churches which characterize the “Holy City.” While cemeteries are an inescapable sight to the city’s visitors, not all of these cemeteries are as well known.

Oftentimes, enslaved Africans were buried with items like the beads come from the Avery Archive’s McLeod Plantation Cemetery Collection. While McLeod Plantation today is a fraction of the size that it once was, some of its burial grounds just off the banks of Wappoo Creek are open to the plantation’s visitors. Having been reduced significantly in size, one can speculate that there may very well be other burial sites that were used by enslaved people, which lie away from the current property’s grounds. This is likely true all across the Charleston area.

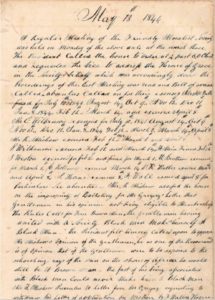

There were also burial societies established by free people of color prior to the Civil War. For example, the Friendly Moralist Society operated in Charleston during the mid-1800’s as a free brown (or multi-ethnic) man’s group and actively restricted membership, prohibiting or non-mixed-ethnic Black men from joining.

The meeting minutes of this society on May 13th, 1848 discusses the rejection of a Black man’s application for membership on the grounds of him being just that—a Black man. It is also noted that he was already affiliated with a different society for Black men. These minutes elaborate “Mr. R. Mishaw accepted the house on the impropriety of Balloting for Mr. Gregory’s Letter that [the] Gentleman in his opinion not being eligible for Membership. The Rules Call for Free Brown Men, the gentleman having united with a Society Black man make [sic] himself a Black Man.” While Mr. Gregory may have already had associations with members in a similar free Black men’s society, these restrictions raise questions about the burials of other African American people: what similar societies existed for free African American women? What resources existed for enslaved people to bury family members who were institutionally owned—by a school, shop, or other establishment—instead of owned by individual people? Given these restrictions, it is inevitable that the whereabouts of all buried free people of color in Charleston may never be fully determined, as not all people had access to resources such as the records which have been maintained by the Friendly Moralist Society.

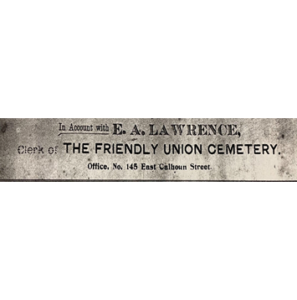

Importantly, other organizations like the Friendly Union Society (1813-1981) aided in the burial of a number of free people of color. The Avery archives houses many important documents to help indicate the locations of such burial grounds in the Charleston area. Similarly, the Friendly Union Society Cemetery still exists today on Cunnington Avenue on Charleston’s upper peninsula.

Still, while some groups like Friendly Union Society and Friendly Moralist Society have worked hard to record and aid in the process of burying free people of color in Charleston. With today’s rapid development and expansion of the Charleston area, these burial grounds that were—lost for decades, if not centuries—are being rediscovered once again such as those described by Adam Parker in the Post and Courier article “How new development in Cainhoy threatens historic burial grounds.” With the vast collection of records at the Avery Research Center, perhaps more of these grounds may be found once again, before they have been lost permanently in the rapid development within the Lowcountry.