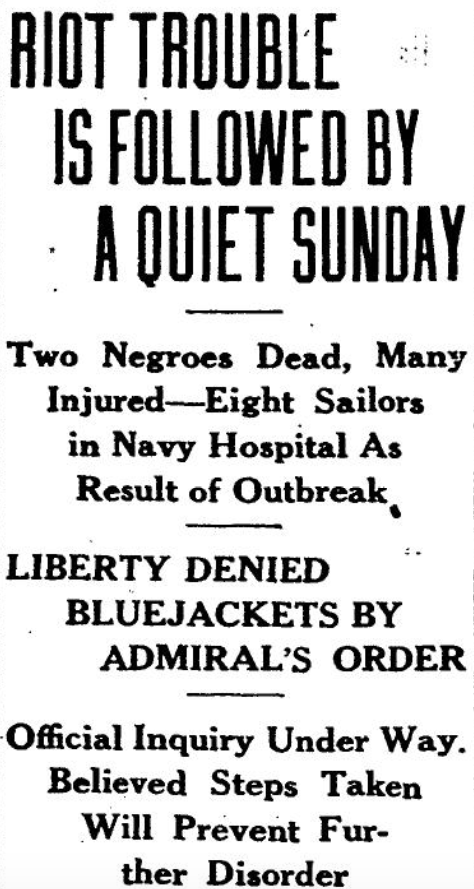

» Lowcountry Resistance Part 2 by Mateo Mérida

As we saw in Kelly’s Rebellion of 1849, the first thought of resistance for some is that which is violent. As valid as forms like rebellion are in resisting oppression, it is not the only form of resisting. In the face of a deeply violent and traumatic episode in the history of Charleston, African American people found more subtle ways to. In spite of the ambivalence, lack of accountability, and victim blaming, from the Riot, Black Charlestonians resisted but continued to carry on everyday life.

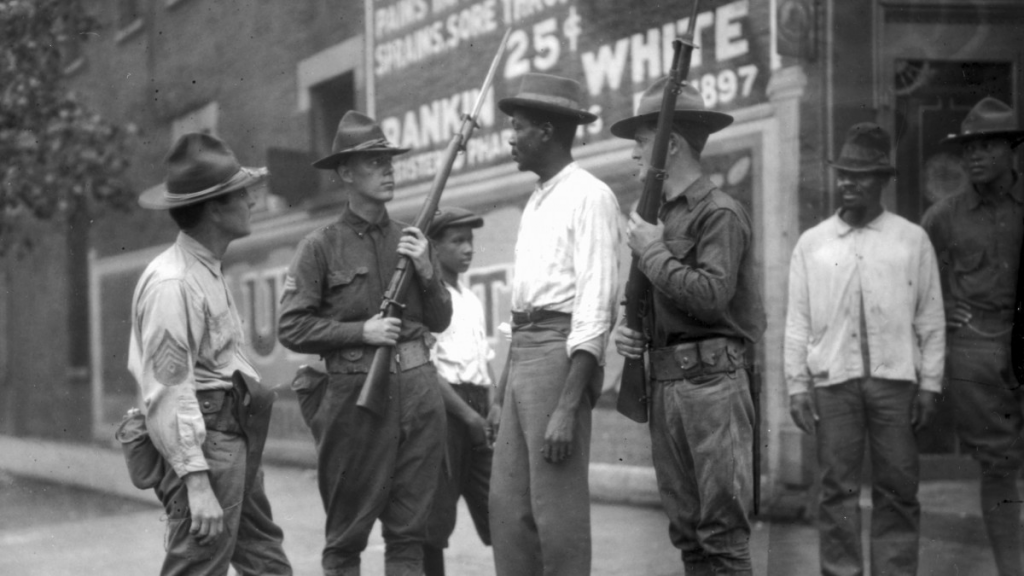

As was true all throughout the United States, Charleston race relations were tense in 1919. After the end of the First World War, Black soldiers who had fought in Europe deeply resented their return to the South, steeped in Jim Crow apartheid. Similarly, white Southerners deeply resented the return of the Black veterans. They also resented their new neighbors, as this coincided with the Great Migration, where Black Americans relocated from rural areas to urban centers such as Detroit, Atlanta, New York, and Chicago. The Charleston Naval Base became a powder keg, creating a concentration of both segregationist Southerners and resentful Northerners which would erupt in the late spring of that year.1

There is a lot of mystery surrounding the night of May 10th, 1919, namely because it took place over the weekend and in the late evening and into the night. Thus, in the following workweek, newspapers struggled to separate fact from fiction. It is not clear what started the riot. One version of events describes that the riot began because a white sailor accused a Black man, who had sold him whisky, of shortchanging him. Their dispute resulted in gunshots, which then erupted into a full-fledged riot. Another version of events describes sailors who stole items from a pool hall, and the establishment’s Black customers followed them into the street, and a riot ensued. Yet another version describes a Black man as having shot a white sailor.2 While the cause of the riot may never be known, these versions commonly recall that navy seamen on leave from the Naval Base had some sort of altercation with African American people, and used that as an excuse to terrorize the entire community.

The attacks from the riot were random and unfocused, but afflicted Black individuals and Black business alike. A Black man fled from his accosters and took refuge in Fridie’s Central Shaving Parlor, a Black owned and operated business at 305 King Street. When the rioting crowd was unable to locate him from the exterior, they broke the windows, and destroyed the property searching for him, before they realized he had run out the back door. The attacks were so unfocused and random, that navy men threatened a Black man riding in a streetcar to get off the vehicle. Once he did, the sailors beat the man in front of his wife who remained in the car. Within a matter of hours, Roper Hospital was overrun by injured people, the marines were deployed to reestablish order, and two Black men lost their lives.3

In the following days, it became clear that the city of Charleston blamed the seamen for directly causing the riot, and that the riot targeted Black Charlestonians. In the News and Courier, Charleston mayor Tristram T. Hyde described “‘I will ask that W.G. Fridie, whose barber shop on King Street was demolished by the sailors, to draw up a bill of damages to be presented to the city government. This might set a precedent, but the Negroes of Charleston must be protected.’” Here, the mayor clearly acknowledges that the worst of the riot was felt by Charleston’s Black community. However, even though the riot impacted Black people the most, not even the mayor was empathetic to the violence they suffered. Instead, protecting the Black community was a matter of keeping the peace. “We are hoping that this morning saw the end of the disturbances, but if any action is taken by the Negroes against the whites or vice versa, I will ask that martial law be established.” His statement to the newspaper completely redirects responsibility from the riot. While he acknowledges that Black Charlestonians did not cause the riot and that white Charlestonians are likely to continue the violence, he is threatening the entire city with martial law on the occasion that Black community may decide to retaliate.4

In addition to the mayor’s ambivalent attitude, the News and Courier proceeded to victim blame the Black community. Such was the case with Isaiah Doctor (mistakenly referred to as Isaac in the newspaper).5 The article suggested he was somehow responsible for his own death. “One version is that Doctor jostled through two bluejackets, who remonstrated. Doctor is reported to have hurled epithets at the two white men and then to have committed assault with a weapon.” They do not provide another version. Instead, the article was written so that the reader comes to the same conclusion as the newspaper, that if Doctor hadn’t been so confrontational (not to be conceived as self-preservation), he wouldn’t have been murdered. This is a pattern of victim blaming continues throughout this entire article, as the actions of the rioting sailors are alluded to but never explained, while the actions of Black people are overtly described as senseless acts of violence.6

To be perfectly clear, Black people did not passively accept the violence of the riot, and consistently defended themselves throughout the long night. One other article described that while seamen targeted Black people, “Negroes, in many instances, threw brickbats and used pistols” to defend themselves.7 As the riot enveloped the city, it was noted that some Black chauffeur drivers working that night carried firearms with them, most likely to protect themselves from the rioters while they worked.8

Aside from African Americans defending themselves against the violence, very few white people were held accountable for the riot. For example, Jacob Cohen, and George Holliday were found innocent of Doctor’s murder. Instead, they were charged with rioting, and only served one year each incarcerated on a naval brig. Similarly, William Brown, a Black man who fled from an armed officer, was shot in the knee and succumbed to his injury days later. His killers were acquitted of all charges.9

After the riot, and the media’s gaslighting of the Black community as to why the riot took place to begin with, Black Charlestonians continued to find ways to recover. The riot pushed the Black community to be more vocal in their demand for Black police officers. Similarly, organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People pressured the rioting seamen to be held accountable for the violence they brought to the city.10

While the real perpetrators of the riot were slapped on the wrist, and there would be no Black officers added to the police force, Black Charlestonians resisted by moving forward. The violence transpired because of the mere presence of Black people, so Black people continued to keep their presence in the spaces that were rightly their own. As was expected in the News and Courier, W.G. Fridie filed to have his business restored.

Like Fridie, other organizations in the Charleston area also continued business as usual. The Colored Women’s Branch of The Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) in Charleston wrote a monthly report describing the activities of the group. They describe “Results would have been more full and satisfying had not been racial dicturbences [sic] in the city immediately preceding the larger number of th [sic] month’s programs, thus intimidating many[,] causes them not to venture out after dark.” As would be expected in a traumatic event, the members of the organization did adjust their actions to the recent violence within the communities. But, they did not cease their actions completely. Instead of surrendering to the violence of the riot, the YWCA carried out their regular obligations, regardless of the potential for more violent outbreaks.11

This business-as-usual approach extends well and long beyond the time of the riot. James Frayer was a cobbler on Morris Street in 1919. On the night of the riot, six sailors and a civilian shot bullets through Frayer’s shop windows, permanently disabling his apprentice. Nonetheless, Frayer continued to live and work in Charleston as a cobbler for the rest of his life. Despite the actions of the assailants, in the grand scheme of Frayer’s life, the riot was just one day in a long career in Charleston.12

The riot was another clear demonstration to Black Charlestonians that the city government did not exist to protect them. Instead, it saw them as people who need to be placated, even in circumstances that have everything to do with self-defense. From the municipal and naval legal systems to law enforcement and the media, anti-Black violence did not mean adjusting anything to make Black people feel safer or secure in the city in which they lived. In an urban setting which communicated to the people who lived there that the problem was African Americans, not rioting sailors, Black Charlestonians did not surrender their daily life to anyone. In the view of the city of Charleston, resistance to violence could only be practiced through retaliating in more violence, leading them to threaten Black Charlestonians with martial law if they retaliated. However, Black Charlestonians instead resisted by persevering.

Sources

- McWhirter, Cameron. Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America. St. Martin’s Griffin: New York, NY. 2012.

- Butler, Nic. “The Charleston Riot of 1919.” Charleston Time Machine. Charleston County Public Library: Charleston, SC. May 10, 2019. Accessed Feb. 1, 2023. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/charleston-riot-1919

- “Race Riots Occur Here.” Charleston News and Courier: Charleston, SC. May 11, 1919. Pp 3.

- “2 Dead; 27 Wounded in Street Rioting.” Charleston News and Courier: Charleston, SC. May 12, 1919. pp 8.

- Butler.

- Ibid.

- “Riot Trouble is followed by a Quiet Sunday.” Evening Post: Charleston, SC. May 12, 1919. pp 9.

- “Race Riots Occur Here.” Pp 3.

- Butler.

- Pennebaker, Mills. “Legacies of Slavery and Black Resistance in the East Side Community, Charleston, South Carolina,” thesis. College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. 2021. pp. 89. Accessed Feb. 1, 2023. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2547455750?pq-origsite=primo

- Beatrice D. Walker. “Coming Street Y.W.C.A. Report for May 1919” in YWCA of Greater Charleston, Inc., Records, 1906 – 2007 Collection. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. 1919. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:116147

- “Social Security Death Index,” s.v. “James Frayer” (1897-1951), Ancestry.com. Accessed Feb. 1, 2023. https://www.ancestrylibrary.com/imageviewer/collections/8741/images/VRDUSASC1821_089066-00422?pId=816635

Image Credits

- Higgins, Abigail. “Red Summer of 1919: How Black WWI Vets Fought Back Against Racist Mobs.” History Stories. History.com. Jul. 29, 2019. Accessed Feb. 1, 2023. https://www.history.com/news/red-summer-1919-riots-chicago-dc-great-migration

- “Riot Trouble is Followed by a Quiet Sunday.” Charleston Evening Post. Charleston, SC. May 12, 1919. Pp9.

- Higgins.

- The current site of Jordan Lash was once the site of Fridie’s barbershop on 305 King St. Jordan Lash Charleston. Untitled. Facebook: Menlo Park, CA. Oct. 3, 2022. Accessed Feb 1, 2023.