» Longshoreman Strike 1866 by Mateo Mérida

South Carolina has earned a reputation as one of the most conservative states in the United States, socially, politically, and economically. Part of this reputation comes from its practices to eradicate union organization within the state. In 2022, a scarce 1.7% of the South Carolina workforce held union membership.1 Despite this, there is a proud legacy of union membership in South Carolina. In Charleston, longshoreman are one of the longest standing and most successful professions in history of union organization in the state, extending as far back as the Reconstruction era.

To discuss the longshoreman in its earliest days, it needs to be clear that there are very few primary sources readily available about who these people were. This is for a handful of very interconnected reasons. Firstly, most longshoremen—previously called stevedores—in the Antebellum period were enslaved. Work in the docks, much like it is today, is very physical, intensive, and dangerous, making the labor to sustain the docks highly undesirable for people who had the freedom to choose their life’s profession. The absence of white faces early on meant that those wealthy enough to benefit from the labor of dock workers did not often interact nor consider the lives of the enslaved people who worked the docks. In this way, they are consistently absent from the records of the literate people of the time. This, coupled with slave codes that prohibited enslaved people from the practice of reading and writing, has contributed to the absence of longshoremen from archival sources.

However, what is known about the longshoremen is that the nature of their work changed very suddenly after 1865. After the Civil War and the implementation of the 13th Amendment, these laborers were now paid to work the docks. This does not mean they were paid fairly. In the two years after the Civil War, it was not at all uncommon for longshoremen to earn $0.75 for an entire day’s work, the equivalent of $14.50 in today’s money.2 In the minds of these employers, the pay was justifiable, because the people who they employed were once enslaved. What they (willfully) failed to consider was that these laborers, who had performed this work most of their lives, understood their work was worth more than the pennies they were paid.3 The fact that they were no longer enslaved completely changed how they related to their labor. Slavery created a relationship to labor that forced people to work against their own independent volition. If they chose not to work, the law supported physical and psychological violence, the separation of families, and forced starvation. Laboring as a paid worker completely changed the dynamic.

While still in the favor of the corporation or employer, paid workers agree to work under specific terms and conditions, with the understanding that they would receive a wage. Unlike in slavery, paid workers that choose not to work expected to lose pay, without the immediate suffering and life-threatening consequences guaranteed under slavery. If a worker did not comply with the terms of the agreement of pay and work respectively, they could be severed from the position (fired) or they may decide to find other work (quit). If the conditions that workers experience are difficult, the firing or quitting of an individual worker does not necessarily create positive change for the workplace. However, if the workers decide to reject the agreement to work as a unit (through work stoppages, strikes, holding leadership accountable, bringing mistreatment, unsafe or unjust working conditions to government attention, or even militancy) they can create meaningful change together through their sheer force of numbers in comparison to the small numbers of the business owners and managers.

After the Civil War’s end in 1865, the once-enslaved workers of the docks rapidly understood all the new rules and ways that their relationship to their own labor had changed and, beginning in 1867, participated in work strikes and stoppages demanding better pay. These demonstrations raised their pay up to $2.50 per day. As dock workers began to create success in raising their pay, employers in the shipping industry responded by hiring white laborers to break the longshoremen’s strike. Hiring white stevedores in response to organized Black laborers intended to create an image of radical ex-slaves opposed to hard work and who can be replaced by white laborers that don’t complain about working conditions. In response to this tactic, the Black longshoremen banned together, founding the Longshoremen’s Protective Union Association of Charleston (LPUA), in March 1869.4

The creation of the union did not mark the end of the protests of the longshoremen. Instead, the creation of the union guaranteed more activity. The longshoremen would take on several issues to improve the fruits of their labor and ensure protections for their work. Some successfully increased wages as high as $4.50 in some docks, and implemented overtime pay for those who worked beyond the hours of 7 AM to 5 PM. The strikes that the LPUA organized also confronted the strikebreaking tactics used by dock employers, as they also demanded that dock employers only hire a longshoreman if they were enrolled with the LPUA. Illustrating how powerful the LPUA would become in Charleston docks, on October 28, 1869, cotton shippers refused to hire the ship of George B. Stoddard, an LPUA member, reportedly because of his Republican political leanings. In direct response, 300 dock workers, many of whom were LPUA members, went on strike. Soddard was reinstated within the week, and the longshoremen returned to business as usual.

While the enslaved laborers of the Charleston docks may have been overlooked by Charlestonians in the past, the LPUA was front and center in the city’s attention. Local newspapers consistently reported on the dock’s happenings in highly racialized and unfavorable terms. One newspaper described:

It is a matter of profound regret that we are compelled to chronicle a proceeding so violative of public order and decency on the part of the colored people, particularly as it had no sort of foundation in justice or reason… It is just as well that the colored people should understand at once that, like the white people, they must live on the results of their labor alone, and if they are unwilling to submit to this law it will be easy enough to have their places supplied.5

“Strike Amongst the Wharf Employees,”

This statement reflects the public’s attention to the docks in two ways. First, attention on the docks was so widespread that white journalists complained about continuing to report on the longshoremen. Secondly, these labor tensions on the docks remained so eventful that these same journalists depicted the striking longshoremen as belligerent workers with unrealistic goals. Instead of describing the longshoremen and the LPUA as fighting tirelessly to improve the quality of their place of work, they portray them as people who do not understand what it means to labor for wages. The media was so focused on describing the LPUA as fighting with no end in sight, that they actively confirmed that they continued to win battles to improve their working conditions on a regular basis.

The incredible momentum of the LPUA would stall out in the 1870s. With the Panic of 1873, one of the longest economic depressions in the history of the United States, the volume of ships traveling to and from Charleston ports began to decline. Furthermore, the anti-union policies of local government officials, such as that of mayor George Cunningham, were part of their political strategy.6 The LPUA would see even more adversity with the 7.3 magnitude earthquake that devastated the entirety of the city in 1886.7

Yet despite this, the decline in shipping did not mean the end of the LPUA. While the union would ultimately dissolve in 1921, it was restored under the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) during the Great Depression in 1936. Even today, the ILA continues to carry the proud legacy of the once enslaved laborers, who performed radical organization in the Charleston wharves. Since World War II, it has created community leaders within the ILA, George German and Kenneth Riley, being two of the most prominent.8

The figure of the 1.7% of South Carolina workers who are a part of a labor union is the worst in the country, with the second worst being North Carolina at 2.8%.9 Ever since the pandemic, labor unions have been a focus of economics and politics, with the previous CEO of Starbucks under investigation for illegal union busting tactics.10 Simply put, working class people are pursuing means to have more say in their own work. As more and more working people continue to take interest in seeking union representation in their workplace throughout the country, the Longshoremen’s Protective Union Association is an important example of the historic successes of the labor movement and an inspiration for workers today.

Sources

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, “News Release,” Jan. 19, 2023, accessed Apr. 5, 2023, pp 12, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf.

- Ian Webster, “CPI Inflation Calculator,” updated Mar. 14, 2022, accessed Apr. 5, 2023, https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1867?amount=0.75

- Bernard E. Powers, Black Charlestonians: a social history, 1822-1885, (Fayetteville, AK: University of Arkansas Press, 1994), 127.

- Powers, 127-128; Ruth W. Cupp, “Longshoremen, family names go hand-in-hand,” The Charleston News and Courier, Sept. 14, 1989, Newsbank, 2.

- “Strike Amongst the Wharf Employees,” Charleston Tri-Weekly Courier, Feb. 27, 1868, Gale Primary Sources.

- Powers, 133.

- Eli A. Poliakoff, “Charleston’s Longshoremen: Organized Labor in the Anti-Union Palmetto State,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine, 103, no. 3, (Jul. 2002): 249, https://www.jstor.com/stable/27570581

- For more information about George German and Kenneth Riley’s role in the ILA, read Poliakoff’s “Charleston’s Longshoreman.”

- “News Release,” 12.

- Alina Selyuhk and Andrea Hsu, “In clash with Bernie Sanders, Starbucks’ Howard Schultz insists he’s no union buster,” National Public Radio, updated Mar. 29, 2023, accessed Apr. 5, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/03/29/1166277326/starbucks-bernie-sanders-howard-schultz-union-hearing.

Image Credits

- “Negro stevedores loading stove on boat, Burwood, Louisiana.” Russell Lee. 1944. Burwood, LA. Library of Congress. Accessed Apr. 5, 2023. https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2017738230/

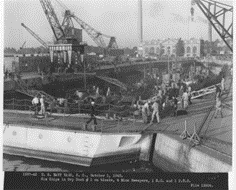

- “Six ships in Dry Dock #1.” United States Navy. 1942. Charleston, SC. Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum. Accessed Apr. 5, 2023. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:1208

- “Vendue Range.” George L. Cook. 1886. Charleston, SC. The Charleston Museum Archives. Accessed Apr. 5, 2023. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:2695