» Indigeneity Among African Americans by Mateo Mérida

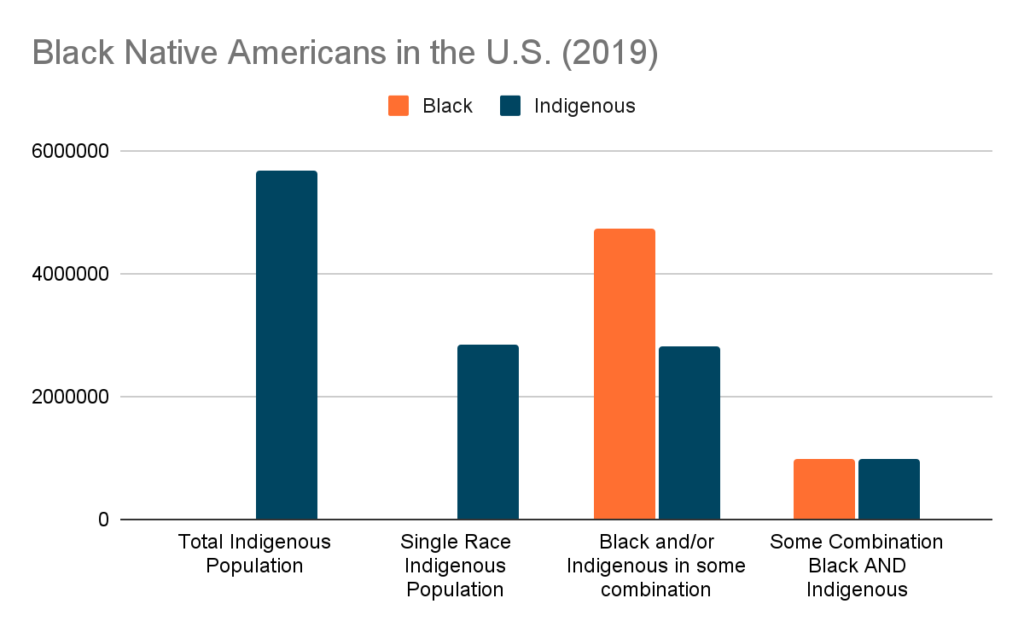

There are a wide variety of misconceptions in American history, and few communities have been subject to quite as many of these as Indigenous American people. One of the most widespread misconceptions is the discussion about who is considered Indigenous. By the predicted estimates of the US Census Bureau in 2019, 14.2% of the U.S. population was African American. Similarly, 1.7% of the U.S. population identified as having American Indigenous ethnicity. This may not appear to be highly significant until noting that 17.2% of the U.S.’s total population of 5.6 million Indigenous people were thought to have Black ancestry.

The following year the Census Bureau’s prediction was proven to be incorrect, when as much as 2.9% of the entire U.S. population in 2020 reported some combination of American Indian or Alaska Native. That is a difference of nearly 4 million Indigenous people that the Bureau had not accounted for the previous year. Until all the census data is released, it stands to reason that the Black Indigenous population in the US could be double what was predicted in 2019.

While this data may be new, the tie between Indigenous and Black American people has deeply influenced the history of both communities since the first arrival of Europeans in the Americas. Colonizers like Christopher Columbus initially sought to enslave Indigenous people, but the overall impact of settler colonialism of Indigenous American land, including violence caused by war, disease outbreaks, disruption of trade routes and food supply, etc., mean African people were forced to labor across the Atlantic Ocean in their place.

Slave holding was not exclusive to white colonizers. In fact, as a measure of assimilating to Western practices, several of the Indigenous communities of the American Southeast, such as Muskogees (native to Georgia and Alabama), Choctaws (native to Alabama and Mississippi), and Cherokees (native to the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky and Tennessee) also partook in the enslavement of Black American people, forcing them to pick cotton and other cash crops valuable to white Americans and Europeans1. The practice of enslaving Black people by the “Civilized Tribes” (referring to the Cherokees, Seminoles, Chickasaws, Choctaws, and Muskogee people Indigenous to the South East) created an entirely new perspective of Indigeneity among these tribes and nations. By the time the Civil War was over, enslaved people, who had lived in these communities for generations at that point, were rejected as members of the tribe, despite having labored for these communities their entire lives. These Indigenous Freedmen are culturally and ethnically sons and daughters of their tribe or nation, but since many tribes today use blood quantums (a measure of genetic descendancy) to determine tribalship, they are prohibited from belonging.

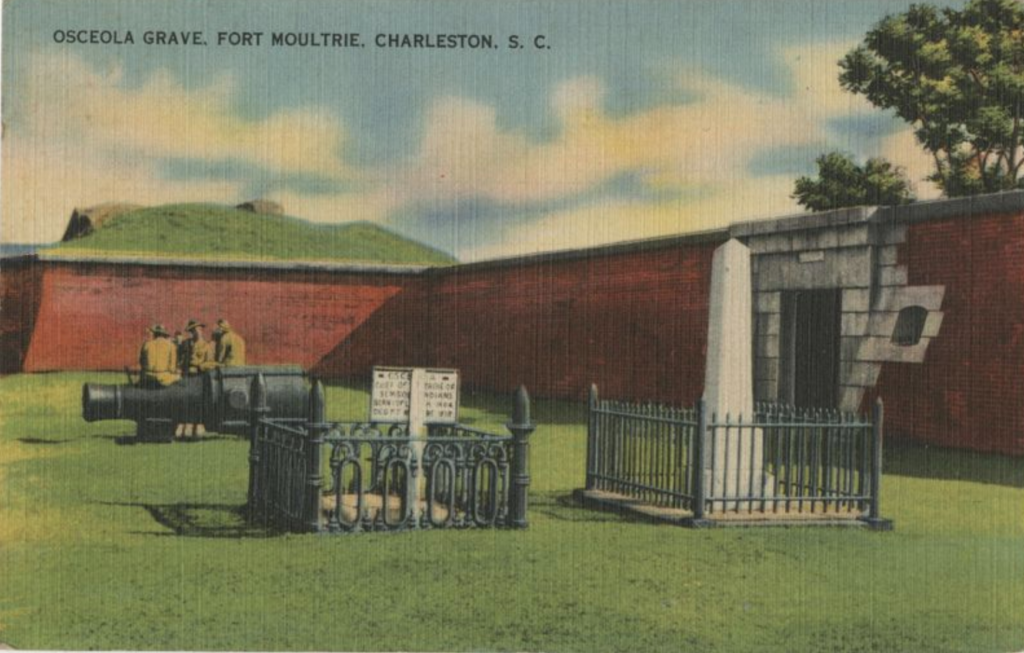

Still, many Black and Indigenous people sought refuge together, eventually building their own community in places like the Everglades in Florida, where the Seminole tribe originated. While white colonists in Georgia and Florida displaced communities of Indigenous people such as the Muskogees, enslaved African men and women self-emancipated and fled to the swamps for freedom, the Seminole Tribe, as it is understood today, came into formation. The word Seminole is thought to be derived from either the Spanish cimarrónes (runaways), or derived from yat’siminoli, meaning the free people.2 With then-President Andrew Jackson’s policy of removal in 1830, the Seminoles fought the federal government until what is known today as the Seminole Wars, which lasted until 1858. While the leader of the tribe, Osceola, was incarcerated and buried at Fort Moultrie in South Carolina, to this day, the Seminoles still have not formally agreed to peace.

The intermingling of African and Indigenous American descended people did not just show itself in political or tribal circumstances, this intersection manifested itself in legal circumstances as well. In the case of the DeReef brothers, who were the owners of a lumber mill and involved in real estate in the Charleston area, they were being taxed by the city of Charleston in the early 1800’s as free mulattoes. To negate this tax, they claimed the Indigenous American ancestry of their mother, and won their case in the Court of Common Pleas in 1823.3

While utilizing Indigenous ancestry had tangible benefits in the legal system, in late 19th and early 20th Century Charleston, it also saw more subtle influences as well. In an interview with Ruby Cornwell (who was born and raised in the height of Jim Crow era South Carolina) which discusses colorism among the Black community. Reflecting on her mother of Cherokee descent, she says “she would not have been a victim of that [colorist treatment] because, um, her mother was, was light. Her father, they were all looked like, I guess, like Cherokee Indians. They were more that type, you know. Not, a light rather than brown. A brownish.”4 In the case of Cornwell’s mother, being of mixed and Indigenous ethnicity, she enjoyed a better treatment because she was not considered dark skinned in Charleston at a time when colorism in the Black community was prevalent. While the DeReef brothers had real tangible benefits in being of Indigenous descent through a white supremacist government, Cornwell’s mother experienced social benefits in an oppressed Black community. In other words, in being Indigenous and Black, she did reserve subtle social privileges in being lighter complexioned where other darker skinned African American people did not.

Considering the experiences of the DeReef brothers and the Cornwell mother, there is an obvious question that arises: in two completely different circumstances, why does Indigenousness create privileges for multi-ethnic Black people? Looking at the Slave Codes of 1740, it describes a distinction between Indigenous people who are “in amity” with the government, and those who are not.5 As long ago as 1740 is even in consideration of Cornwell’s mother in the early 1900’s, laws like these show the ethos that has driven American policy with Indigenous people since before its foundation. There is a desire to “civilize” Indigenous people, and for Indigenous people to want to do so peaceably. Even considering federal government policies like Termination and Relocation, which terminated Indian Reservations and attempted to relocate them to American cities ooze this same kind of cultural erasure that American white supremacist government has driven for centuries.

In contrast, Blackness has been treated across American history as in direct opposition to American citizenship. Studying the same document, Dr. Nick Butler of the Charleston County Public Library describes “The law did not recognize them [free black people] as fully-formed citizens, however. The mere facts of their skin color and non-European ancestry created legal “disabilities” that diminished their civil rights.”6 This is a philosophy that still carries to this day, especially in regard to drug policies, mass-Incarceration, and police killings of unarmed Black people. In summation, the legal codes across American history believe Indigenous people can become citizens, but Black people cannot. For this reason, being Black and Indigenous creates privileges Blackness alone is excluded from.

To move away from the legal and cultural implications of Indigeneity in Black life, Indigeneity for Black Americans has also been seen as a source of pride. Frank Albert Young was a sports editor, historian and lecturer from Chicago, nicknamed “Ghost Green Eyes” by some, but most prominently was recognized as a labor activist. Young was also the descendant of the Lenape people. Known to many as the Delaware people, the Lenape homeland is in the New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware area, but in the process of colonization, they have since migrated throughout the U.S. In addition to his work as an activist, he also spent much of his time researching Lenape history and culture, and even enrolled himself in the Lenni Lenape Historical Society.7 Even among African American people who are not known to be Indigenous, the Civil Rights Movement also saw a lot of support for the American Indian Movement by African American people. One of the most prominent examples includes the likes of American Indigenous people such as Martha Grass of the Ponca Nation (Indigenous to Nebraska but removed to Oklahoma) being involved in Dr. Martin Luther King’s Poor People’s Campaign. Grass spoke widely about the lack of financial and educational resources available to Indigenous people and used the Poor People’s Campaign to highlight some of those issues.

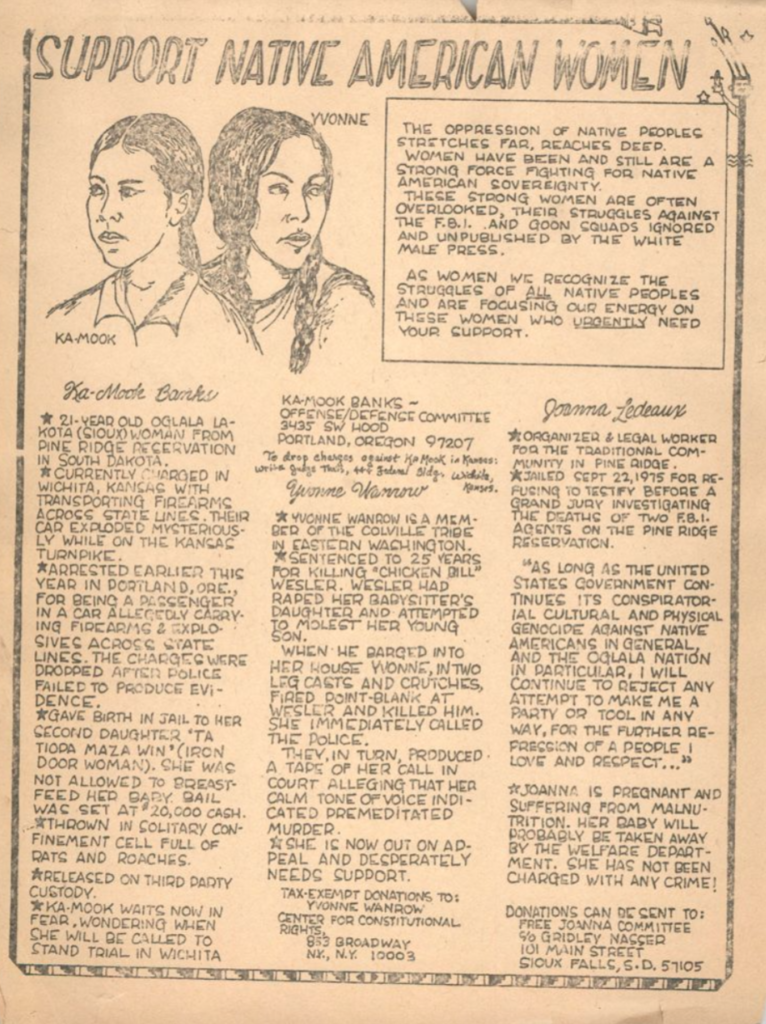

Beyond national movements like the Poor People’s Campaign, local activist Cleveland Sellers from Denmark, South Carolina was cognizant of issues relating to Indigenous people. In his collection of papers housed at the Avery Research Center from throughout his life, is one entitled “Support Native American Women.” Bernice Robinson, a Charleston native whose papers are also housed at Avery, also had a Community Action Program memorandum, which discusses the federal government, and funding policies concerning Native American Reservations.8

While many Black activists were well informed of issues pertaining to American Indigenous people, the contentious issue among Indigenous tribes and nations pertaining to the enrollment of Black people in these entities has existed since the Civil War.9 As recently as 2011, the Cherokee Nation faced widespread criticism across the U.S. for attempting to restrict the enrollment of Black members.10 That was backtracked this year, as the Cherokee Nation has since opened a path to tribal membership for people who are descendants of those enslaved by the Cherokee Nation.11 Indigeneity has a long and complex history in the United States, and its deep tie with African descended people is equally as complex. It is a conversation that has been taking place for hundreds of years and is just as nuanced now as it was when Black people were enslaved by some tribes, while being active members in others.

Sources

- Smithers, Gregory D. The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity. Yale University Press: New Haven, CT. pp 123-125.

- “Indian Resistance and Removal.” Seminole Tribe of Florida. Accessed 12/1/2021. https://www.semtribe.com/stof/history/indian-resistance-and-removal

- Mayo, Georgette. “DeReef Court and Park collection finding aid.” Avery Research Center: DeReef Court and Park Collection. March 2014. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://findingaids.library.cofc.edu/repositories/3/resources/223

- Cornwell, Ruby. “Oral history Interview with Ruby Cornwell.” Avery Research Center: Avery Research Center Oral Histories. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. Pp 16. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23389

- McCord, David J. ed. The Statutes at Large of South Carolina. Vol. 7, Containing the Acts Relating to Charleston, Courts, Slaves, and Rivers. Columbia, SC: A.S. Johnston, 1840, p. 397. Pp 5. Accessed December 1, 2021. www.teachingushistory.org/pdfs/Transciptionof1740SlaveCodes.pdf

- Butler, Nic. “Defining Charleston’s Free People of Color.” Charleston County Public Library. February 7, 2020. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/defining-charlestons-free-people-color

- Avery Research Center: Frank Albert Young Papers. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. Box 6, folder 1.

- “Community Action Program Memorandum No. 38.” Avery Research Center: Bernice Robinson Papers, 1920-1989. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. 1996. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:99923

- Smithers. “Ch. 7, Cherokee Freedmen” in The Cherokee Diaspora.

- Kellogg, Alex. “Cherokee Nation Faces Scrutiny for Expelling Blacks.” All Things Considered. NPR. September 19, 2011. https://www.npr.org/2011/09/19/140594124/u-s-government-opposes-cherokee-nations-decision

- Walker, Mark. “Cherokee Nation Addresses Bias Against Descendents of Enslaved People.” The New York Times. February 24, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/24/us/politics/cherokee-nation-black-freedmen.html

Image Notes

- I made this graph with the data from “Selected Population Profile in the United States.” US Census Bureau. 2019. Accessed November 30, 2021. This weblink will yield the same applications and settings I applied in order to create the raw data provided in the graph I created. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=S0201&t=004%20-%20Black%20or%20African%20American%20alone%3A005%20-%20Black%20or%20African%20American%20alone%20or%20in%20combination%20with%20one%20or%20more%20other%20races%3A006%20-%20American%20Indian%20and%20Alaska%20Native%20alone%3A009%20-%20American%20Indian%20and%20Alaska%20Native%20alone%20or%20in%20combination%20with%20one%20or%20more%20other%20races&tid=ACSSPP1Y2019.S0201&hidePreview=true.

- “Osceola Grave, Fort Moultrie, Charleston, SC.” College of Charleston Libraries: Leah Greenberg Postcard Collection. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. 2013. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:86204

- Avery Research Center: Frank Albert Young Papers. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. Box 6, folder 1.

- “Support Native American Women.” Avery Research Center: Cleveland L. Sellers, Jr. Papers, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. 2016. Accessed November 30, 2011. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:102886