» Democracy as a Façade (Part 2) by Mateo Mérida

This is part two of a two part series that is examining the experiences of African Americans and democracy. See part 1 here

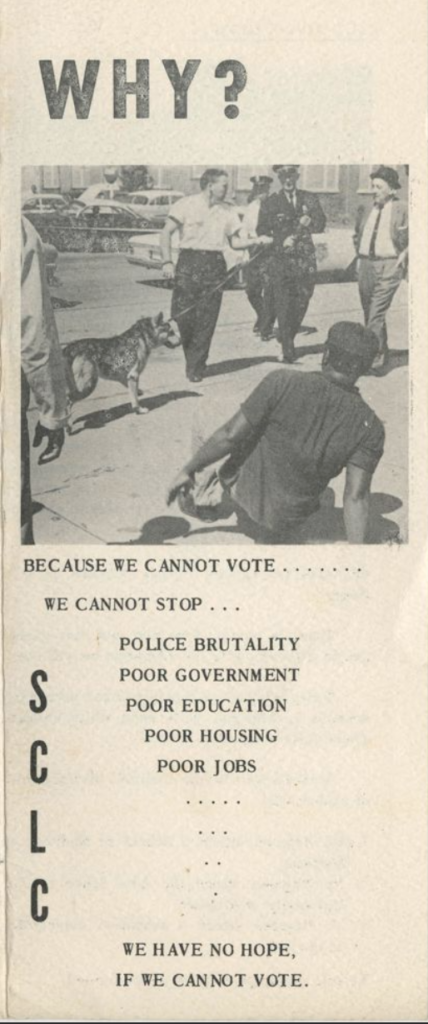

This outlook is put on full display in some of the information distributed by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). One such pamphlet reads “Because we can’t vote, we cannot stop police brutality, poor government, poor education, poor housing, poor jobs.”1 For many Black Americans, the democracy that was supposed to be upheld by the 15th Amendment possessed the tools to create the change in American society that they needed to improve their status as marginalized people. However, the goal posts had been moved in so many ways and so many times that they were never permitted to use these tools. By giving Black people the means to vote unconditionally, the SCLC believed it could uplift the entirety of the African American community.

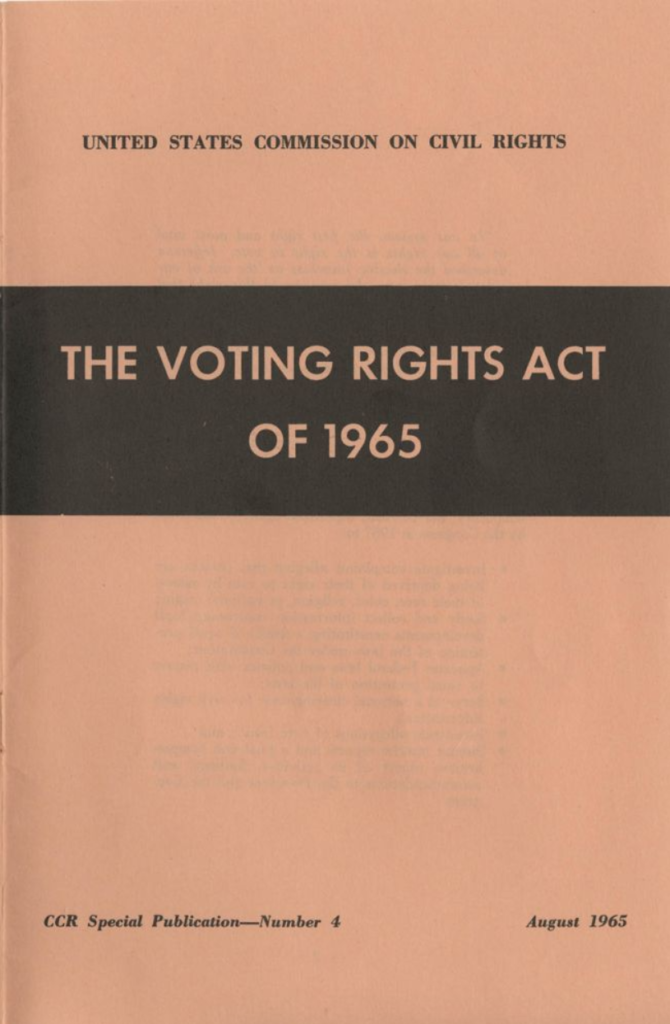

In 1964, the passage of the 24th Amendment made the practice of poll taxing illegal. The following year (merely four months short of a full century after the ratification of the 13th Amendment), then President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, which fully abolished racial discrimination regarding voting. It also suspended literacy tests in several jurisdictions, before being completely abolished in 1970. The efforts of the Civil Rights Movement had proven successful in securing Black voters’ position in American democracy. According to figures quoted from the 1970 U.S. Census, 61% of Charleston’s Voting age Black population was registered to vote, in contrast to 48% of white Charlestonians.2 For a city in the Deep South to have such a high figure of registered voters, given the constant threat of violence and sizeable legal barricades, these figures are indicative of the hard fought battle for Black Americans to participate in the democratic process as they were promised over 150 years ago.

These numbers also are indicative of a fundamentally identical battle from the other side of the Civil Rights Act: keeping the vote. In the last fifty years, one of the most successful mechanisms in stripping Black people from voting has been the impact of mass incarceration and the War on Drugs. Given the successes of the Civil Rights Movement, conservatives such as Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan proliferated drug policies to target entire communities serving as political rivals of Republican candidates and conservative interests, and this overwhelmingly meant poor Black Americans. These drug policies—a boon of the crack epidemic of the 1980’s-1990’s—have been overwhelmingly successful in incarcerating African American people at rates far beyond their proportion of the American population as a whole.3 People convicted of felonies, such as drug dealing and trafficking, are legally prohibited from voting in several states, notably in the South. For comparison, there are 10.3 million people living in prisons globally. 2.2 million are in the United States. The country with the next largest prison population is China with 1.6 million, despite having more than four times the total population of the U.S.4

In addition, in 2020 presidential primaries and caucuses, certain districts across the country in predominantly Black and Latine communities closed their doors for the purposes of voting because of the pandemic. As a consequence, in the 2020 primaries in Georgia people of color waited for an average of 51 minutes in line to vote, while white people waited 6 minutes comparatively.5 Similarly, voter ID laws, much like poll taxes, create additional barriers to voting, that if you don’t have the time, the money, or the documents to get a voter ID, then you cannot vote. Voter ID laws overwhelmingly impact people of color.6

Consider a scenario where a person working a minimum wage job needs to schedule an appointment at the DMV (which is only open during general workday hours of 8am-4 pm), to pay the $25 for a new driver’s license to satisfy the voter ID requirement (4 hours of work at $7.25 after tax), and then plan to sacrifice 4 hours of the work day, just in case it happens to be a particularly busy day at the DMV (God willing it’s only busy and nothing goes wrong, taking up more time). Suddenly, in the wake of paying other bills and not using up rare sick or vacation days, or potentially putting your job on the line in unpredictable DMV circumstances, acquiring a voter ID card is a lot more difficult than just showing up. Then consider that voting is always on a Tuesday, presenting the exact same issues as acquiring a voting ID card does all over again.

Then factoring in incarceration rates, long wait lines, and that most people of color are restricted to wage labor, this is a concerted effort to silence the vote of people of color.

Democracy is thought to be as American as apple pie, but there is a profound argument to be made that so is voter suppression. As time grows farther and farther away from the Civil War and Civil Rights Movement, our ideas of whose voice is worthy of being heard has not changed. Imperative progress has been made in making the U.S. the representative democracy that it strives to be, but as long as it puts methodically prejudiced limitations on who is permitted to participate in the voting process and who is not, it will always fall short of that American Dream.

Sources

- “‘Why?’ Pamphlet.” Avery Research Center: Bernice Robinson Papers, 1920-1989. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. April, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:99888

- “Voting Registration Statistics for Charleston County, U.S. Census 1970.” Avery Research Center: Septima P. Clark Papers, ca. 1910-1990. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. February, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:93090

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. The New Press: New York, NY. 2012.

- Walmsley, Roy. “World PRison Population List eleventh edition.” World Prison Brief. Institute for Criminal Policy Research: London, UK. 2015. https://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/world_prison_population_list_11th_edition_0.pdf

- Rodden, Jonathan. “Expert Report of Jonathan Rodden, PhD.” Stanford, CA. August 31, 2020. pp. 4. https://www.democracydocket.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Expert-Report_Long-Lines.pdf

- American Civil Liberties Union. “Oppose Voter ID Legislation – Fact Sheet.” American Civil Liberties Union. Accessed December 9, 2021. https://www.aclu.org/other/oppose-voter-id-legislation-fact-sheet

Image Credits

- “‘Why?’ Pamphlet.” Avery Research Center: Bernice Robinson Papers, 1920-1989. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. April, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:99888

- “The Voting Rights Act of 1965.” Avery Research Center: Bernice Robinson Papers, 1920-1989. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. April, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:98805

- Hiltzik, Michael. “Column: Don’t give Coca-Cola and Delta too much credit for stance on Georgia voting law.” Los Angeles Times. April 6, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2021.https://www.latimes.com/business/story/2021-04-06/georgias-voting-law-delta-coke