» Democracy as a Façade (Part 1) by Mateo Mérida

This is part one of a two part series that is examining the experiences of African Americans and democracy

The Civil War played a huge role in the grand context of American history. Beyond being the only war in world history explicitly fought for the purposes of ending slavery, it is also the war that gave citizenship to millions of people who were held in bondage just a few years prior. Despite how the United States has historically made the right to vote a fundamental aspect of what it means to be an American citizen, American democracy has been beleaguered with a plethora of caveats regarding who is or is not eligible to vote. Even to this day, it has been African American citizens who have been methodically inhibited if not fully denied the ability to participate in the vote.

The disenfranchisement of the participation of Black Americans from American Democracy really begins to take shape in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. Within three years of the war’s end, the Reconstruction Amendments ended slavery, gave citizenship to all people born on American soil, and gave all of those (initially male only) citizens the right to vote.1 For the first time in American history, Black Americans were explicitly protected in federal law with the right to vote.2

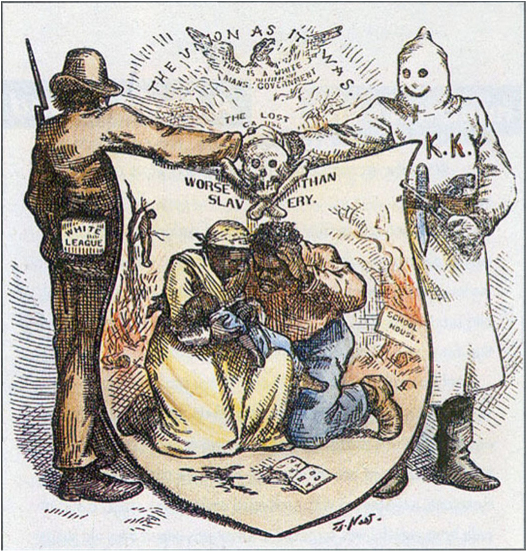

As much of a milestone as these Amendments were for American Democracy, the pushback created by white Southerners quickly shattered what gains had been made for Black people and their ability to vote. With the end of the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was founded in Tennessee in 1865, as a terrorist group looking to consolidate white supremacy in a region where white Americans interpreted the inclusion of Black Americans into the voting booths, political offices, and citizenship, as an existential threat to white hegemonic social order. While the Klan itself dissipated in its first iteration in 1877, that same year also marks the departure of Union troops from the South. As might be expected, violence increased in the federal government’s military absence. From 1882-1968, as many as 4,743 people were lynched in the U.S., 73% of which were African American.3 The alleged ‘last’ lynching in American history was in 1981.4 Of course, these figures do not convey the prevalence of other acts or threats of violence, rather the number of Black people killed in high spectacle, extralegal homicides.

In the 1930’s, the KKK returned and lingered into the 1940’s, before resurging again in the 1950’s, with lasting membership into the present day. For some younger people, the threat of violence became a real and tangible fear with the reintroduction of the Klan into daily life. Lucy Patterson Frinks was born and raised in Abbeville, South Carolina, and eventually would go on to integrate Abbeville High School. In the Oral History project Somebody Had to Do It, Frinks reflects on some of the influences that helped prepare her to integrate AHS. In particular, she recalls her mother’s fearlessness as an active voter in Abbeville, South Carolina. She says “My mother always was able to vote. I’ve never known a time when she didn’t go to vote and she took us with her. And sometime [sic] she would say, ‘Hold on to my leg.’ I didn’t know that we were in danger by her going to vote.… I want to say the first time I recognized fear, not really being sure what that was was when there was a Klan march through our community.”5

There are two elements that demand to be discussed in Frinks’ recollection. First, the threat of violence poised by the Klan was plainly visible to all Black people, and age did not matter in the ability of Black Americans to recognize such. Second, the threat of violence was not enough to deter Black people from voting, at least in the case of Frinks’ mother. As Frinks describes, though she was able to recognize the terrorist threat of the Klan, she saw voting as a duty that her mother was obligated to fulfill. Violence or the threat of it did not stop Black people from filling the ballot boxes.

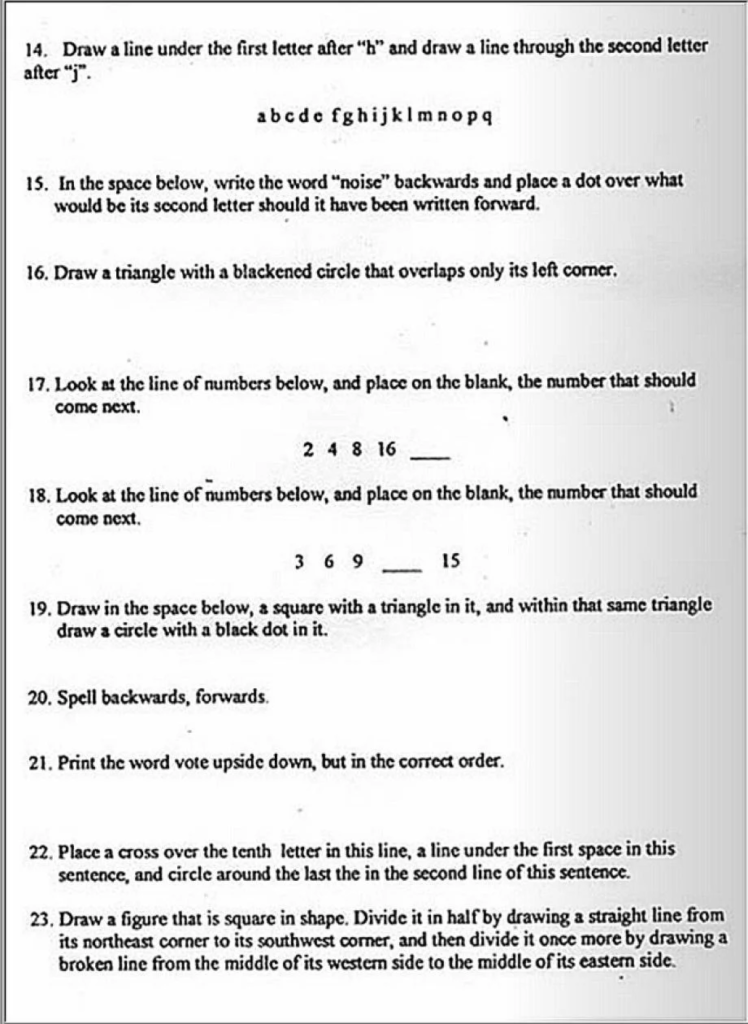

It is for this reason that fully legal practices were put in place to inhibit the ability of Black citizens to vote. One of the methods to inhibit voting by Black citizens—and only Black citizens—was the requirement of a literacy test. Instead of a language arts tests one might envision for an 8th grade reading level targeted to a wide audience, much like most newspapers are written to be, these were tests that were made nearly impossible to pass. Full of vague wording, and trick questions, literacy tests were a deliberate mechanism to prevent Black people from passing and therefore being unable to vote entirely.

Another hurdle thrown into the mix was a poll tax. This tax was implemented as a fee necessary to vote in elections, which all voters in certain states were required to pay. While some states outside of the South also implemented poll taxes, every one of the Confederate States which seceded against the Union would go on to implement a poll tax for a period after the Reconstruction period. With this implementation, poor families—who were Black, in reliable quantity—were restricted from voting, by consequence of being unable to pay the tax in order to do so.

By the mid-20th Century, grassroots activist movements were well underway with a focus on shattering the prejudiced voting laws that characterized voting in the South. One of these activists was J. Michael Graves. Born and raised in Charleston, South Carolina, much of Graves’ professional career was as a teacher. He also was involved in the Progressive Democratic Party, working diligently in pushing for a Voting Rights Act, work he would continue to do upon becoming the Chairman of the executive committee of the NAACP.6 When considering all of the missions of the Civil Rights Movement—ending segregation, quality education, ending police violence, etc.—it may be somewhat surprising to consider that voting rights seemed to dominate so much of Graves’ political career, given the scope of so many of these problems. Yet, in the eyes of many Black Americans in the Civil Rights era, a Voting Rights bill would help to address all those issues.

Check back next week for part two we learn about additional ways that the right to vote is being endangered.

Sources

- U.S. Const. Amends. XIII, XIV, XV.

- This is not to imply that this is the first time Black citizens were allowed to vote completely. In states like New York, Black voters were prominent in states like New York, until movements led by the likes of Martin Van Buren actively stripped New York voters of this right. Gosse, Van. “NY’s history of blocking Black votes.” New York Daily News. March 2, 2021. Accessed December 2, 2021. https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-oped-nys-history-of-black-voter-disenfranchisement-20210302-5lndjww6gnhw7bw5iv67a6darq-story.html

- Johnson, C. W. “Lynching Information.” Tuskegee University Archives Repository: Collection: Lynching Information. Tuskegee University: Tuskegee, Alabama. November 16, 2020. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://archive.tuskegee.edu/repository/digital-collection/lynching-information/

- Gore, Leada. “‘Last Lynching in America’ shocked Mobile in 1981, bankrupted the KKK.” Alabama Local News. April 26, 2018. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://www.al.com/news/2018/04/last_lynching_in_america_shock.html

- Patterson Frinks, Lucy Brenda. “Somebody Had To Do It Collection: Interview with Lucy Brenda Patterson Frinks.” Avery Research Center: Somebody Had To Do It. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. August 8, 2011. Accessed December 7, 2021. Pp 17. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:100503

- Graves, Michael. “Oral History with James Michael Graves” Avery Research Center: Avery Research Center Oral Histories. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. May, 2009. Accessed December 7, 2021. Pp 20. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23393

Image Credits

- Silverbrook, Julie, iCivics. “The Ku Klux Klan and Violence at the Polls.” Life Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness: Chapter 8: 1860-1877. Bill of Rights Institute: Arlington, VA. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-ku-klux-klan-and-violence-at-the-polls

- Onion, Rebecca. “Take the Impossible ‘Literacy’ Test Louisiana Gave Black Voters in the 1960s.” Slate Magazine. June 28, 2013. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/06/voting-rights-and-the-supreme-court-the-impossible-literacy-test-louisiana-used-to-give-black-voters.html