» Black Hair and Coerced Conformity by Mateo Mérida

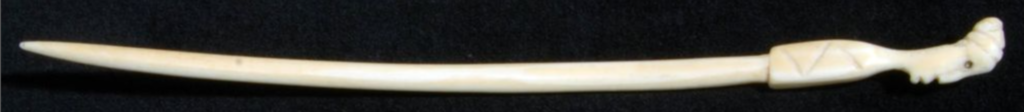

Hair has held an important place in the conversation of assimilation, conformity, and oppression throughout the African Diaspora. Regarding the figure to the left, given the way that the hair of this figure is organized being wrapped around the lower part of the figure’s head, with details towards the back of the head reminiscent of a kind of braiding, coupled with the curved shape of the figure’s head, it has been determined that this figure is a Mangbetu woman, who are native to northeastern Democratic-Republic of the Congo Taking the top of this ivory hair pin (above).

Practices like hair care and style were not completely lost in the African Diaspora, and instead were often transmitted generation after generation among African American families. Unfortunately, that does not go to imply that those same practices with hair were embraced by the dominant party of a racial caste system, which regularly policed non-European or non-Western cultural practices like hair. African hair care and practices were devalued in comparison to the hair care and styling practices of Europeans.

This effort to relegate acceptable and unacceptable forms of self-expression is clear in the lived experiences of Felder Hutchinson. Throughout his oral history, he regularly described people by their hair and eye color, while pointing out that hair color had a tangible influence on daily life. He explained that “a lot of that passing for white was the fact that they had had an education, and the only thing that was held against them was they were black… and so they were hiring people and [sic] say in New York and Connecticut with blue eyes and blond hair and they went right on.”[1] Part of being eligible for jobs that required a higher education in the early 20th Century was contingent on being white, or—in the case of Black people—in displaying whiteness. As a result, being white-passing was highly valuable in an environment where Blackness or being a Black person was treated with discrimination and contempt.

Experiences like these were not restricted to the Northeast, but were common place across the country. Ruby Cornwell recalled a young woman named from her early childhood in South Carolina. She described Lizzy as having “the long brown hair” and “looked like a white girl.”[2] Here, Cornwell is not describing that was necessarily an African American woman, but rather that she appeared to be a white woman, while implying that she actually was not. In her own words, her hair, in its straightness and color had a lot to do with what made Lizzy white-passing in Cornwell’s eyes. Cornwell’s description places an emphasis on this display of whiteness as a defining characteristic of how she remembers who Lizzy is as a human being.

In the mid to late 20th Century, the Black is Beautiful movement would go on to challenge the near universal acceptance that Western standards of hair care and style had enjoyed throughout American history. The hair pick from t he Joseph A. Towles Artifact Collection on the right—with a Black Power fist and a peace sign in its center—would have become a very common sight in the 1960’s and 70’s, in a widespread effort to celebrate the uniqueness of Black hair.

Without question, one of the single most visible icons of the later Civil Rights era, who was very well known for her afro was Angela Davis. Of course, Angela Davis’ hair was not the reason that she was so well known in the public sphere, as she was a very high-profile member of the Black Panther Party. Still, everywhere that she was seen, her afro was seen as well. With the combination being seen on posters, on pins as seen in the artifact from the Walter Pantovic Artifact Collection, on the news, and in the newspapers, as well as being such a well-respected Black activist, many people sought to emulate her. In the oral history of Lucy Brenda Patterson Frinks, Frinks describes explicitly that Angela Davis was a person that she sought to emulate in more ways than one. She elaborates “I saw Angela Davis and she was an inspiration to me kind of growing up. I wore my hair in a big bush and I just saw her as a woman who was true to her resolve.

Fighting to make the community better and not afraid to say that she was black, she was proud, and that we are the masters of our destiny.”[3] In Finks’ eyes, the way that Davis wore her hair was a direct reflection of the ethos of self-determination that Davis imbued. To be like Angela Davis in her celebration of Blackness, that meant wearing your hair like Angela Davis, which totally rejected the ways that Black Americans had been historically conditioned to view and wear their hair.

There is much to be said about the role which hair—in all the ways it has been accepted, styled, and rejected—plays in dichotomies of oppression at large. To this day, it still is a point of contention, as people in authority attempt to confine what is considered professional or informal to Western hair standards, while many African American people continue to express themselves and practice the traditions rooted long and far before there ever was a United States to consider.

[1] Felder Hutchinson, Drago, Edmund L., and Eugene C. Hunt. ‘Oral History Interview with Felder Hutchinson.’ Avery Research Center: Avery Research Center Oral Histories, 1985. Pp 15. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23398.

[2] Ruby Cornwell, Drago, Edmund L., and Eugene C. Hunt. ‘Oral History Interview with Ruby Cornwell.’ Avery Research Center: Avery Research Center Oral Histories, 1981. Pp 6. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23389.

[3] Frinks, Brenda, Benetta Standly. ‘Somebody Had To Do It: Interview with Lucy Brenda Patterson Frinks.’ Avery Research Center: Somebody Had to Do It. 2011. Pp 16. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:100503.