» Archive Spotlight: Malcolm X Liberation University by Mateo Mérida

Activism is one of the most defining characteristics of the 1960’s in the United States, and much of that has been organized by individuals from 15 to 29 years of age and who organized inside and outside of educational institutions. While students were prominent participants of the March on Washington, the Sit-Ins, and draft card burnings, students also protested and demonstrated to change higher education itself. In North Carolina, such student activism led to the founding of an Independent, Pan-Africanist college called the Malcolm X Liberation University (MXLU), which aimed to change the way other schools in the North Carolina Research Triangle taught and educated Black students.

Well before the MXLU’s founding, Duke University was segregated, and prohibited the enrolment of Black students. That changed in 1961 as an anti-discrimination policy was passed by the college’s board, with some of the first Black students matriculating in 1963. Simply admitting Black students however, did not mean the end of structural racism. Many Black students at Duke were highly frustrated by the lack of representation they encountered with the school’s faculty and curriculum. At the behest of Black students, in November 1968, a committee was formed to create a Black studies program, at a time when the rising number of Black students enrolling in the University showed a rate of 15% of those students not finishing their freshman year.1

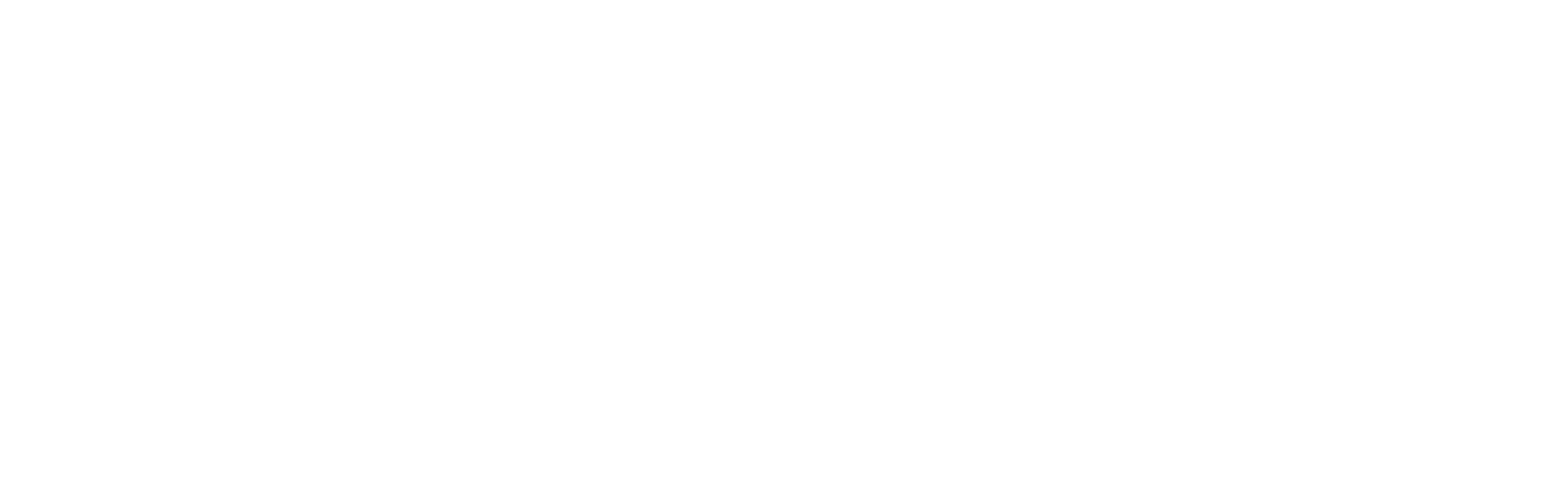

This tension, coupled with several others, such as the lack of a Black advisory board, or a Black dormitory to accommodate students, in addition to the regular harassment Black students faced by campus police, an abundantly low admittance of Black students ultimately boiled over when as many as 50 members of Duke’s Afro-American Society occupied the Allen Administration Building on February 13th, 1969. With possibly as many as 1000 onlookers and 200 white students barricading the building from police entry, the incident turned violent as police tear gassed and injured as many as 20 students. While Duke would go on to implement a Black studies program, this episode showed these Black students that the university was not willing to accommodate them in all the ways they needed, thus many dropped out, and founded the Malcolm X Liberation University.2

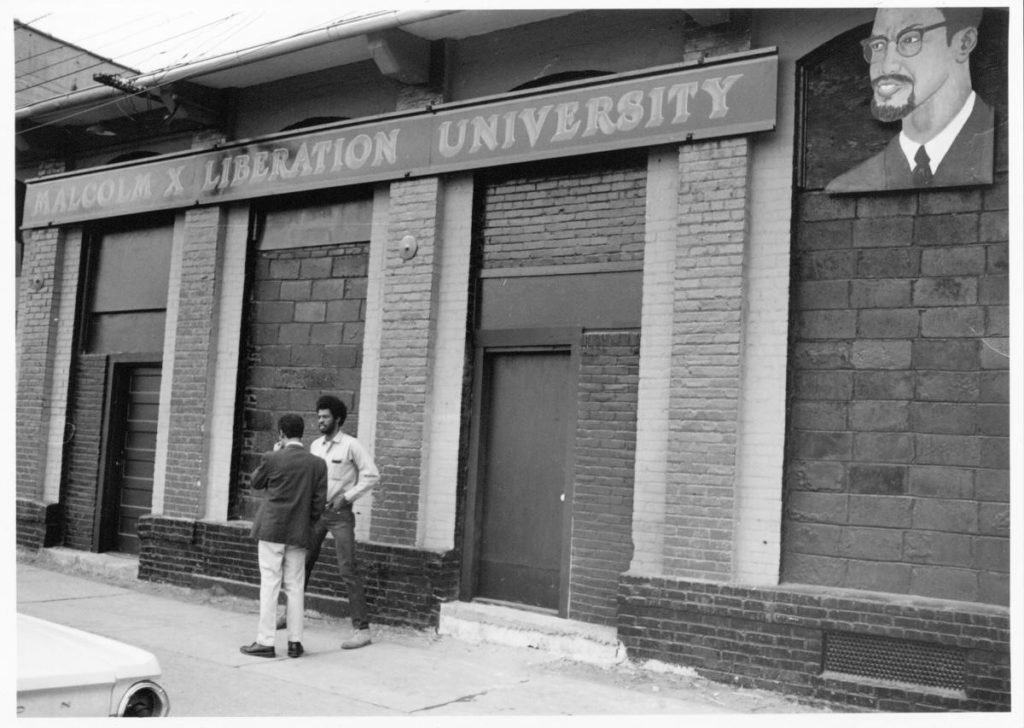

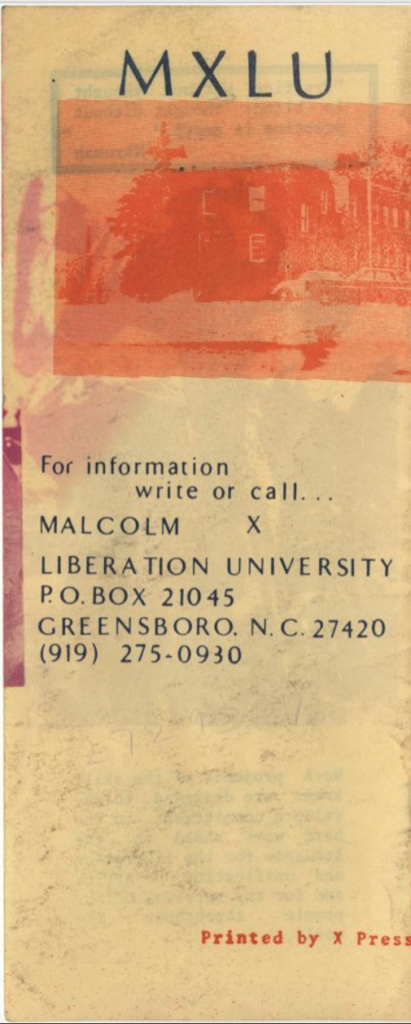

Much of what is known about MXLU is a direct result of the Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. papers housed at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. Sellers is one of the most prominent figures of the civil rights movement in South Carolina. He was born in Denmark, South Carolina, became a prominent student activist and organizer, and then later a professor of historical education. He was also the only person arrested—wrongfully—for being a protestor at the Orangeburg Massacre in 1968. While the connection that he shares with the MXLU is not clear, he kept hundreds of pages of documents related to the school’s foundation, and day to day operation. According to the documents in Sellers’ collection, the school existed as a three-year Black studies program, with a wide variety of courses which included African and Black American history, economics, Swahili, Hausa, and Yoruba language. The plan was that students in the first two years would take prerequisite courses, and as they advanced into their third year, they would be required to teach some of the courses.3

Philosophically, “The curriculum of Malcolm X Liberation University, based on the ideology of Pan-Africanism and termed ‘Nation building’, is designed to provide technicians to serve the needs of the unified African Nation.” While the school was born out of the racialized oppression that Black students in Duke University encountered, the Liberation University had far bigger ambitions than just creating a Black Studies program. In the eyes of the students who created the program, Black studies provided an opportunity to extend an interest of students of African American issues to fitting within a much larger and international African community and liberation struggle. Teaching this idea of the global community, also meant teaching students to be active members of it, using the skills they gained in social sciences, language, and historical awareness.4

This broad and collective sense of a new community is well reflected in the involvement of people well beyond North Carolina. The members of the University consisted of the students who withdrew from Duke, as well as other NC colleges. Other members were from New York, Massachusetts, and Washington, DC.5 As the school was beginning to enroll its first students, in July of 1969, the school received 65 applicants, the majority of which came from North Carolina. The rest of the applicants came from Boston, Atlanta, Arkansas, New York, DC, and even Puerto Rico. The University also attempted to create a program to send students to Africa.6

Despite this incredibly bold vision, MXLU closed in 1973. In the master’s thesis of Brent H. Belvin, who studied the Liberation University, Belvin believes that two key reasons why it closed so quickly is directly tied to the lack of support that the university saw from Black civil rights organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Similarly, it received no support from other historically Black universities. The school was not accredited, and administrators believed “The accreditation for the University will be granted by the Black community.” The founders of the Liberation University were far more focused on building a united community of African people than they were on actively maintaining a university. As a result, the model was unstable, and the school closed a few short years after its foundation.7

This school was founded to educate Black students in studies and issues pertaining to Black people in the United States, and around the world, and was founded as a direct result of the racialized treatment these Black students faced at Duke. When the school closed, the school’s founder Owusu Sadaukai, “told people that MXLU would last only as long as it met the ‘needs of the people’ and that he would not keep it going “just because it was our thing.”8

Black students dropping out of higher education is a well-documented phenomenon, and a study by Nolan L. Cabrera finds one factor is directly tied to the fact that many white male university students do not consider race as an element of their own identities. This is significant because if they cannot understand how race is influential upon themselves, then they cannot understand how race impacts non-white people, making non-white students more vulnerable to the disadvantages they already face. Cabrera concludes that it is the responsibility of the university to challenge white preconceptions of race. Where the university exists to educate the whole person, race needs to be a part of that conversation, which is exactly what the founders of the short-lived MXLU understood and is the same battle that Cabrera documents as alive and well to this day.9

Today colleges and universities have faced accusations of being spaces of indoctrination for liberal ideology as well as not going far enough regarding diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice. The fruits of celebrating and accommodating cultural diversity came from the labor of students of color in the mid-20th Century. Without the protests, organizing, and founding of institutions like MXLU, higher education might not look very different from how it did in the 1950s.

Sources

- “Background Information on the Malcolm X Liberation University, March 1969.” Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. Collection, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Digitized Aug., 2016. Accessed March. 9, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:106787.

- Durham County Library. “Duke University Allen Building Takeover, 1969.” The Durham Civil Rights Heritage Project. Durham County Library: Durham, NC. Sept. 18, 2020. Accessed Mar. 9, 2022. https://durhamcountylibrary.org/exhibits/dcrhp/events/duke_university_allen_building_takeover_1969/.

- “Malcolm X Liberation University Curriculum Plan, 1970-71.” Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. Collection, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Digitized Aug, 2016. Accessed March. 9, 2022. Pp. 1. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:106674.

- Ibid.

- “Proposal for Malcolm X Liberation University, June 5, 1969.” Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. Collection, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Digitized Aug, 2016. Accessed March. 9, 2022. Pp. 4-5. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:106600.

- “Progress Report on Malcolm X Liberation University, July 1969.”Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. Collection, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Digitized Aug, 2016. Accessed March. 9, 2022. Pp. 1. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:102632.

- “Proposal for Malcolm X Liberation University, June 5, 1969.” Pp. 4. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:106600; Belvin, Brent H. Malcolm X Liberation University: An Experiment in Independent Black Education. NC State University Libraries: Raleigh, NC. Oct. 6, 2004. Accessed Mar. 9, 2022. Pp. 77-89. https://repository.lib.ncsu.edu/handle/1840.16/563.

- Ibid, 77.

- Cabrera, Nolan L. “An Unexamined Life: White Male Racial Ignorance and the Agony of Education for Students of Color.” Equity & Excellence in Education. Aug. 18, 2017. Accessed Mar. 9, 2021. Pp. 300-315. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2017.1336500.

Image Credits

- Durham County Library. “Duke University Allen Building Takeover, 1969.” The Durham Civil Rights Heritage Project. Durham County Library: Durham, NC. Sept. 18, 2020. Accessed Mar. 9, 2022. https://durhamcountylibrary.org/exhibits/dcrhp/events/duke_university_allen_building_takeover_1969/

- Ibid.

- “Malcolm X Liberation University Pamphlet.” Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. Collection, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Digitized Aug., 2016. Accessed March. 9, 2022. Pp. 16. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:106731