» Archive Spotlight: Commemorating Martin Luther King, Jr. by Mateo Mérida

In the United States, the third Monday of January is intended to be a day of remembrance, of reflection, and of activism, as it is recognized as Martin Luther King Day, a federally recognized holiday. As such, it is also a day that has been taken for granted by many who see it as little more than an extended weekend. It has become a day off where little regard is given for the matters which impacted Martin Luther King, Jr. For others, MLK Day is a day to reflect on the happenings of the Civil Rights Movement, with some families using the day to share personal stories of participation in the March on Washington, or watching news coverage of the Selma to Montgomery March, or to tell the story of a friend who participated in the sit-ins. At the Avery Research Center, we celebrate when Dr. King came to Charleston in 1962 to register Black Charlestonians to vote, and then returned again in 1967, speaking about the uprising in Detroit, MI, just two weeks prior to his arrival.1 Everywhere that Dr. King went, he left a very powerful memory of activism, of public engagement, and a hunger for social change.

In the reflective and active purpose of this holiday, every year removed from the assassination of Dr. King puts a lot more importance and urgency to the holiday with each passing year. It is imperative that all people who observe MLK Day remember the overwhelming number of issues that he spent his life and career fighting against.

Today, as was the case in Dr. King’s lifetime Black people throughout the United States face policies which deliberately target working class people of color to prohibit them from the ability to vote.2 Black political activists continue to be the targets of assassinations at the hands of violent mobs, white supremacists, and police officers.3 While it is illegal to actively segregate schools on the basis of race or color, a plethora of public schools are concentrated with students of color, where white students instead attend magnet, charter schools or private schools.4 Dr. King understood, these are highly deeply rooted polemic issues that necessitate radical change in order to uproot them.

The memory of Dr. King today has largely been defanged. He is popularly described as a prominent, liberalized figure of non-violence, of Protestant-Christian activism, and of a dream of racial inclusion and diversity.5

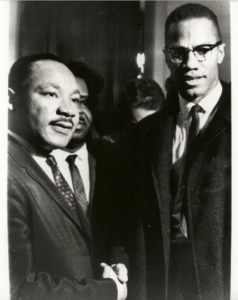

The reality is, however, that he was a radical, revolutionary socialist mobilizer and was believed to be a threat to American domestic security.6 He was regularly monitored by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.7 Dr. King had a supportive friendship with Thích Nhất Hạnh, a Buddhist monk who fervently advocated for peace during the Vietnam War, and decried American involvement in Vietnam.8 Dr. King wasn’t simply an advocate for diversity, but a fervent ally for the uplifting of all working class and oppressed people in the United States, which he demonstrated in organizing of the Poor People’s Campaign shortly before his assassination.

Dr. King did not merely say prayers, march across the South, and ask for change. Instead, Dr. King mobilized and worked alongside revolutionary organizers to advocate for and empower people to change the status quo of the United States. While he is a popular American hero today, his activism unsettled a lot of white supremacist and powerful people at every level of American government.

One might speculate that King would have deplored our current militarized police forces, thinly veiled voter suppression policies, and the deliberate defunding of “desegregated” public education. We can speculate this because these are the same unyieldingly debilitating issues he fought against during his own life. Despite the tendency to remember King’s struggle for collective human rights as a mark of the past, and the success of today, his battle is still being fought.

Martin Luther King’s leadership has left a long, and aching memory for all social activists of every ethnicity. King’s absence continues to sting. As the highly popular R&B singer H.E.R. recently sang just last year, “Ooh, times ain’t changing (Times ain’t changing) / No, people marching, no one’s there to lead (Uh) / Someone give me somethin’ to believe.”9

This MLK Day—and every day of the year—support Black business. Elevate and actively listen to Black voices. Be an advocate and an ally for the will of Black people on issues which impact Black people. Even if those ideas may seem radical—and some may be—it is a radical like MLK who fights to make those changes.

Sources

- “FLASHBACK: Dr. King visited Charleston in 1962, July 1967.” Live 5 News. Charleston, SC. Jan. 21, 2019. https://www.live5news.com/2019/01/21/flashback-dr-king-visited-charleston-july/

- Mérida-Sparling, C. Mateo. “Democracy as a Façade (Part 2).” Avery Research Center: Blog. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. December 17, 2021. Accessed January, 13, 2022. https://avery.cofc.edu/democracy-as-a-facade-part-2-by-mateo-merida/

- Fortin, Jacey. “Muhiyidin Moye, Black Lives Matter Activist, Is Shot and Killed in New Orleans.” The New York Times. New York, NY. Feb. 7, 2018. Accessed Jan. 13, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/07/us/muhiyidin-moye-dbaha-dead-black-lives-matter.html

- García, Emma. “School’s are still segregated, and black children are paying a price.” Economic Policy Institute. Washington D.C. February 12, 2020. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://www.epi.org/publication/schools-are-still-segregated-and-black-children-are-paying-a-price/

- Editors. “Martin Luther King Jr.” History.com. Published Nov. 9, 2009. Edited Jan. 11, 2022. Accessed January 12, 2022. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/martin-luther-king-jr

- Sturm, Douglas. “Martin Luther King, Jr., as a Democratic Socialist.” The Journal of Religious Ethics. Vol. 18, 2. Fall, 1990. pp 79-105. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40015109.

- “Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).” The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Stanford University: Stanford, CA. https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/federal-bureau-investigation-fbi

- Thich Nhat Nanh. “In Search of the Enemy of Man (addressed to (the Rev.) Martin Luther King).” In Nhat Nanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien. Dialogue. Saigon: La Boi, 1965. P. 11-20. Cited from Schladweiler, Kief. “King’s Journey: 1964-April 4, 1967.” African-American Involvement in the Vietnam War. New York, NY. https://www.aavw.org/protest/king_journey_abstract09.html

- H.E.R. “Bloody Waters.” Back of My Mind. RCA Records: New York, NY. June 18, 2021.

Image Credits

- “Martin Luther King, Jr. Sitting on Rocking Chair.” Avery Research Center: Septima P. Clark Papers, ca. 1910-ca. 1990. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. Digitized February, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:100499.

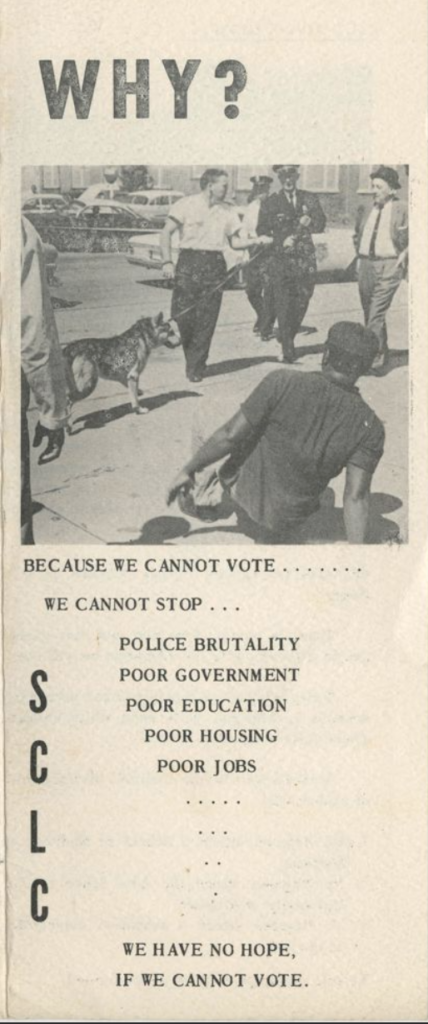

- “‘Why?’ Pamphlet.” Avery Research Center: Bernice Robinson Papers, 1920-1989. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. Digitized April, 2016. Accessed December 7, 2021. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:99888.

- “Photograph, Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.” Avery Research Center: Charleston Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Papers, 1920-1995. College of Charleston, Charleston, SC. Digitized November, 2011. Accessed January 13, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:118826.