» Anti-Apartheid in the United States by Mateo Mérida

After the peak of the US Civil Rights Movement, many African American activists interpreted their domestic pursuit of civil rights as inherently tied to movements in Africa. In the mid-twentieth century, African Americans became vocal members of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, because of the parallels they saw with their own struggles in the United States.

The parallels between the US and South Africa were obvious. Black Americans sympathized with the alienation of Black Africans in a hegemonically white society, the poverty of Black people in each place, and the practice of legal segregation known as apartheid. While the Jim Crow variation of apartheid segregation in the American South was implemented in the late 1800s, apartheid in South Africa, which was modeled in part after it’s US counterpart, was relatively new, becoming legally permissible in 1948.

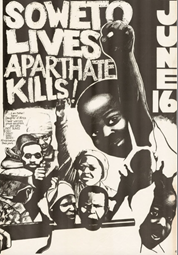

The anti-apartheid movement was propelled to the forefront Black American concern with the Soweto Uprising of 1976. A new policy prohibited African languages as a subject of education, in favor of Afrikaans (the Dutch derivative language spoken by white, non-Anglo South Africans, known as Afrikaaners) and English in the classroom. This policy, coupled with the practice of segregated education in South Africa overall, became the push for students in the outskirts of Johannesburg to walk out from classes, staging one of the largest protests in South African history. One student described “Our parents are prepared to suffer under the white man’s rule. They have been living for years under these laws and they have become immune to them. But we strongly refuse to swallow an education that is designed to make us slaves in the country of our birth.”1 Wordage like this, alluding to the disenfranchisement, enslavement, and oppression of Black South Africans resonated deeply with Black people in the US. Given the poor quality of segregated education and the history of slavery in the US South by the hands of white oppressors, the Soweto Movement put the practice of South African apartheid on full display to the world, and created an onslaught of dissent from Black activists globally, namely in the United States.

Black political organizations made no mistake of the importance of South Africa to the larger struggle for Black Liberation. One such organization, the All African People’s Revolutionary Party (AAPRP) explained that “Nowhere is the struggle for freedom more arduous, more painstaking, more long-range, nor more crucial than in the state of South Africa, the lynch pen of white supremacy in Africa.”2

The AAPRP was by no means the only institution that saw the importance of South Africa in global African struggle. Institutions like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) affirmed these issues as well, and saw the necessity to support Black South Africans in any way possible. To accommodate this stance, the NAACP officially adopted a policy of placing an arms embargo and economic sanctions on South Africa, advocating for the withdrawal of US corporations from the region.3

While American Black organizations began to organize actions to defeat South African apartheid, individual activists began to take measures as well. The Russell Press in London manufactured a poster, which was a letter written to the prime minister of South Africa. The letter describes the South African government’s comfort with detaining popular political figures without trial, such as that of Nelson Mandela, who was one of the most prominent activist figures in South Africa, and the world over all. Mandela would be held in prison for twenty-seven years. In the letter, the final line of the letter writes “When will you end political detention and give South Africa a more human face?” After the end of the letter, after the writer’s signature, a caption reads “Now you write one,” pushing the reader to write to the prime minister to push for the release of political prisoners, like that of Nelson Mandela, who were arrested because of their decrying of the apartheid system.4

James E. Campbell, was another activist who used his skills to subvert apartheid. Born and raised in Charleston, South Carolina, Campbell spent several years as an educator in Tanzania. As a long standing advocate of educational equality, Campbell participated in educational workshops to teach students about the apartheid system, and what they can do to advocate for change. Campbell’s students had opportunities to meet with two Black political parties in South Africa, which enabled Campbell’s students to understand the apartheid system, and find ways to pressure the South African government to abolish apartheid.5

By the mid 1990s, apartheid would be abolished in South Africa. Nelson Mandela was released from prison for his anti-apartheid activism in the February of 1990, and immediately created connections with Black American civil rights organizations. The NAACP has hosted an annual convention of all of its branches, and often has prominent figures come to attend. Planning for the convention in 1994, the NAACP describes “Mandela attended the 1993 convention and has maintained ongoing links with the NAACP during the historic South African elections. Development of a broad-based U.S. constituency for Africa will be among related agenda items at the convention.” That relationship became all the more powerful the year following 1993, because Nelson Mandela became the first Black head of state of South Africa, winning the first free democratic election for the presidency in 1994. Even beyond the apartheid era, the relationship between Black Americans and South Africans is mutually supportive. To this day, in the United States and South Africa, Black people face a barrage of social issues, like poverty, environmental racism, and government suppression and neglect, and continue to look to each other to pursue lasting solutions.6

Sources

- Quoted in Mwakikagile, Godfrey. South Africa in Contemporary Times. New Africa Press: Pretoria, South Africa. 2008. pp 89.

- “South African Embassy.” Avery Research Center: Cleveland L. Sellers, Jr. Papers, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC n.d. Accessed Nov. 10, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:102837

- “North Carolina Conference of Branches NAACP Position on the Republic of South Africa” Avery Research Center: Charleston Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Papers, 1920-1995. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. 1978. Accessed Nov., 10, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:121117

- “Now you write one.” Avery Research Center: James E. Campbell papers, 1930-2009. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. Jan. 18, 1978. Accessed Nov. 10, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/262766

- Veal, Erica N. 85-86. Charleston’s Black Shining Prince: James Campbell and the Evolution of African American Education. Master’s Thesis. University of Charleston: Charleston, SC. December, 2013.

- “NAACP Convention Update, July 8, 1994.” Avery Research Center: Charleston Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Papers, 1920-1995. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. July 8, 2022. Accessed Nov 10, 2022. Pp 2. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:121171

Image citations

- “Soweto Lives Apathate Kills!” Avery Research Center: James E. Campbell papers, 1930-2009. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. n.d. AccessedNov 10, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/262753

- “Shell in Zuidelijk Afrika.” Avery Research Center: James E. Campbell papers, 1930-2009. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. Accessed Nov. 10, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/262761

- People’s daily World. “Apartheid: South African and U.S. Workers Say: Shut it Down.” Avery Research Center: James E. Campbell, 2930-2009. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. 1986. Accessed Nov. 10, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/262750