» All African People’s Revolutionary Party (AAPRP) by Mateo Mérida

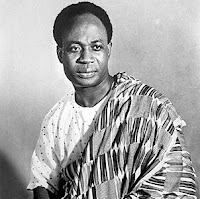

Kwame Nkrumah today carries a mixed legacy of African self-determination, and authoritarianism: of both the successes of Pan-Africanism and Socialism and their respective failures. Like the man himself, Nkrumahism—the philosophy which blended Pan-Africanism with Leninist Vanguardism formulated by Nkrumah—carries an identical legacy today. One of the most visible practitioners of Nkrumahist ideology today is called All African People’s Revolutionary Party (AAPRP), which was founded by Nkrumah in Guinea in 1966. The AAPRP continues Nkrumah’s mission of a unified African nation-state, and while it still wrestles with some of Nkrumah’s same political shortcomings, activism of the last few years has presented a possibility of such a vision becoming attainable.

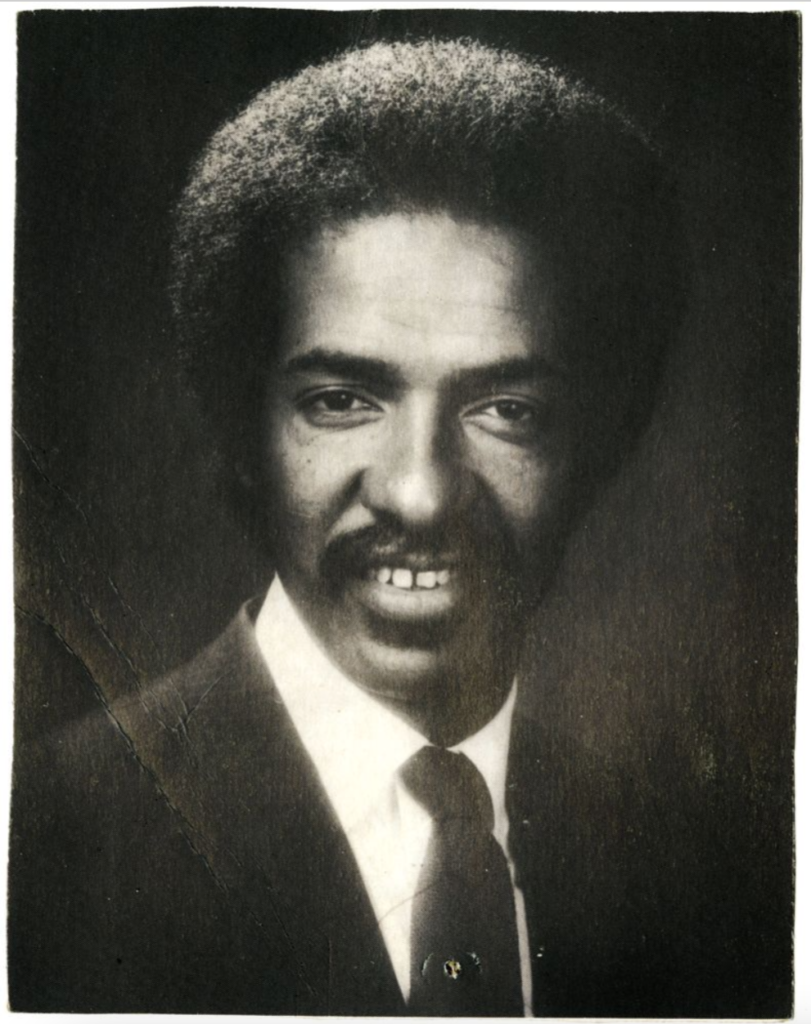

One of the most prominent collections in the Avery Research Center is the Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. collection, which houses many papers pertaining to the AAPRP. Sellers is a Black activist from South Carolina, was wrongfully arrested for participating in the protests leading to the Orangeburg Massacre, earned a doctorate in Historical education, and is a proud Socialist and Black nationalist. Sellers was an active member of the party, and is documented as a member of the Central Committee, which also included Kwame Ture (formerly known as Stokely Carmichael) who became the chief organizer of the party, centered in Conakry, Guinea.1

Much like how Nkrumah developed his political ideology as a result of his pursuit of higher education, pedagogy is a cornerstone for how the All African People’s Revolutionary Party distributed its ideology. Initially, this has been done with a practice which the party called “Workstudy,” which enrolled students to read a specific booklist, write a self-reflective essay, while participating in party activities, such as meetings or community programs. This was expected to take at least four months.2

While the AAPRP prioritized the interests of a Pan-African nation-state, the party’s perspective of liberation from imperialism and racism was not restricted only to African descended people. In the 1960s and 1970s, as the party was establishing itself in the United States, it also took great interest in American socio-political issues. The Party emphatically advocated for “Total Victory and Unconditional Support for” Puerto Rican nationalists, American Indigenous and Chicane people and their respective activist or liberational movements. As might be expected of a global ideology, it extended a similar support to Palestinian liberation from Israeli imperialism.3

The practice of widespread education, and concern with current affairs has continued to be the norm to this day. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the AAPRP branch in New Mexico has taken to using online platforms to discuss key elements of the Party’s philosophy, such as Pan-Africanism and Socialist theory. Recently, they have also uploaded a video decrying the imperialist actions of Russia in the current war with Ukraine.4

Nkrumahism was highly valuable in the way that it envisioned a broad, uniting ideology for all African people, however, that does not suggest that it did so seamlessly. The AAPRP is still active today, and has a website that they use in order to promote the party, create a base for its social media content, as well as recruit potential followers. In its current page under “About Us,” titled “What is the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP)?” section, it describes “The All-African People’s Revolutionary Party recognizes that African People born and living in over 113 countries are one People, with one identity, one history, one culture, one Nation and one destiny.” Naturally, this is a direct reflection of Nkrumahist ideology as it was created in the 1970s. With such a sweeping perspective of African people globally, this perspective becomes highly reductive of the incredible diversity of African people and African descended people. In consideration of religious, political, regional, or even traditional perspectives, as well as the wider context of slavery and African Diaspora, globally, a French-Senegalese person, an African-American person, and a Black Cuban person have all had many similarities in their interactions with racism, imperialism and other forms of Euro-centric oppression, but they are not the same experience in absolute.5

In no way whatsoever is this philosophical tension only present beyond the shores of Africa, as it directly impacted Nkrumah’s presidency in Ghana, as he regularly found opposition with the indigenous nation of Asante people who have called Ghana home for centuries. Jean Marie Allman classic text The Quills of the Porcupine: Asante Nationalism in an Emergent Ghana carefully studies this tension, concluding “But Nkrumah’s conception of national liberation, though broad enough to encompass the entire African continent, was not broad enough to encompass the demand, within his own country, for Asante autonomy. Thus the social conflict within Asante has continued to take a backseat to Asante’s broader struggles with the central government.” The Asante had such an experience with colonialism and European imperialism that they felt being one piece of a much wider African collective erased their capacity for self-determination and treated their needs as a nation as peripheral to the needs of Nkrumah’s pan Africanist vision.6

This tension within Nkrumahism, and therefore the AAPRP was not in any way unknown to the party’s organizers. They felt however, that the tensions at play were not ethnic, cultural, linguistic, or geographic, but rather surrounded religion. It argues:

Nkrumahism is a dialectical synthesis of the three africas—traditional life, Islamic Africa, and Euro-Christian Africa. Wherever Black people are in the world, we are influenced by these cultures. Nkrumahism resolves this crisis of the African conscience by uniting in one philosophical system of the quintessence of the three Africas.7

Here, the AAPRP implies that religion can continue to be an element of African identity, as long as it does not stand in the way of a unified African nation. Presumably, this belief may also likely extend to the ethnic, cultural, linguistic or geographic discrepancies as well, as long as people within the nation are able to uphold the unified national identity. Yet, this still doesn’t stand up when considering the Asante people of Ghana, and how they did not feel they should be required to, nor should be need to, sacrifice their own national interests for a larger nation they did not necessarily see themselves a part of, since most African people are not Asante indigenous people. Using the Asante, sacrificing the interests of one’s own ethnic group for a collective nation does not seem to work.

While AAPRP has not been the center of global Black thought since its foundation briefly before Nkrumah’s death, that is not to say that a collective Black consciousness or collective awareness is impossible. In 2020, the Black Lives Matter protests prompted by the murders of George Floyd and Briana Taylor were worldwide, with protests across the United States, Canada, and Europe. Yet, BLM has not only been restricted to majority white countries. One of the largest theaters for Black Lives Matter protests outside of the United States was in Brazil, which has a majority population which is at least partially African descended. While the rest of the world focused on the United States, Brazilians protested for Black Americans, as well as the unlawful and racialized murders of Black Brazilians as well.8

While the AARP has struggled to foment the Pan Africanist fervor of Kwame Nkrumah worldwide, movements like Black Lives Matter show that it is not some unattainable dream, with an idealistic view of how African descended people view their African heritage. In the time since Nkrumah’s passing, the economy has become more globalized, more and more people of color are enrolling in colleges and universities across the Western world than has yet been seen, both coupled with the internet have helped to create a more globalized view of the world that was harder to do in the 1960s. While Nkrumahism and the AAPRP have struggled to encompass a diverse and validating perspective of African descended people world wide, their mission to create a globally conscious sense of Africanness is as relevant today as it was in the 20th Century.

Sources

- “All African People’s Revolutionary Party Mailing List, November 29, 1979.” Cleveland L. Sellers, Jr. Papers, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Nov. 29, 1979. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:105161.

- “All African People’s Revolutionary Party Political Education Program.” Cleveland L. Sellers, Jr. Papers, 1934-2003. Digitized Aug. 2016. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. Pp. 1. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:102663

- “The All-African Peoples Revolutionary Party and the Masses of African People Are Marching For: Pan Africanism.” Digitized Aug. 2016. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. Pp. 6. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:104939

- All-African People’s Revolutionary Party Southwest. YouTube: San Mateo California. Founded Apr. 1, 2020. Accessed Apr. 13, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/c/AllAfricanPeoplesRevolutionaryPartyNewMexico/featured

- “What is the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party (A-APRP)?.” All African People’s Revolutionary Party. Accessed Mar. 30, 2022. https://aaprp-intl.org/what-is-the-all-african-peoples-revolutionary-party-aaprp/

- Allman, Jean Marie. Quills of the Porcupine: Asante Nationalism in an Emergent Ghana. University of Wisconsin Publishing: Madison, WI. 1993. Pp. 191.

- “All African People’s Revolutionary Party Political Education Program.” Pp. 2.

- Muñoz Acebes, César. “Brazil Suffers Its Own Scourge of Police Brutality.” Americans Quarterly. AS/COA: New York, NY. June 3, 2020. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-suffers-its-own-scourge-of-police-brutality/

Image Credits

- “Photograph: Cleveland Sellers.” Cleveland L. Sellers Jr. Papers, 1934-2003. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Digitized Feb. 25, 2013. Accessed Mar. 30, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:23640

- “Home.” All African People’s Revolutionary Party. Accessed Mar. 30, 2022. https://aaprp-intl.org/

- “Kwame Nkrumah: The First President of the Independent Nation of Ghana.” Black History Heroes. 2020. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. https://www.blackhistoryheroes.com/2010/09/kwame-nkrumah.html

- Muñoz Acebes, César. “Brazil Suffers Its Own Scourge of Police Brutality.” Americans Quarterly. AS/COA: New York, NY. June 3, 2020. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. https://www.americasquarterly.org/article/brazil-suffers-its-own-scourge-of-police-brutality/