» Activist Education in Denver, CO by Mateo Mérida

In the 1960s, the United States saw some of the largest activist movements in the history of this country, with several movements being organized to underscore the structural failures uniquely impacting the country’s many ethnic communities. Arguably the most distinguished of all these movements was the Black Civil Rights Movement, which was so visible that it impacted the grassroots activism of other ethnic groups. One of these is the Chicane Movement, or El Movimiento, as it is often known in Spanish. Because of similar patterns in the history of Mexican, Hispano, Indigenous, and Chicane people (MHIC)1 in the Southwest, they drew direct inspiration from Black responses to systemic issues, particularly that of education. To understand how Black responses to substandard education influenced similar responses by Chicane2 activists in the Southwest, this blog post will tell the story of Escuela Tlatelolco, a chicanecentric activist school in Denver, Colorado, which would expand beyond the models preceding it.

Education was a primary objective of African American Civil Rights activists. Activists believed that receiving a high-quality education would provide the means for Black American people to attain upward mobility, and help to build up their communities, which was systematically withheld from them through substandard, Jim Crow apartheid education. For some scholars, the watershed moment that brought Civil Rights to the forefront of American consciousness was the decision of Brown v. Board of Education (1954). As schools resisted the integration required by the decision, the movement also became distinguished with Black families forcing the integration themselves by enrolling their own children into white schools3. Other responses saw Black activists creating their own institutions as a direct response to the failures of education provided to Black Americans at all stages.4

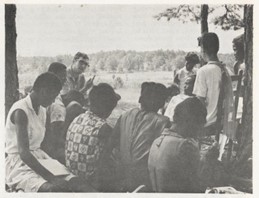

The most important of all of these responses, which had the most direct influence on MHIC people in Colorado was the Mississippi Freedom School. In 1964, members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) came together in Mississippi and created a series of summer camps throughout the state, filling in the gaps allotted to students in the segregationist education of the state. In these schools, they practiced reading and writing, taught African and African American history, and taught students how to stand up for their communities, as well as how to confront injustice in their daily lives5.

If education embodied the African American rejection of segregation, racism, and poverty, it held identical importance for MHIC communities in the Southwest. After the US seized the entire northern half of the territory of Mexico in 1848 (which accounts for all of current day Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, and Utah and the portions of Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming) the people remaining were illegally displaced of their lands and were coerced into continuing to labor on them for their new white landlords.6 Education served as a mechanism to reinforce this. Segregated schooling developed throughout the Southwest which relegated higher quality education for white Americans, and an education in manual labor for MHIC people.7

Shortly after the explosion of the Black Civil Rights Movement, cities like Los Angeles, Houston, and Denver became hotbeds of Chicane activism. The key organization of the Denver area was known as the Crusade for Justice. The Crusade interpreted that the American government was unable to address the needs of the country’s MHIC people, so they created their own institutions instead of waiting with no end in sight. Some of these include a newspaper addressing current events impacting MHIC people (El Gallo), a political party (La Raza Unida Party), and several community services.

Education was a primary focus of the Crusade for Justice. In March 1969, the Crusade organized a conference of Chicane student activists from across the Southwest to create a unified focus regarding how to address the needs of the MHIC people throughout the Southwest, which they called the nation of “Aztlán.”8 Education was one of the several points they discussed. “EDUCATION must be relative to our people, i.e., history, culture, bilingual education, contributions, etc. Community control of our schools, our teachers, our administrators, our counselors, and our programs.” 9 In this conference, the Crusade and those they invited agreed that the correct education for Chicane people was the education that they organized and created themselves.

The summer before, the Crusade had been busy practicing what they would preach, organizing what they called the “Freedom School.” The program was identical to the Freedom School in Mississippi, however, readjusted to Chicane people. The Colorado Freedom School taught Mexican history, tutored Spanish language, and taught traditional folk dances. Above all, however, it empowered students to stand up against injustice wherever they might encounter it.10

The Crusade’s Freedom School kick started what would become the first institutionalized response to substandard education for MHIC in Colorado. In March 1969, several students, who had participated in the Freedom School the summer prior, organized the West High Blowout, one of the largest school walkouts in the history of Denver Public Schools. Spanning across two days, 1500 students, parents, and community members marched in protest against the racism these students regularly encountered in the classroom, and the lack of representation they saw in their teachers and administrators, and in the curricula. The Crusade saw the West High Blowout as a moment of such importance, that it led to the creation of their own school the next Fall, which they called Escuela Tlatelolco.

The Crusade selected a name for their school that emphasized the cultural and nationalizing goals they envisioned for the school. Tlatelolco once was a district just outside the city of Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital city. After the fall of the Aztec Empire, Tlatelolco would also be the site of one of the first European-style education institutions in the Western hemisphere. It also was the site where scores of Mexican student activists were killed by the state for protesting the oppressive Mexican government. Taken all together, Escuela Tlatelolco told parents enrolling their children, that they would be taught to be proud of their Indigenous heritage, to attain educational excellence, and to give their lives to their communities in any way that they were able.

The Crusade for Justice would effectively cease to operate in the late 1980s, however, Escuela Tlatelolco continued to operate well into the 2010s. Unfortunately, it would be forced to close its doors because of gentrification and standardized testing. Denver witnessed unprecedented growth after the Housing Recession in 2007, when droves of people from other states flocked to underserved communities in Denver for its affordable housing. The booming prices directly impacted the accessibility of Escuela for the potential students who would otherwise have enrolled. As student enrollment struggled, poor performance in standardized testing reduced the funding available to Escuela, ultimately forcing it to close its doors in the summer of 2017. For forty-seven years, Escuela provided an education created by the Chicane community, for the Chicane community. Very few institutions of this kind continue to exist in the Denver area today, making Escuela a bittersweet memory in the Mexican American history of the Mile High City.

None of this would have ever taken place in this way without the direct inspiration of Black activists in the Southeast. Scholarship surrounding the Mississippi Freedom School has increased throughout the years, and it continues to be an inspiration today, as new Freedom Schools continue to arise to address shortcomings in education, and other pertinent social issues. But the deep influence of the Freedom School is not restricted to Black activism. SNCC activists in Mississippi proved to be so influential, that they created the first step in what would become one of the most successful responses to substandard education for Mexican American people anywhere in the Southwest.

If you are interested in more information concerning Escuela Tlatelolco, please feel free to visit the digital exhibition I created. Escuela of Aztlán was made to preserve Escuela in the historical memory of the general public, and as reference to a handful of videos, more images, and an annotated bibliography for further reading on the subject of Chicane education, El Movimiento, and Colorado history.

Sources

- “Chicane” describes an American person who is of Mexican/Hispano/Indigenous heritage, who participates in activist struggle to uplift Mexican people. This term was selected in order to unite the many tightly related and often conflated groups into one, single group to cohesively drive the Chicane Civil Rights Movement forward. “Hispano” describes a person of Spanish heritage living in the Southwest with ancestors in the region predating Mexican Independence. By consequence, Hispano people do not identify with Mexican heritage, but are regularly conflated as Mexicans. Some are also the descendants of Indigenous people, but do not identify as Indigenous people. “Mexican” specifically refers to people who have ancestry from the country of Mexico. This certainly means the millions of people who live in Mexico, but it also refers to people who have immigrated to other countries, as well as their children who retain Mexican heritage and culture. “Indigenous” describes the descendants of people who inhabited the Americas prior to violent colonization of Europeans, and who actively choose to identify with those original communities. Indigenousness does not necessarily supersede other cultural identities and extends beyond modern-day borders. See first image as a comprehensive aid.

- Spanish language prioritizes masculinity when describing groups. The letter “o” at the end of a group-term describes a group of people as masculine (even if only one single masculine person is present), while the “a” suffix describes a group as feminine. To break from the masculine-normative tendency of Spanish language while accommodating gendered neutrality, I propose the use of “e” to accommodate both binary and non-binary Chicane people.

- C. Mateo Mérida-Sparling, “Archive Spotlight: Somebody Had to Do It by Mateo Mérida,” Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, Mar. 11, 2022, accessed Apr. 12, 2023, https://avery.cofc.edu/somebody-had-to-do-it-by-mateo-merida/.

- C. Mateo Mérida-Sparling, “Part 3: Lowcountry Resistance,” Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, Feb. 17, 2023, accessed Apr. 12, 2023, https://avery.cofc.edu/part-3-lowcountry-resistance-by-mateo-merida/; C. Mateo Mérida-Sparling, “Archive Spotlight: Malcolm X Liberation University,” Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, Mar. 11, 2022, accessed Apr. 12, 2023, https://avery.cofc.edu/archive-spotlight-malcolm-x-liberation-university-by-mateo-merida/.

- Howard Zinn, “Schools in Context: The Mississippi Idea,” (Atlanta, GA: Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), Avery Research Center: Myrtle Glascoe (unprocessed), box 1.

- Reies López Tijerina, They Called Me “King Tiger”: My Struggle for the Land and Our Rights (Houston, TX: Arte Público Press, 2000)

- The discourse between education as a tool to oppress and as a tool to uplift is not in any way restricted to Chicane activists. One of the most notable of these intellectual debates in Black American history is that between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois. While Washington argued that stigma should be removed from the manual labor forced upon the Black community, DuBois argued that providing education to the most talented of the Black students would create an upward community for Black Americans overall. Similar discussions of the role of education as a tool of oppression are also palpable in US-Indigenous history, where boarding schools were used as tools of cultural erasure and genocide.

- Legend tells that the Mexica people, often called the Aztecs, migrated from some place in the north to Lake Texcoco, where Mexico City is today. This mystical land that they left behind was called “Aztlán.”

- “The Program Of El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán,” El Gallo, Apr. 1, 1969, 10. Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection.

- Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, Message to Aztlán: Selected Writings of Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, (Houston, TX: Arte Público Press, 2009), 172-5.

Image Credit

- Venn diagram of Chicane/Hispano/Mexican/Indigenous terminology; see first citation for more information. Self-made.

- Image of students and teachers in the Mississippi Freedom School from Howard Zinn, “Schools in Context: The Mississippi Idea.” 1964. Myrtle Glascoe papers (unprocessed), courtesy of the Avery Research Center.

- Image of students and teachers in front of Rivera School. Near Trinidad, CO. c. 1890s. Denver Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed Apr. 4, 2023. https://digital.denverlibrary.org/digital/collection/p15330coll14/id/602

- Image of protesters from the West High Blowout. Denver, CO. March, 1969. Colorado Public Radio. Accessed Feb. 18, 2023.

- Image of front of Escuela Tlatelolco. c. 2015. Latino Cultural Arts Center. Accessed Mar. 15, 2023.

Author

Mateo Mérida is a Public History master’s candidate at the College of Charleston, a graduate assistant at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, a certified interpretive Guide and recipient of the Karen Chambers Fellowship.