» A Life Well Lived Lucille Whipper 1928–2021

During her lifetime, Lucille Simmons Whipper acquired numerous achievements and garnered countless accolades. But one of her most shining accomplishments is facilitating the establishment of her former school, the Avery Institute, into the College of Charleston’s Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. Her initiative and perseverance steered the transformation of Avery into an archival repository, small museum, and cultural center for academic and public programming.

Beginning the Legacy

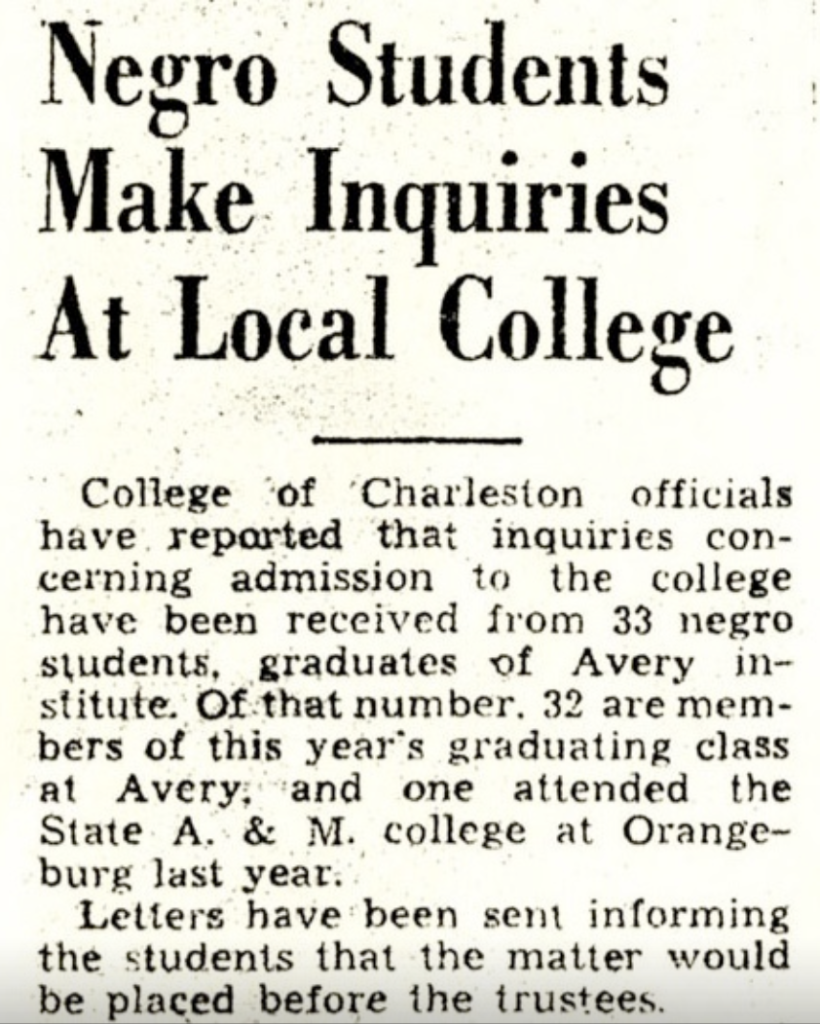

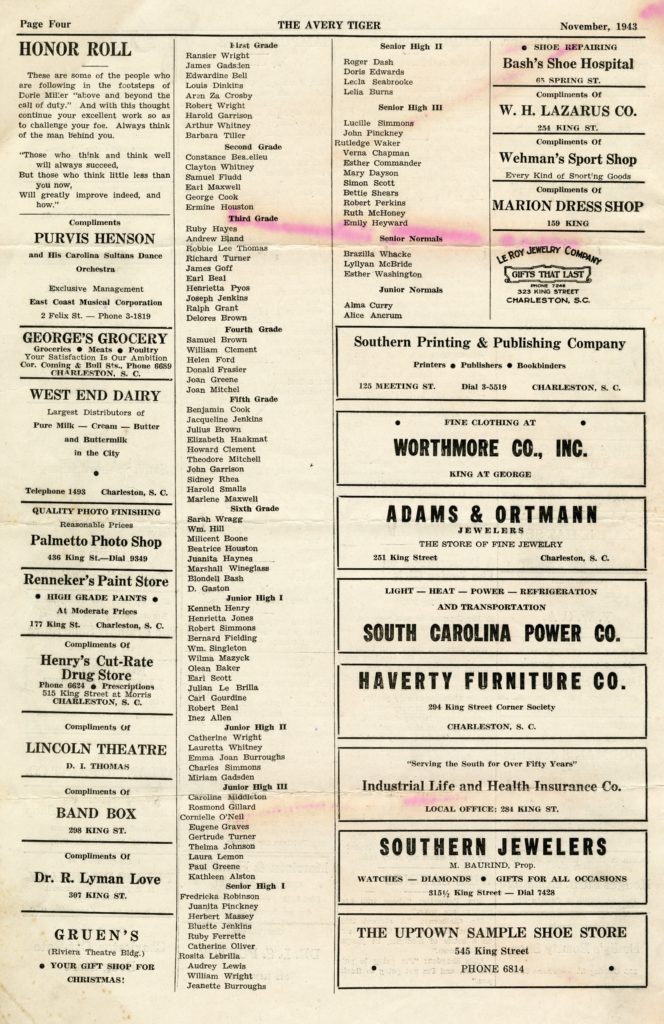

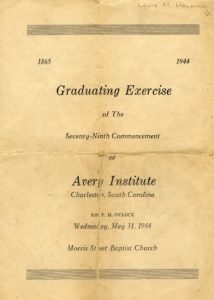

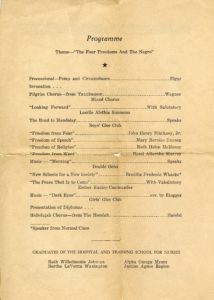

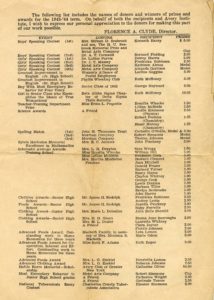

There are not many people who can be connected to one institution for nine decades. In the 1930s and 1940s, Whipper, then Lucille Simmons, walked the halls of the Avery Institute, soaking in the knowledge of premier educators who advocated for civil rights and a just society. She was admired by her peers and was an honor roll student throughout her tenure. Her graduating class, 1944, was pivotal in shifting the dynamic of Charleston and South Carolina when they applied to College of Charleston, knowing they would likely be denied due to their race. In an act of defiance, the College would modify its entire governance structure to maintain white supremacy. The Avery Institute instilled challenging the status quo in its students, and Mrs. Whipper was among that fold.

Saving the Legacy

Following the Avery Institute’s closure in 1954, the structure built for and by African Americans’ upward mobility was turned over to the Palmer Secretarial College, currently Trident Technical College. Many Averyites note how the building was condemned for being uninhabitable, but no nail was struck for them to move in. Today, we recognize this process of gentrification and are equipped to fight the forces; however, during a time of de jure injustice, it took brave activists and organizers to mount campaigns to save our spaces.

Destined to become condominiums in the late 1970s when Palmer College’s vacating the space, Dr. Margaretta P. Childs, a former archivist at the City of Charleston, implored Whipper to help do something to save the Avery buildings. At first, Whipper, then the head of human relations at the College of Charleston, was hesitant as she was active in her denominational work, numerous organizations, boards, and committees. Yet upon further consideration, knowing how important Avery Institute was and envisioning what a new Avery could be, she set out to rally the troops to save the building. Initially, Whipper notified her members of the Charleston Chapter of the LINKS, Incorporated, a national service organization of African American women volunteers who aim to solve community problems. From this meeting, they organized a campaign to include graduates of Avery Institute (Averyites), College of Charleston administrators and faculty, leaders of civic institutions, and community activists to form the Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture (AIAAH&C). Of note, Whipper advised the membership that the AIAAH&C must represent “the total Black experience in the Lowcountry.”

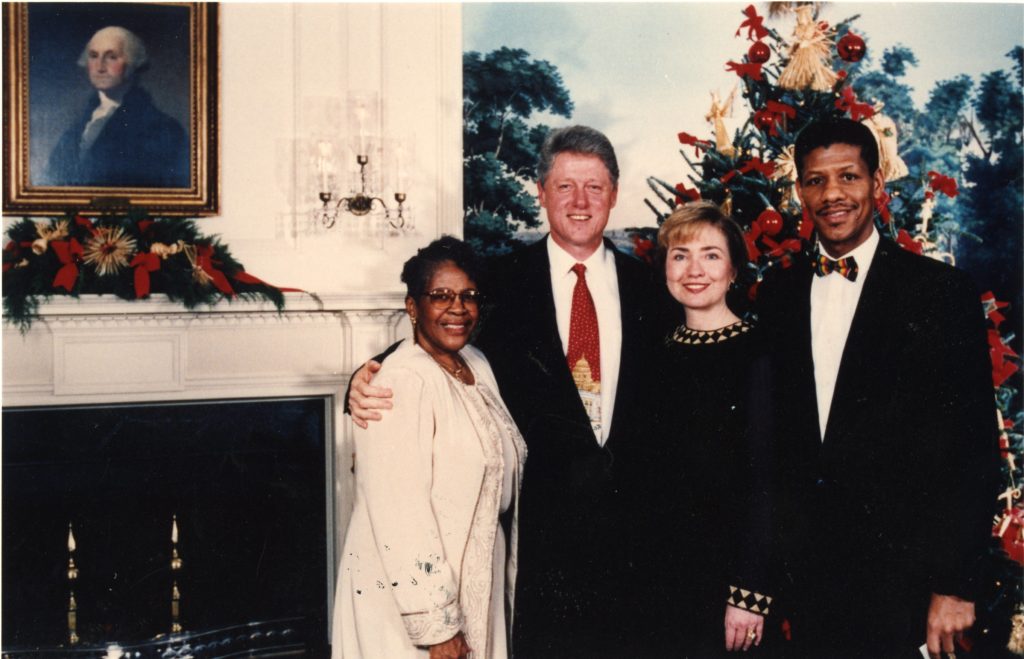

As founding AIAAH&C president (1978–1984, 1995–1990), Whipper worked with the Charleston Museum, Gibbes Museum of Art, and various cultural institutions to increase the presentation of programs highlighting African American contributions in history and culture. She also organized and served as director of two historic projects: South Carolina Voices of the Civil Rights Movement and Esau Jenkins-A Retrospective View of the Man.

Through collaborative lobbying efforts, and with assistance from the Office of Governor Richard Riley and the Charleston Legislative Delegation, AIAAH&C successfully achieved its goal in establishing the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture as a state-supported institution under the auspices of the College of Charleston, the same institution that denied her admission forty years prior.

Reflection from Aaisha Haykal, Manager of Archival Services

I initially met Mrs. Whipper when I was a fellow at the College of Charleston’s Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture in 2011. She was one of the first native Charlestonians I met. Meeting with her helped me gain more realization about the Avery Research Center’s importance not just for the scholars and patrons who come from afar to do research, but also for the local people of Charleston and the South Carolina Lowcountry. The Avery Research Center is not just a collection of images and documents; it is also a space about the people, a definitive statement that says, “We were there. We did the work. We will continue to do the work. We are not going anywhere.”

Additionally, she placed the Avery Research Center in the larger conversation of Black museums and archives and how they are vital for education and challenging the status quo. Mrs. Whipper took an active role in making the Avery Research Center visible on the College of Charleston campus and in the greater Charleston community. She worked closely with the Avery Research Center’s first executive director, the late Dr. Myrtle Glascoe, to promote the Avery Research Center and to obtain collections from communities in the Sea Islands, Averyites, and members of the Black Charleston community. These collections are still some of the most requested items from researchers.

Mrs. Whipper laid a path for the Avery Research Center team to follow as we sustain and push forward with the legacy of telling the stories of Black life and history in the South Carolina Lowcountry and beyond.

Aaisha Haykal, Avery Research Center

Continuing the Legacy

After her directorship tenure with the Avery Institute board, Mrs. Whipper remained an ardent advocate for her beloved Avery. If the building or administration needed something to function properly, Whipper was there on the frontline inquiring and insisting on results. Known for her communication skills, when Whipper spoke, people listened and responded.

If not for Mrs. Whipper, and the enduring efforts of the Avery Institute of Afro-American History and Culture board, we would not be here to preserve, document, and exhibit the rich history of Charleston, the South Carolina Lowcountry, and the world, including her expansive collection of 188 boxes featuring her life’s work. Nor would we be here to expand initiatives of social justice and change, which Whipper passionately fought for throughout her life. Without Lucille Simmons Whipper’s leadership, tenacity, and vision, the Avery Research Center would not be the stellar and renowned research institution it currently is. We are eternally grateful for her dedicated stewardship.