» Imperialism, Decolonization, and Kwame Nkrumah by Mateo Mérida

Although the Civil Rights Movement is completely inseparable from Black history in the United States, the American Civil Rights Movement is only one element of global Black history in the 20th Century. While several millions of people were impacted by Civil Rights policies in the United States in the mid-1960s, across the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, hundreds of millions of Black people were being impacted by the movement of European decolonization. Before the whole of the African continent would take back its own independence, Ghana—under the leadership of Kwame Nkrumah—was a leader in the decolonization movement and early independence period.

In the 19th Century, while colonies across North and South America began to declare themselves as independent states, Europe was undergoing what has come to be called the Industrial Revolution. This was a historical era distinguished by the widespread, and first time uses of machines to expedite the processes that previously required manual labor. With expedited labor, this also meant that goods could be manufactured at a much higher volume, which created a massive surplus, which could then be sold at a profit, creating the economic mode of production called Capitalism. This new use of machines however, did not come without a substantial cost. While many of these machines require coal, other machines required massive volumes of lumber, cotton, and many other raw materials which fueled this revolution in production, and endless pursuit of profit.

Imperialism—the process in which a polity or state coerces and maintains power and hegemonic authority beyond the confines of one’s own polity or state, often through means of military, social and economic violence—stole these raw materials to fuel the Industrial Revolution. Since industrialization was contemporaneous with movements of independence across the Americas, Europe began to turn their attention to Africa and Asia to address their industrial needs.

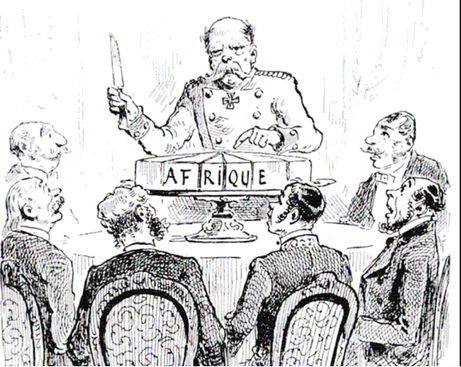

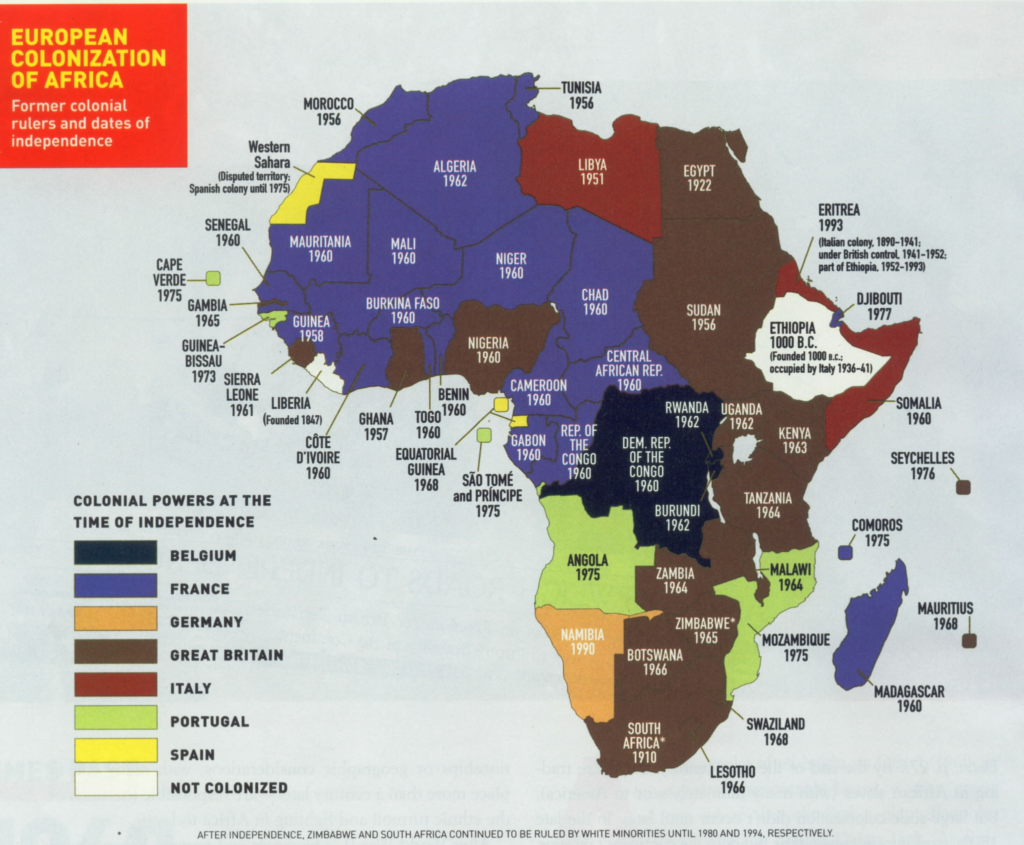

With some of the first Portuguese colonies in Africa appearing in the late 16th Century in Angola, followed by the French conquest of Senegal, and the Dutch colonization of the South African Cape, little by little, Africa began to fall deeply under the control of European imperialists. This escalated with the Berlin Conference in 1884, where European heads of state (in the absence of any African people or representatives) delegated borders in order to codify who controlled which part of Africa and more importantly its resources. By 1914, all of Africa, except Liberia and Ethiopia fell under the control of European Imperialism.

One of many of these colonies was the Gold Coast in Western Africa, or Ghana as it is called today. Ghana was used to produce cocoa and rubber in high volumes, with most profits going to the land-owning British capitalists. As British industries exploited African land, religion was a tool for colonizing African minds. Missionaries established many schools in Ghana, to facilitate the process of Westernizing African people. What they likely had not realized however, was that these schools would provide educational foundation for one of the most important de-colonizing figures in world history.

Kwame Nkrumah was born in Nkroful, Gold Coast, received a Catholic education, and dreamed of being a priest when he grew up. As he grew however, he decided to further his education, and attended Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. He pursued two master’s degrees in philosophy and education at University of Pennsylvania, and then later went to study in London, but never completed his degree. In his studies abroad, Nkrumah read Karl Marx, Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. DuBois, and became highly aware of the oppression of African and African descended people around the world. He also was a member of the 5th Pan-African Congress, who believed that the only solution to racism globally and colonialism in Africa was to supplant it with a unifying Socialist state in Africa.

While Nkrumah was studying in Europe, pressure for European decolonization began to build with the onset of WW2. As the continent found itself at war with fascism. Ally powers decried the racism, imperialism and oppression of Nazi Germany, while sending in soldiers from African and Asian colonies to defeat Japanese, Italian and German fascists in the field. Yet, once the war was over, these soldiers then went home to a colony where they were treated as second class citizens. As a direct result of widespread protest, media coverage, and financial disincentive to continue to maintain the political project, India gained its independence, and established itself as a republic in 1950.

As the world was focused on the developments in India, Kwame Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in 1947, where he became the face of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), which sought to establish a self-governing Gold Coast immediately. Nkrumah broke away from the party two years later, founding the Convention People’s Party (CPP), which also sought to free the Gold Coast from British imperialism, but with the aspiration of establishing a socialist state.

Nkrumah became highly popular with the people of the Gold Coast, which carried over into his establishment of the CPP. As the movement for the colony’s independence began to come into view, Nkrumah was appointed the first prime minister of the Gold Coast. In the general election of general on July 17, 1956, the CPP won more than half of all of the seats of the Legislative Assembly, and quickly followed this success with an assembly vote on August 3rd to change the Gold Coast’s name to Ghana, and to make it an independent country. The vote was successful, and Ghana was to become a free country in March of the following year. Nkrumah, as the head of the CPP and the prime minister of the Gold Coast continued his position as the prime minister of Ghana, ultimately becoming the president of Ghana in July of 1960.

The Pan-African Socialist became an icon of African independence around the globe, as Ghana became the first ex-colony of Great Britain in Africa to win its independence and bring decolonization to Africa. Nkrumah quickly went to work, building a hydroelectric dam, and founding the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. As a Pan-African leader of the movement to end African colonization, Nkrumah also deployed troops in Congo to support Congolese people in the onset of the Congo Crisis.1

As popular as Nkrumah was as prime minister, as president, his popularity steadily decreased to an ambivalent end. Within his fourth year of presidency, Nkrumah and the CPP passed legislation which made the CPP the only lawful political party, while also naming Nkrumah the permanent president, not just of the CPP, but of Ghana. Nkrumah had become a bona fide dictator. In his Pan-African view of the continent, and consequently of Ghana, Nkrumah also struggled substantially with tribalist self-determination, as he found himself nearly approaching a civil war with the Asante people indigenous to Ghana, who felt Nkrumah’s administration failed to address the needs of Asante people. Coupled with rising unemployment and inflation, Nkrumah became profoundly unpopular among Ghanaian people in every corner of the country.

Nkrumah was deposed from office in 1966, and spent the rest of his life in Guinea. It is safe to say that Nkrumah’s welcome to Guinea was a warm one, as he was given the honorary title of co-president of Guinea, sharing it with the presiding president Ahmed Sékou Touré. There, Nkrumah also joined forces with Kwame Ture, who was formerly a prominent member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Two years after his deposition, Nkrumah founded the All African People’s Revolutionary Party (AAPRP), which inherited Nkrumah’s socio-political philosophy, and sought to export it globally. Nkrumah would live the rest of his life in Guinea until his passing in 1972.2

Kwame Nkrumah today carries a legacy that celebrates him as a leader and symbol of anticolonialism, Pan-African Nationalism, and a champion of Ghanaian independence. For others, Nkrumah leaves a legacy of a squandered economy, anti-democracy, and is seen as a justification for anti-Socialism. Still, it seems that his legacy of African self-determination lingers the furthest today. As a person who survived five separate assassination attempts, before he ultimately passed away, the saying persists: Nkrumah never dies.

Footnote

- This is not to ignore other states in which Africa had maintained their independence all the way through the colonial era (Ethiopia), or were relinquished significantly earlier by imperialists than the much broader European decolonial movement (notably Liberia) Egypt was granted independence from the British Empire in the 1920s, but would remain the only colony to be released by Great Britain in Africa until Ghana in 1957. Tunisia and Morocco were both cut free of the French Empire immediately before.

- Ture was formerly known as Stokely Carmichael.

Bibliographic References

- Adejumobi, Saheed. “The Pan-African Congresses, 1900-1945.” BlackPast.org. July 30, 2008. Accessed Apr. 8 2022. https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/pan-african-congresses-1900-1945/

- “Ahmed Sékou Touré.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia: United States. Feb. 20, 2022. Accessed Apr. 13, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ahmed_S%C3%A9kou_Tour%C3%A9

- “The All-African Peoples Revolutionary Party and the Masses of African People Are Marching For: Pan Africanism.” Cleveland L. Sellers, Jr. Papers 1934-2003. Digitized Aug. 2016. Accessed Mar. 31, 2022. Pp. 1. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:104939.

- Allman, Marie Jean. Quills of the Porcupine: Asante Nationalism in an Emergent Ghana. The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI. 1993.

- Austin, Gareth. “Labour and land in Ghana, 1874-1939: a shifting ratio and an institutional revolution.” Australian economic history review. Vol 47, no. 1. pp 95-120. https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/4392/1/Labour_and_land_in_Ghana_%28LSERO_version%29.pdf

- CGTN Africa. “Faces Of Africa- Kwame Nkrumah.” CGTN Africa. YouTube: San Mateo, CA. Dec. 9, 2014. Accessed Apr. 8, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMY0iTcspNA

- “Kwame Nkrumah.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia: United States. March 22, 2022. Accessed Apr. 8, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwame_Nkrumah

- Young, Crawford. The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective. Yale University Press: New Haven, CT. 1994.

Image Credits

- Banks. “Scramble for Africa: Cartoons.” Mr. Banks’ AP World History Page. Feb. 17, 2016. Accessed Apr. 8, 2022. https://mrbanksapworldhistory.weebly.com/2015-newsfeed/scramble-for-africa-cartoons

- https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/nkrumah

- Strohm, Rachel. “African colonization & independence.” Rachel Strohm: Nairobi, Kenya. Feb. 1, 2014. Accessed Apr. 8 2022. https://rachelstrohm.com/2014/02/01/african-colonization-independence/

- Zuanzuanfuwa. “The porcupine on the National Emblem of the Kingdom of Ashanti.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia: USA. Mar. 20, 2022. Accessed Apr. 8 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asante_Kotoko_S.C.#/media/File:Ashanti_Empire_Emblem.svg

- “Kwame Nkrumah.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia: United States. March 22, 2022. Accessed Apr. 8, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwame_Nkrumah