» History News: Charleston Cigars and the Great Resignation by Mateo Mérida

In the two years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the largest effects since then has been what is coming to be known as “The Great Resignation.” As more and more white- and blue-collar laborers In the two years since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the largest effects since then has been what is coming to be known as “The Great Resignation,” in which increasing numbers of white- and blue-collar laborers across the United States consistently submit two weeks notices, in pursuit of better work. It should not be lost in context that this is the most visible facet of a much larger worker’s movement sweeping the United States. From Nabisco, to Kellogg’s, John Deere, Amazon and Starbucks workers across America are striking, protesting, and boycotting for a better work environment and benefits. This, is a continuation of a long protracted struggle for liberation in the United States, and the South Carolina Lowcountry.

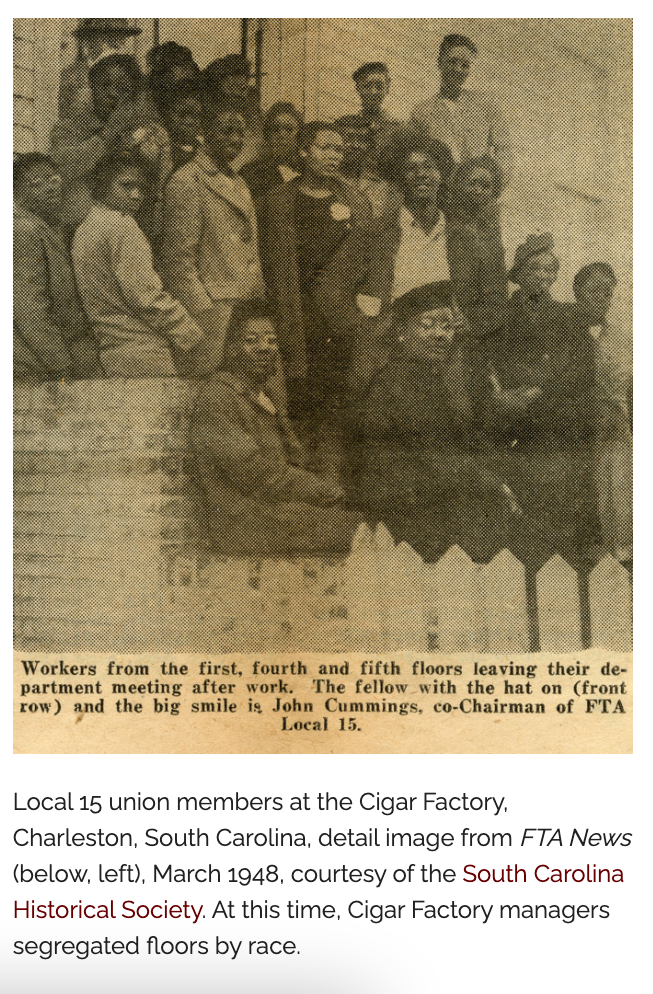

Sitting on the intersections of East Bay and Columbus street, one of the most visible buildings in the upper Charleston peninsula once operated an American Tobacco Company (ATC) factory, established in 1903. Prior to World War II (WWII), women were the majority of the factory’s labor force. With the war’s onset however, as men traveled to fight across the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, Black and white women became the primary earners for their families. Pay for the workers of the Charleston Cigar Factory (a subsidiary of ATC) prior to WWII was abysmal, as they employed 1400 workers, and paid out almost of $1 million in payroll, which is equivalent to less than $12,135 a year per employee when adjusting for inflation since 1930.1

The meager pay earned by employees was in no way compensated by the quality of their place of work. Virginia Bonnette was an employee of the Cigar Factory in 1939 and described what it was like to work there in her oral history with the Citadel’s Dr. Kerry Taylor. Bonnette described that the factory negatively impacted her health, to the point that she would vomit so regularly her doctor incorrectly diagnosed her as pregnant. Further, upon employment, she was required to purchase two uniforms which were to be worn as she worked. While she remembers it being difficult to constantly keep them clean—especially since they were all white uniforms—she risked being sent home if the uniform was even slightly unkempt. Bonnette only worked there for a few short months, but many employees, far older than she was at 17 had been working there for many years. Much like how COVID-19 today would create change in today’s labor force, the end of WWII brought change to the factory.2

At the end of the war, the factory received government subsidies, which were absorbed by property owners and managers, and were never distributed to the workers. Stagnant wages, mismanaged funds, then connected with regular segregation and discrimination within the factory walls ultimately boiled over into a strike in October of 1945 (and other ATC factories in Trenton, NJ and Philadelphia).3

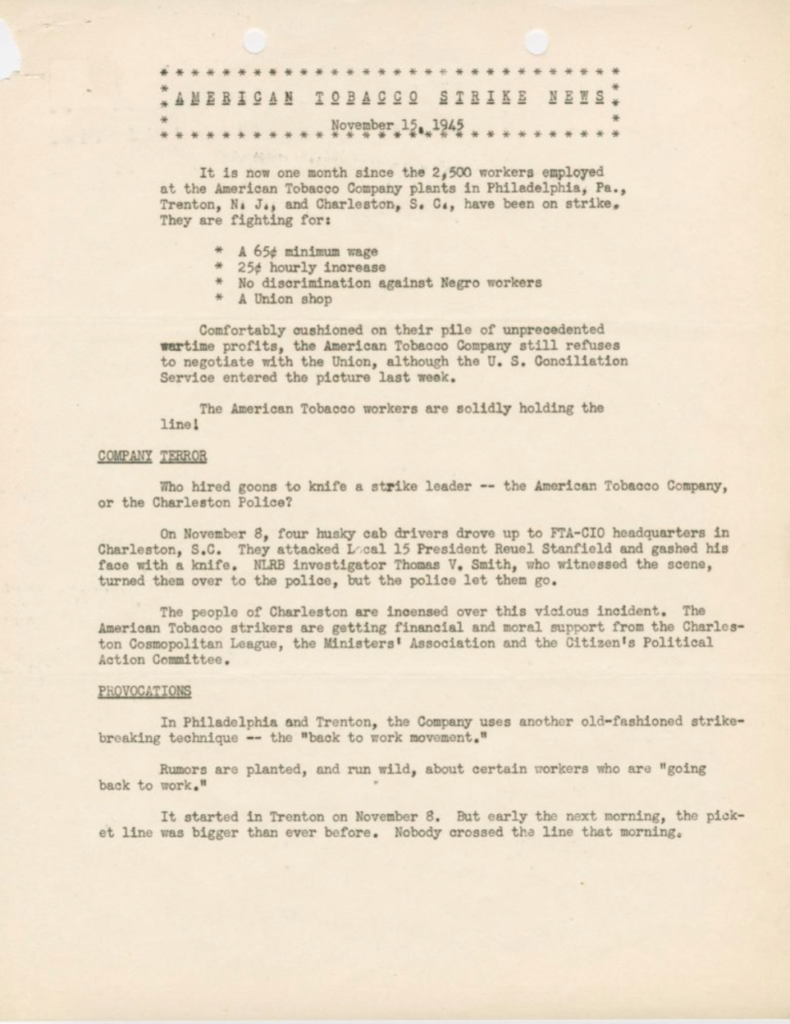

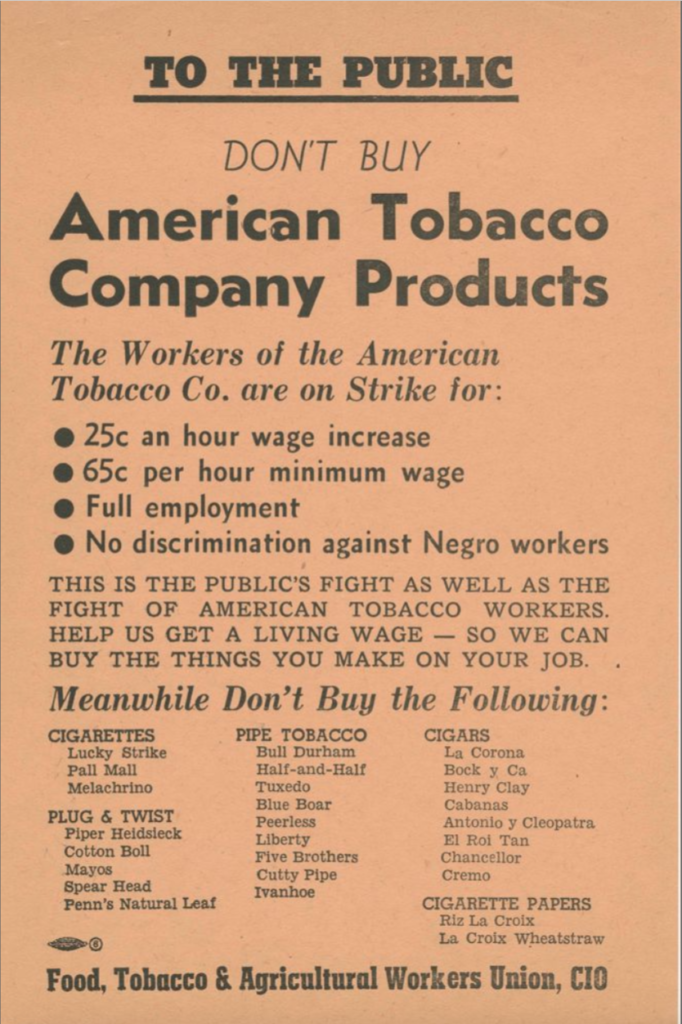

For a strike to be successful, it needs to garner widespread popular support. In The American Tobacco Strike News, a publication created by employees participating in the strike, several attempts are made to garner such support. At the very top of the page, it documents the strike demands. On the second page, it also makes a point to demonstrate the engagement of politicians in the strike, as well as the broader support it already has from various unions. In the final sentences however, it makes it perfectly clear why any potential reader should be invested in the strike. It writes “Victory in this strike will be a blow to sub-standard wage industries. It will cut across North-South wage differentials. It will lay a cornerstone for fair employment practices in industry. It’s a crucial fight. It’s your fight too.” The reason that such popular support became so important for the strikers is a direct result of how they engaged the public, which came in the way of a boycott. While the factory struggled to sustain its own productivity and profits with its workers striking, the strikers applied much more pressure in reducing profits so the wider population refused to buy American Tobacco Company products.4

The strike coupled with the boycott ultimately forced the ATC to cooperate with the strikers’ demands in March of 1946. With the strike’s end, the factory workers received a pay increase, and a lessening of racialized discrimination within the factory itself. However, the strikers did not gain everything that they wanted. The wage increase grew by $0.08 instead of the $0.25 which they requested. While the strikers were successful in lifting some of the racial restrictions on certain jobs within the factory, white workers often encountered preferential treatment for upper level positions. Still, while these gains were incomplete, the Charleston Cigar Factory Strike of 1945-1946 showcased the power that workers had within their place of work.5

In 2021, the pandemic empowered the workers of the Kellogg Company to strike for better wages, a guarantee not to close down a handful of plants which would have rendered many workers unemployed, and the banishment of a two-tier pay system. Just like the Cigar Factory Strike, much of their success was highly contingent upon popular support, as a boycott of Kellogg’s products coupled with their strike successfully raised their wages which will match inflation, placed a moratorium on the closing plants, while also retaining their jobs, despite the hiring of “permanent” replacement employees, all while making no concessions for Kellogg’s in their negotiation.6

Seventy-six years later, as the current Great Resignation has continued to grow, writers have considered a handful of ideas as to what has caused this wave of change in the workplace. One publication argues it’s a result of toxic culture, which they describe “include[s] failure to promote diversity, equity, and inclusion; workers feeling disrespected; and unethical behavior”.7

Other scholars have recognized that the very economy itself drives the continuation of the Great Resignation. As inflation has increased, wages have stagnated, so workers have searched for better pay elsewhere, and have been generally successful in finding it.8

As is reflected in the examination of the Cigar Factory Strike, these are not new problems faced by the working class. In a letter written by Harold J. Lane, the Secretary-Treasurer of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers Union of America, he described American Tobacco’s effort to bring workers back into the factory as the “back-to-work movement.” Similar language is being used today in the effort to end virtual and flexible work schedules in exchange for returning to in-person work back to office buildings.9

While the strikers may not have had all their demands met, their conditions were measurably improved from before their strike. Labor strikes in the 1930’s created the 40-hour work week, the weekend, and the minimum wage. In 2022, this new wave of labor movements and the Great Resignation could mean the difference between working virtually or in an office, earning a living wage, and ending “toxic” work culture.

Sources

- “Historical Background of Cigar Factory.” Charleston’s Cigar Factory Strike, 1945-1946. Lowcountry Digital History Initiative: Charleston, SC. May, 2014. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/cigar_factory/historic_background_cigar_fact

- Bonnette, Virginia. “Virginia Bonnette, Interview by Kerry Taylor and Virginia Ellison, March 15, 2012.” The Charleston Oral History Program. The Citadel Archives & Museum: Charleston, SC. Mar. 15 2012. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. Pp. 13-18. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:63995

- “Escalating Tensions Before the Strike.” Charleston’s Cigar Factory Strike, 1945-1946. Lowcountry Digital History Initiative: Charleston, SC. May, 2014. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/cigar_factory/escalating_tensions_before_the

- Lane, Harold J. “American Tobacco Strike News.” Isaiah Bennett Papers, ca. 1932-2002. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Nov. 15, 1945, Accessed Mar. 24 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:32930.

- “The Strike Ends.” Charleston’s Cigar Factory Strike, 1945-1946. Lowcountry Digital History Initiative: Charleston, SC. May, 2014. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/cigar_factory/the_strike_ends.

- Woodward, Alex. “Kellog’s union workers end 11-week strike after approving new contract.” The Independent: London, UK. Dec. 21, 2021. Accessed Mar. 24, 2021 https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/kelloggs-strike-union-contract-vote-b1980259.html

- Sull Donald, Charles Sull, Ben Zweig. “Toxic Culture is Driving the Great Resignation.” ACMP Nor Cal. Jan. 26, 2022. Accessed Mar. 15, 2022. https://www.acmpnorcalchapter.org/changemanagement-articles

- Ibid.

- Lane, Harold J. “Letter to regional Union administrators from Harold J. Lane, Secretary-Treasurer of Food, Tobacco, Agriculture and Allied Workers Union of America, CIO.” Isaiah Bennett Papers, ca. 1932-2002. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Nov. 30, 1945. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:32903

Image Credits

- Cebulka, Andrew. “Cigar Factory – Charleston.” Cigar Factory. Charleston, SC. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://cigarfactorycharleston.com/

- “Historical Background of Cigar Factory.” Charleston’s Cigar Factory Strike, 1945-1946. Lowcountry Digital History Initiative: Charleston, SC. May, 2014. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/cigar_factory/historic_background_cigar_fact

- Lane, Harold J. “American Tobacco Strike News.” Isaiah Bennett Papers, ca. 1932-2002. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. Nov. 15, 1945, Accessed Mar. 24 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:32930

- “Publicity flyer asking the public to boycott American Tobacco Company products.” Isaiah Bennett Papers, ca. 1932-2002. Avery Research Center at the College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. 1945. Accessed Mar. 24, 2022. https://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:32902