» History News: COVID-19’s Impact on Charleston’s Black Community by Mateo Mérida

While there is no corner of the world today that has remained completely untouched by the COVID-19 pandemic, certain places have felt the impact more severely than others. Structural racism has created a feedback loop of poverty, ecological degradation and lack of resources in Black neighborhoods, which has led to an abundance of poor physical health for Black Charlestonians. As such, COVID-19 has disproportionately devastated the Black community, infecting several thousands of African American families across the Charleston area.1

One of the largest factors that primed COVID-19 to have such a negative impact for Black Charlestonians is the role which they play in the region’s labor force. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) defined an essential worker as “as those who conduct a range of operations and services in industries that are essential to ensure the continuity of critical functions in the United States.” In 2015, more than 70% of Black Charlestonians fit this description, as most are employed in shipping and warehousing, accommodation and food service, and retail. More than one quarter of Black women alone worked in health care services. While everyone else was required to quarantine, Black people were overwhelmingly among the first to be exposed to the virus in the Charleston area. By working in industries that did not afford them the option to lockdown or work from home, their likelihood of exposure to the virus increased significantly.2

Along that same line, the labor of Black people made a lockdown possible for the rest of the community, as they worked checkout lines in grocery stores across the county and shipped masks and Lysol from warehouses, while also nursing those who were battling the virus themselves. Even with a national lockdown, many Black families in the Charleston area were stuck managing the pandemic, so that the rest of the county and region could stop the spread of the virus.

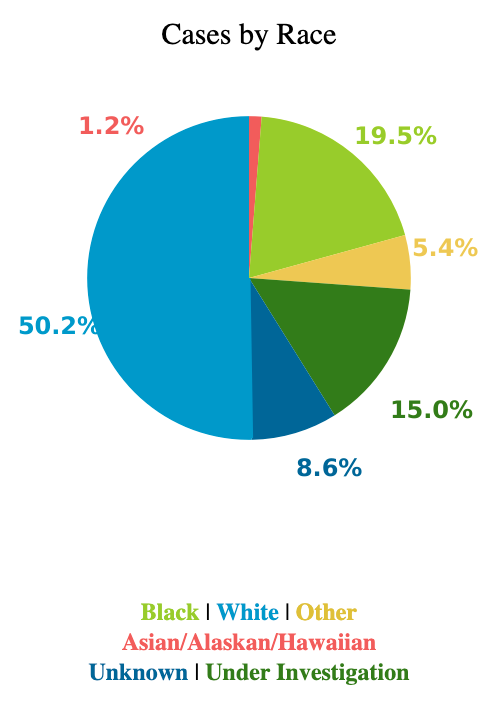

The toll all of this took is evident when analyzing the number of COVID tests in Charleston County. While Black people accounted for nearly a quarter of the Charleston County’s population in 2020, less than 20% of tests taken were by Black people. Hours of operation for testing sites tends to coincide with business hours, during which time most essential workers would most likely be on the job. Further, given the low rate of pay most receive, taking off work to get tested was not a practical option. Although this increases the risk of spreading the disease to others, the alternative is risk of starvation, utilities being cut off, houselessness, etc.3

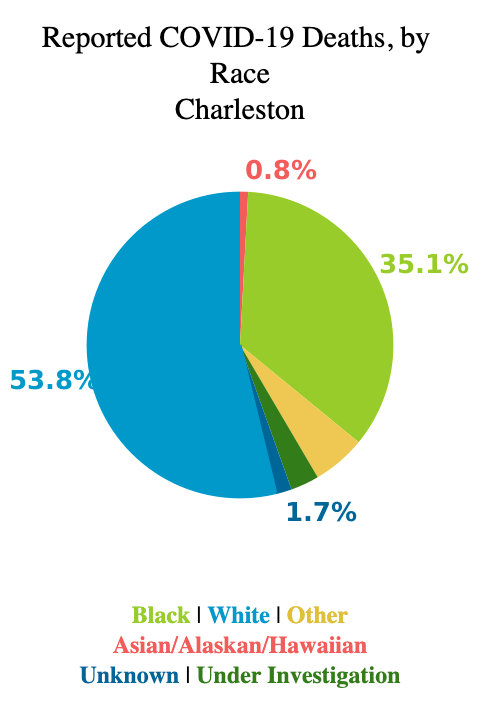

Where Black Charlestonians literally could not afford to be sick, the trap set by “essential” labor cost the lives of several hundreds of Black Charlestonians. Of all COVID-19 deaths in Charleston County, well over a third of those were Black, despite only being one quarter of the population.4

The sheer devastation of the pandemic on Black Charleston did not happen in a vacuum. It is the direct result of several compounding factors, such as the environmental quality of Black neighborhoods or lack thereof, poverty, depressed wages, and the stagnancy of upward mobility of Black Charlestonians since the Jim Crow era. Structural racism put Black Charlestonians in a constant fight to survive before the pandemic, which became yet another fatal element added to the mix. Black Charlestonians have a high prevalence of lung diseases such as Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease and Lung Cancer, which largely can be explained by the environmental pollution found in many Black neighborhoods in Charleston. COVID-19 can violently attack the lungs of those infected. For people who already have medical histories with lung disease, defeating COVID-19 becomes abundantly more difficult.5

The death rates immediately become even more severe with the compounding factors of poverty. If the primary earner in a Black family cannot afford to take a day off work or quarantine when exposed to the virus then this person exposes more people to the virus, and takes longer to fight it off as they are not resting at home. Furthermore, people in poverty often cannot afford to pay for medical services, and are abundantly more likely to have insurance plans with meager coverage if they have insurance at all. In the event a Black person infected with COVID-19 is forced to seek medical attention due to the severity of symptoms, they would be lucky to find a hospital bed to accommodate them considering how overwhelmed local medical facilities have been at different points throughout the pandemic. COVID-19 will hold a lasting memory for all people worldwide who have lived through it. As of early February 2022, COVID-19 has accounted for over 912,000 deaths across the United States. Still, what this number does not reflect is the way in which the social structures created within the United States set the stage to impact certain ethnic groups and communities significantly harder than it has others. Charleston’s Black community was set up for failure long before COVID-19, and the onset of the pandemic merely added insult to injury.6

Sources

- Mérida-Sparling, C. Mateo. “Health in the Disparities Report.” Avery Research Center: Blog. Avery Research Center, Charleston, SC. Feb. 11, 2022. Accessed Feb. 16, 2022. https://avery.cofc.edu/history-news-health-in-the-disparities-report-by-mateo-merida/.

- Avery Research Center. “The State of Racial Disparities in Charleston County, South Carolina, 2000-2015,” College of Charleston: Charleston, SC. 2017. pp. 27; CDC. “Interim List of Categories of Essential Workers Mapped to Standardized Industry Codes and Titles.” Vaccines and Immunizations. Center for Disease Control: Atlanta, GA. March 29, 2021. Accessed Feb. 2, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/categories-essential-workers.html#:~:text=This%20interim%20list%20identifies%20%E2%80%9Cessential,the%20United%20States%20(U.S.)

- DHEC. “South Carolina County-Level Data for COVID-19.” South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control: Columbia, SC. Feb. 6, 2022. Accessed Feb. 9, 2022. https://scdhec.gov/covid19/covid-19-data/south-carolina-county-level-data-covid-19.

- DHEC. “South Carolina County-Level Data for COVID-19.” South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control: Columbia, SC. Feb. 6, 2022. Accessed Feb. 9, 2022. https://scdhec.gov/covid19/covid-19-data/south-carolina-county-level-data-covid-19. See “Deaths” tab.

- The State of Racial Disparities, 62-66.

- Our World in Data. “COVID-19 Data Explorer.” Our World in Data. University of Oxford: Oxford, England. Feb. 9, 2022. Accessed Feb 10, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/explorers/coronavirus-data-explorer.

Image Credits

- DHEC. “South Carolina County-Level Data for COVID-19.” South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control: Columbia, SC. Feb. 6, 2022. Accessed Feb. 9, 2022. https://scdhec.gov/covid19/covid-19-data/south-carolina-county-level-data-covid-19.

- DHEC. “South Carolina County-Level Data for COVID-19.” South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control: Columbia, SC. Feb. 6, 2022. Accessed Feb. 9, 2022. https://scdhec.gov/covid19/covid-19-data/south-carolina-county-level-data-covid-19. See “Deaths” tab.

- “Structural Racism.” Racial Equality Tools. 2020. Accessed online Feb. 2, 2022. https://www.racialequitytools.org/resources/fundamentals/core-concepts/structural-racism.